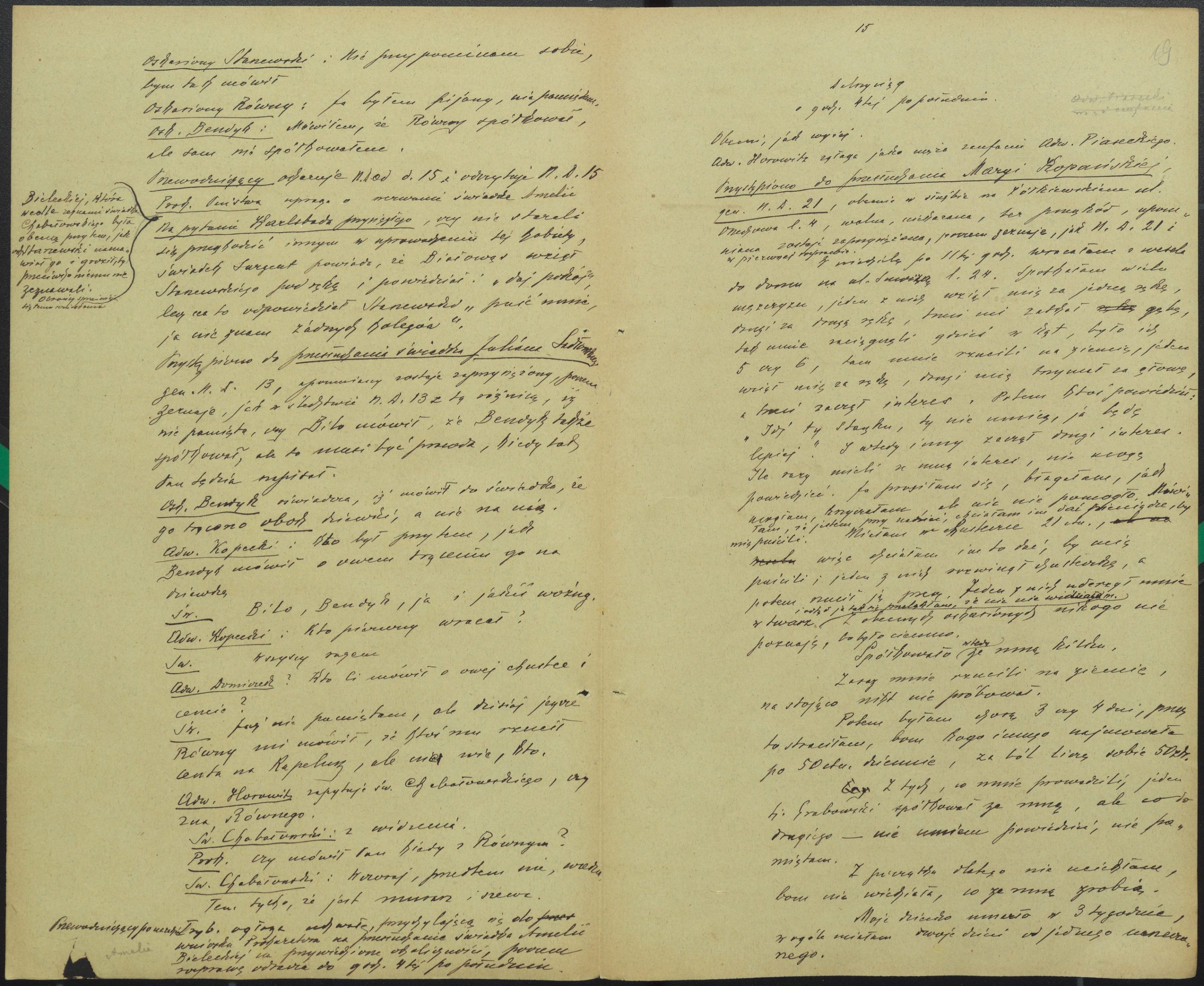

Continuation at 4 p.m.

Those present as above.

Att. Piańcki introduces Att. Horowitz as his trustee.

The interrogation of Maria Kopańska started (currently in service in Żółkiewskie [suburb], ul. Orzechowa 1/4, single, no record, no obstacles), who was sworn in and then testified as in the first hearing.

