In the 19th century, the gender pact dividing public and private spheres, as man-owned and women-inhabited, found its most solid reasoning. The separation of the private and the public was accelerated by the Industrial Revolution when it fixed a role of the key “bread-winner” for the man. The gender-divided lines of responsibility certainly existed before the 19th century, but the role of women in family economy before the Industrial Revolution was much more visible. Since the Enlightenment era, the idea of the private and the public (as female and male, respectively) has been included in legal codes of most European states. This way, the new economic order was enshrined in the law, where the labor of those in charge of the private (women) was no longer considered significant, since it did not yield any profit. The new capitalist matrix unavoidably affected the role of a woman in space, framing it into the classic bourgeois ideal – Kinder, Küche, Kirche. This ideal was not identical with the actual practices, as it was distinctly attached to social class. Women originating from the unprivileged social strata found it more difficult to fit in, at least because they needed to “abandon home,” in other words, to earn their living.

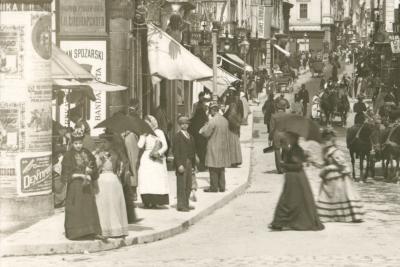

The city as the most obvious impersonation of the public sphere seemed to be male by default. According to sociologist Elizabeth Wilson, men own the city with no need to think about it, whereas women always need to consciously declare it every time, defending their right to be in the street [1]. Modern life was associated with competition, labor markets, and the daily need to fight for your “tomorrow” in a patriarchal society. These associations were discordant with the ideal visions about the homely female world.

In fin de siècle Lemberg/ Lwów /Lviv, city spaces for women were rather limited. Their phased expansion was caused by economic expediency (increasingly, more women migrated to cities in search for jobs) and by the emancipated ideas implemented in the expansion of female schools, societies, and the list of professions accessible to them, and thus new environments.

Women in the city were taken as potentially threatened. As Judith Walkowitz shows in the example of late Victorian London, on the mental map of urban dwellers women did not have the autonomy; they were the carriers of senses assigned to them by others rather than independent actors [2]. The list of bans for Galician women not only denied access to certain places such as universities before the end of the 1890s (the first female students entered Lviv University in 1897), but also to regular everyday experiences they could try only at the cost of their own reputation. Still in the early decades of the 20th century, it was considered normal for a young woman from the “intelligentsia family” to be accompanied by a chaperon, either a “mother, aunt, or a tutoress.” Julia Schneider (future Ukrainian poetess Uliana Kravchenko) recalled how scandalous her behavior was perceived by the Lviv public when she, as a young girl, went to the Ossolinski library by herself and met Ivan Franko, still unmarried at that time, either at coffee places or at the editorial office of the Dilo newspaper. Her meeting and a conversation with a man she knew, in the middle of the street, ended up with a scolding. She had to endure discussions wherein it was presented that the only logical solution to maintaining her reputation was for them to be married.

