Art

Studying art involves a variety of disciplines – from philosophical aesthetics, to the history of art, or even visual studies. Historical narratives connected to objects of art reflect the diversity of human experience and help us understand cultures, ideas, and traditions that are different from our own. Art history allows scholars to understand artworks as meaningful products of specific time periods and places, to realize how different our lived experience is from that of our predecessors, and yet, how little has changed with regards to our aspirations and values. This theme on our Educational Platform deals with phenomena of urban art and creative spaces (like workshops or galleries) – this includes spaces involved with fine art, other imagery, cinema, documentary or fictional narratives, and theater. Understanding our history through art helps us to make sense of the past and, by analyzing what is represented in the art itself, we can understand what was considered important and valuable. Stories about the lives of artists, their practices, artworks, how they interacted with their cities, and their navigation of society can inform our thinking about history and aesthetic comprehension. It can also help us to understand how our own lives fit into the human experience.

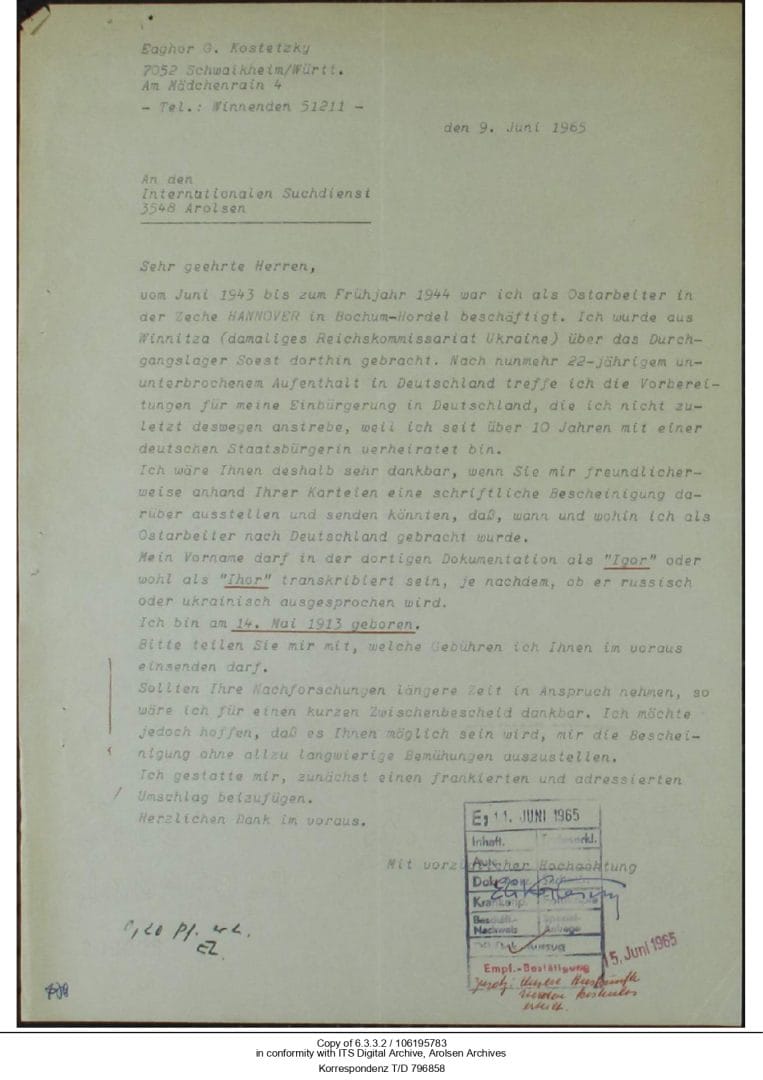

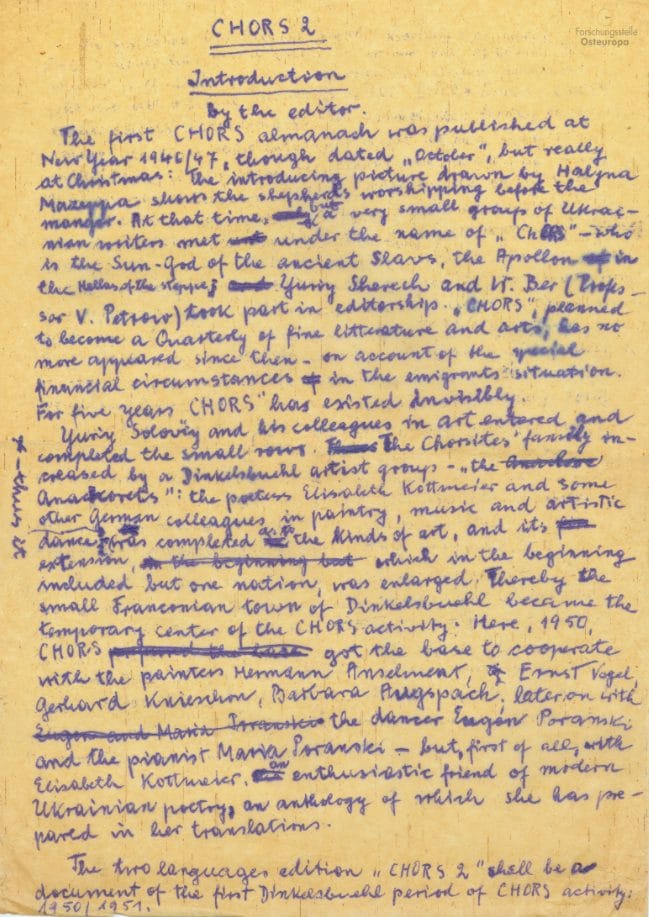

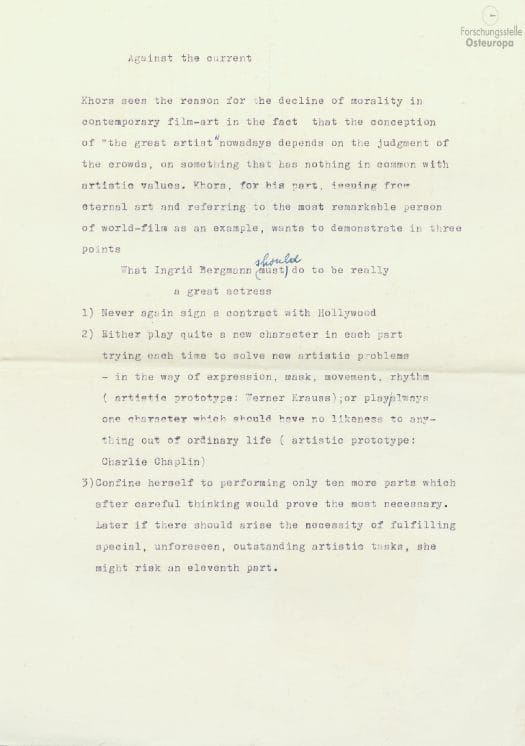

Primary Sources

Reflections