On Sunday after 11 p.m. I was returning home from a wedding held at ul. Śnieżna 1/24. I met many men, one of them took me by one hand, the other by the other hand, the third one put his hand over my mouth; they dragged me somewhere into a corner, there were 5 or 6 of them, they threw me on the ground, one took me by the hand, the other was holding my head and the third started making it. Then someone said, “Go away, Stanek, you can’t, I’ll be better.” And then another one started making it for the second time. How many times they did the do with me, I can’t say. I begged as much as I could, screamed, but nothing helped. I said I was in a delicate condition, I wanted to give them money to let me go. I had 21 cents in my handkerchief so I wanted to give it to them to let me go; one of them unfolded the handkerchief and then threw it away. One of them hit me in the face and I was so scared that I couldn’t see anything. I do not recognize any of the defendants present, because it was dark.

At that time, several men had intercourse with me; they immediately threw me on the ground, nobody tried to do it while standing.

Then I was sick for 3 or 4 days, which made me lose 50 cents, because I hired somebody else for 50 cents a day; for the pain, I charge 50 zlotys.

Of those who led me, a Grabowski had intercourse with me, but as for the other, I can’t say, I don’t remember.

I didn’t run away at first because I didn’t know what they would do with me.

My child died 3 weeks later, I had two children from one fiancé.

Prosecutor: How long did this incident last?

Witness: The whole event from the meeting up to going to police lasted for an hour.

Att. Horowitz: You were led far from the street.

Witness: I don’t know, they dragged me.

Att. Horowitz: Who strangled you?

Witness: I don’t remember.

To the relevant questions of Att. Horowitz she replied as follows: The two [men] led me, one threw me to the ground, then someone had intercourse with me, but I do not know whether it was the one who had led me; then someone said to the first one: “Go away, Stanek, you don’t know how” and the other started intercourse with me, and then someone hit me in the face, I don’t remember any more, but no one had intercourse with me again after that.

After mentioning that previously she had testified differently, she made a correction saying that she could not say that there were four or five of those having intercourse with her, rather two or three.

The last one who had intercourse with me was Haba. Whether he was on me after Stanek, I don’t remember.

![Image for The Morality of Mrs. Dulska, 2013 TV Movie [Moralność pani Dulskiej]](https://edu.lvivcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/moralnosc-pani-768x508.jpg)