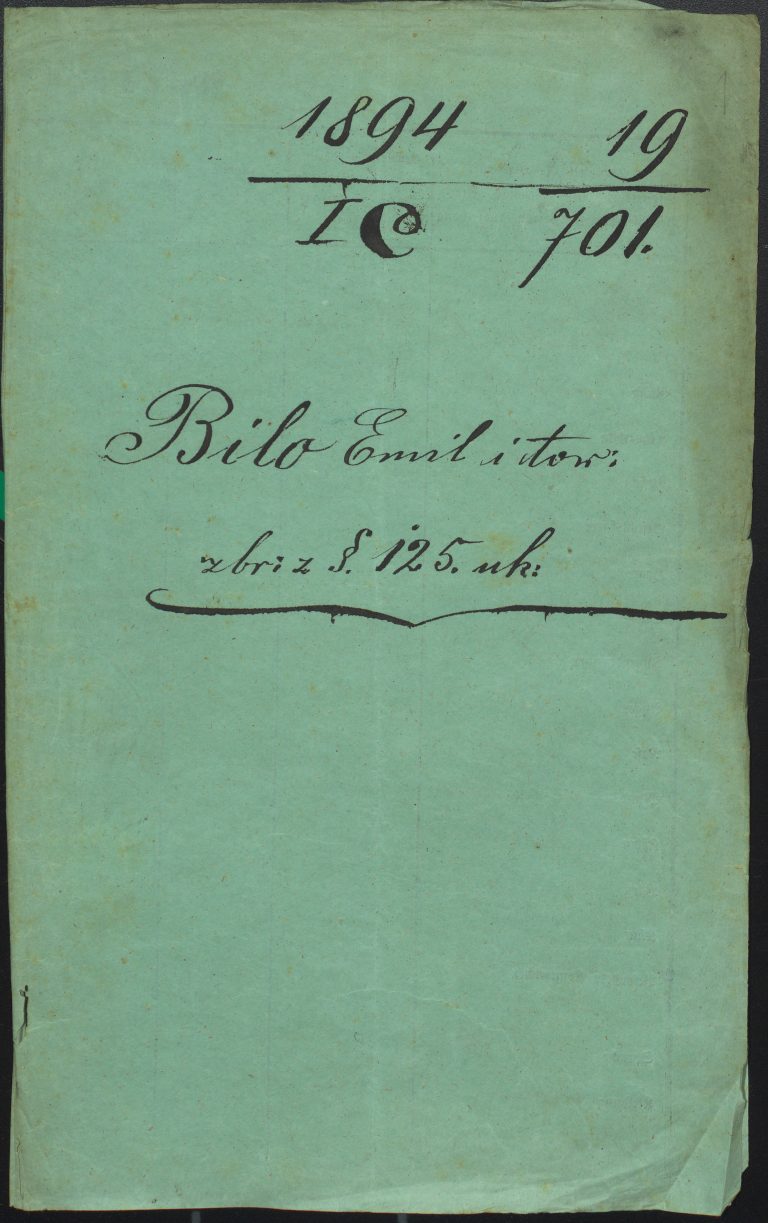

Poor women, because of their economic vulnerability and social subordination, risked descending into threatening situations. It can be vividly illustrated by rape cases. Female rape victims who found themselves in danger had to explain how they got there – for example, why had they stayed in the city street in the evening (see more: The Emil Bilo Rape Case, Lviv, 1894). After that, they could proceed with describing the attack. Since the law did not protect a woman’s personality but rather her dignity, the major burden of proof fell on the victim, on the raped woman who had to prove her honorable name.

The city as a source of threat to women was mostly associated with prostitution and sex trafficking. The position that young girls must be protected against falling into the “light conduct” and eventually into prostitution was the most popular topos in the public debate around this topic [3]. The city, and its numerous “temptations” such as stores, coffee-houses, candy shops, or dance floors, was presented to women from the poorest levels of the social ladder as especially risky. A popular public discourse referred to the need for their continuous protection and patronage, often against them themselves. One of the obvious motifs of such narratives said that the easiest way for poor women to reach the dream city life would be to do prostitution (in fact, the plan was to protect them against choosing this track). Moreover, the narrative implied that prostitution was treated as an easy earning or as a sign to avoid any work at all. The latter message was significantly undermined by feminists who claimed that the prerequisites for women to fall into the allegedly “easy” field (as prostitution was believed to be) came from their limited opportunities to earn their living otherwise, due to existing gender inequality in labor markets. After all, the official data also confirms it: among women enlisted into Lviv police records of prostitutes, most of them had another jobs, in addition to prostitution, such as housemaids, seamstresses, embroiderers, or “odd jobs” (see more: An article in the monthly “Świat Płciowy” about prostitution in Lviv, 1905).

The common media storyline about sexual slavery that the “innocent village girls” could fall into went approximately the same: a young girl would be maliciously tricked by a job offer and later ruthlessly sold for men’s pleasure; or she would be cynically tempted by marriage promises from disguised sex traders – the girl would believe it and run away from home only to end up in sexual slavery. “The fate that awaits them there – one of the Lviv newspapers was retelling the story – is obvious to everyone but the victims themselves” [4]. Women were presented as highly naïve, even gullible, and the city was rarely shown to them as a source of opportunities. In relation to the city, they were mostly victims, which, obviously, was not always true.

“Do you think I had to lie to them all and say that I needed them (girls – ICh) to serve in houses (as housemaids – ICh)? Dozens of them were saying directly: “Even if you sell me, Madam, to the Turkish slavery, we will bless you in any case if we get the chance to get out of here. For here, we only have an option of a desperate suicide or the road of disgrace, without even any guarantee that we would get in return the safeguard against poverty, starvation, and slavery!” – This is what Anelia from Ivan Franko’s novel “For the Home Hearth” (1892) was saying when she explained to her husband her evident crime of recruiting Galician girls for sex trafficking abroad. Ivan Franko chose prostitution as a background theme for his novel to appeal to the existing social injustice that concerned him as a socialist, and generally as the most famous Ukrainian of those times who publicly supported the women’s movement. Furthermore, the author also raised another uncomfortable question, either consciously or not: should a woman have a choice in how to use her body?

