The early vision of amateur filmmaking in the Soviet Union was characterized by the pragmatic idea of using the new media not only for entertainment but also to involve a wide range of citizens in the production of newsreels and to create a network of correspondents across the country to cover the construction of socialism. However, despite sporadic attempts, this idea was not immediately implemented on a large scale. The lack of technology and sufficient equipment, and later the political climate of the 1930s, hindered this. It was only after liberalization and Khrushchev’s reforms that the idea reappeared on the agenda. Furthermore, producers of mass consumer goods, rather than highly specialized technological enterprises that could only produce small orders, took up the production of amateur film equipment [1]. Since the 1950s, the amateur film movement gained significant momentum in the USSR in general, and in Ukraine in particular.

The inception of amateur cinema in the Ukrainian SSR can be traced back to the establishment of the Society of Friends of Soviet Cinema (in Ukrainian, Товариство друзів радянського кіно, ТДРК). The first branch was founded in 1925 in Odesa, later replicated in other cities, mirroring the model set by Moscow and the RSFSR at large. The primary objective of the Society of Friends of Soviet Cinema was to advance the process of kinoficaciya (cinefication), a policy aimed at bolstering film infrastructure and education, particularly in rural and remote areas. According to its charter, the Friends of Soviet Cinema prioritized enhancing the reception of cinema, often intertwined with propaganda, among workers and peasants, with film production itself considered secondary [2]. The terms “film amateurs” or “film enthusiasts” primarily denoted individuals passionate about cinema, engaging in viewing and discussion rather than creation. The earliest documented amateur filmmaking endeavors were linked to the initiatives of this organization, notably through the Cinematographic Experimental Workshops (in Ukrainian, Кінематографічні експериментальні майстерні, КЕМ) in Kyiv, Odesa, and Kharkiv [3]. However, in the early 1930s, the Society of Friends of Soviet Cinema underwent reform and eventual dissolution as part of Stalin’s policy of centralizing the cultural industry. This involved the establishment of a network of “unions” structured around various creative domains [4].

For these reasons, the official amateur movement was effectively suspended for almost thirty years during the 1930s. In an essay on the history of Soviet amateur filmmaking published in 1985, the authors refer to the period that commenced in the 1950s as the “second birth.” [5] Particularly noteworthy is the year 1957, marked by the production of the first small gauge 16mm film cameras on a mass scale, the Kyiv-16S-2, manufactured in Kyiv. Subsequently, in the 1960s, mass production of 8mm equipment commenced. Furthermore, the legitimacy of amateur filmmaking was affirmed by the 1957 World Festival of Youth and Students in Moscow. The late 1950s witnessed the inception of systematic institutionalization of amateur filmmaking, which was integrated into a network of trade union organizations or local cultural departments. Concurrently, there was a surge in individual filmmaking practices facilitated by the increased availability of cameras [6].

The further evolution of amateur filmmaking practices unfolded along two distinct paths: individual and collective endeavors. Collectivity emerged as a defining feature of Soviet amateur filmmaking. Aligned with the prevailing ideologies of the era, it was seen as intrinsic to the “essence of Soviet society,” with activities like amateur cinema serving as “novel means of cultural, educational, and propaganda initiatives.” [7] Integral to this approach were cinema clubs and film studios established within houses of culture, enterprises, and institutions, spanning both urban and rural settings. Also, there emerged a platform for interaction among film enthusiasts, who participated in reviewing, competitions, and festivals at local, republican, all-Union and international levels. The pinnacle of success was achieved when a film, following selection in competitions, received the honor of being broadcasted on television.

Although the concept of amateur filmmaking was intended to serve as a form of leisure outside of professional duties, participation in film studios often translated into employment. Each role carried responsibilities in planning and reporting, with film scripts requiring approval prior to shooting. Adherence to the film production plan was essential to showcase success and validate the studio’s existence. Prestigious recognition as “people’s” studios was bestowed upon the top-performing studios, granting them access to additional funding. Thus, the paradox of the “professional film amateur” emerged, epitomizing individuals tasked with executing the original concept of the authorities – that the working populace desires to create films. Studio leaders often comprised genuine enthusiasts or individuals with formal film education. The latter frequently encountered barriers in realizing their potential within the film industry, as production hubs were typically concentrated in major metropolitan areas. They often exerted significant personal efforts to demonstrate collective achievements, as their job prospects hinged upon it. The official nature of this phenomenon manifested in the content of the films produced: authors and teams had to document their own enterprises, create films aligned with the prevailing political climate, or, at best, engage in self-censorship to ensure approval of their work.