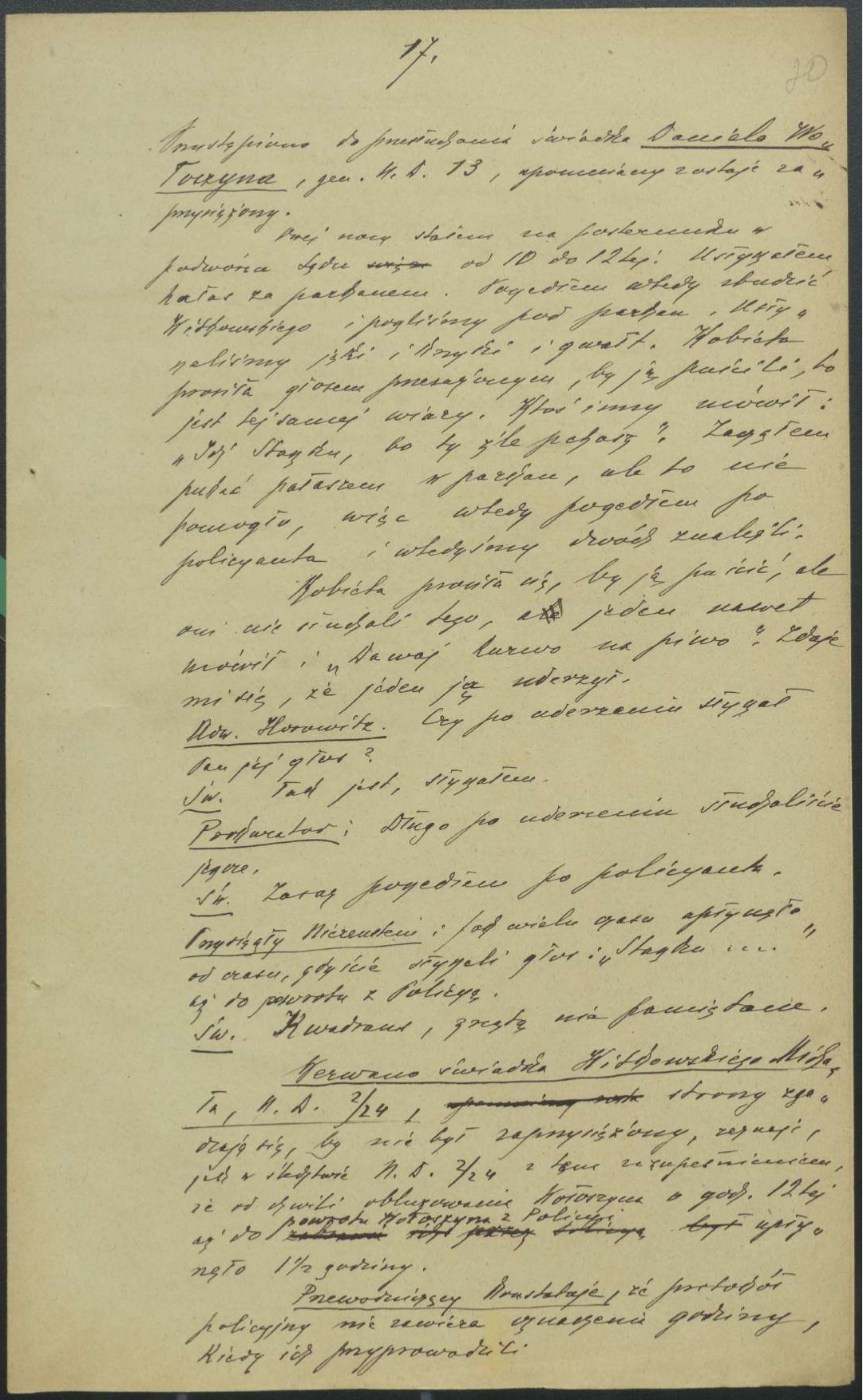

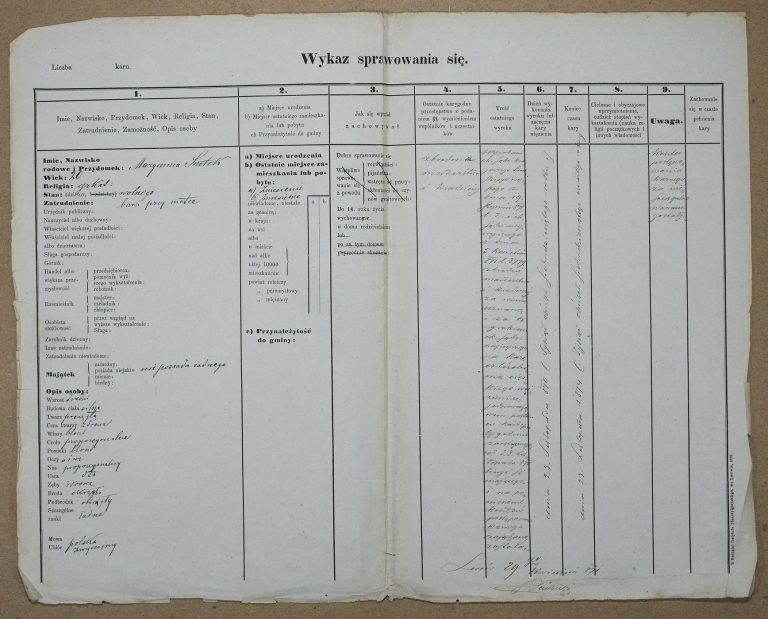

The submitted text is part of a criminal case considered by the Criminal Division of the Lviv Regional Court in 1894 against four men accused of raping a woman named Maria Kopanska. The selected fragment is the testimony of the plaintiff, as well as of a witness Danyil Voloshyn. The event occurred on September 10, 1893, at about 11 p.m. in the Zhovkva neighborhood of the city, near the Brygidka prison. The presented document shows the peculiar nature of the information the judges requested from the injured party. This information was supposed to confirm not only the fact that the offense had been committed against the woman but also to justify her right to act as a plaintiff. As evidenced by the acquittal, this information was not convincing for the judges. The testimony of a witness, Danyil Voloshyn, was not considered, either. The court decision exempted all three men from criminal liability, except for the fourth man, Emil Bilo. He was never brought to trial; he was in the wanted status. His name gave the court case the title to be included in the criminal chronicles.