The public discourse of those times could not have any such discussions of course. That might be the reason why Franko struggled for a long time to publish that novel and had it rejected by publishers. Even more so that the topic was pertinent enough. At that time, Lviv was actively discussing at least several high-profile criminal cases related to sex traffickers [5]. Enjoying the bad fame in the empire as the second most “immoral” city (following Budapest), Lviv did not find the topic surprising as the urban society was accustomed to permanent scandals around it [6]. However, critics accused the author of being too indulgent about the protagonist, Anelia Anharowych, who was depicted with pity, or even worse, with understanding. The final scene must have diminished Franko’s authority in the eyes of moralizers, too. In that episode, the girls who were supposed to point to the perpetrator who sold them into sexual slavery did not do it, thus manifesting collective women solidarity: “How noble, almost holy, did the fallen girls seem to him at that moment, although so badly hurt by his wife, as in that hard time, they found in their hearts so much humane and selfless attitude and forgiveness to be able to say one simple word of “No” with so many heavy consequences otherwise” [7] (see more: For the Family Hearth, a 1970 film).

The link between work, sexuality, the stigma of a “potential whore,” and the risk of male violence towards city female workers built a dense mix of prejudice and stereotypes (see more: Anna Pavlyk Essay “Worker girl” Lviv, 1887). In the framework of social suspicions, housemaids had a special place. Connotations around serving as a maid implied low moral standards of women accepting such jobs, and also their possible sexual pliability. No supervision from the family members or lack of proper moral environment (obviously implied by their need to earn their own living) which each young person, especially woman, needed to have according to the social norms, caused suspicions about housemaids as less honest or virtuous by default. That could also explain the quite conscious attitude of the ladies of the house who would turn a blind eye to the fact of their adult sons running after the housemaids. They deemed it as acceptable, and moreover, as a quite “normal” sexual practice for men. The moral drama of consequences from such prejudice about women of her time was vividly illustrated by Gabriela Zapolska in a comedy drama “Morality of Mrs Dulska” (1907). The protagonist, Mrs Dulska, according to literary critics, was copied from the real person, a Lviv-based woman (according to one version) who was explaining on the pages of the popular Polish magazine “Wiek Nowy” her home order based on selfishness, greediness, and making use of servants. The play’s idea is that a village girl named Hanka was a main victim of Mrs Dulska’s disciplining methods. Her son made the maid pregnant as she planned to use the hired maid to satisfy the adolescent son’s sexual desire within the home.

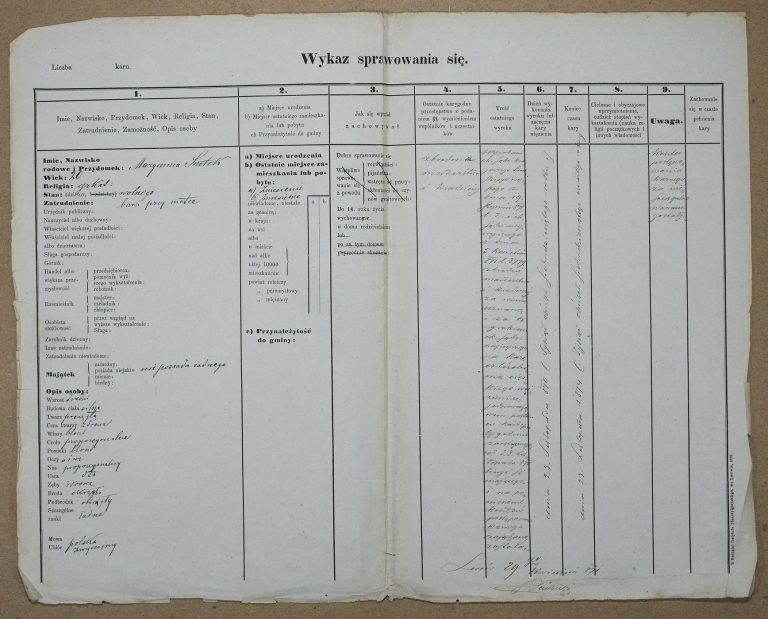

Children of urban female workers born out of wedlock became a very evident issue of city life by the end of the century. It was confirmed by the statistical increase in criminal cases on infanticide or child abandonment, and also by the frequency of reporting about such cases in the daily press. In fact, single working mothers shaped a need for a separate area of services for childcare, engaging women from suburban villages (see more: The Case of Maria Shutek on Infanticide, Lviv, 1870-1871). The problem of unwanted children and single mothers was understood as a moral wound of society in changes which followed the decadent attitude of the end of the belle epoque.