An exemplary illustration of an active amateur film movement can be found in Mariupol (known as Zhdanov from 1948 to 1989), where numerous film studios were established within industrial enterprises alongside the Zhdanov City Club of Film Amateurs. During the 1960s, these studios collectively published a newsreel titled Pryazovian Screen (originally in Russian, Приазовский экран). Each studio contributed a distinct news story focusing on pertinent topics related to the life of the city or the industrial plant, culminating in an issue of the newsreel that was showcased in local cinemas prior to regular screenings. It is noteworthy that the heavy industry enterprises in Mariupol possessed considerable wealth and resources, enabling them to support the amateur film movement at an elevated standard. Mariupol studios employed the 35mm film format, a technology coveted even by professionals. Consequently, industrial themes prominently featured in the films produced by Mariupol residents [8].

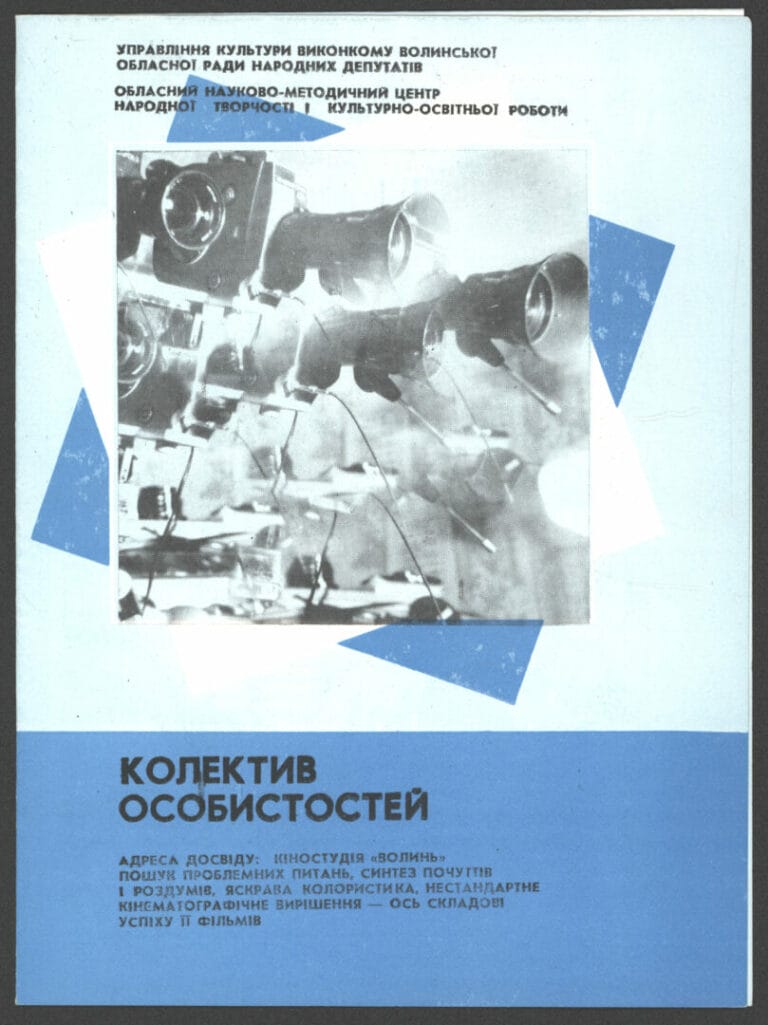

While large industrial enterprises maintained their own film studios and had the means to support them, local amateur clubs and studios operated within Houses of Culture in regions with less active economic development, receiving backing and funding from the Ministry of Culture [9]. For example, the Volyn studio in Lutsk (see “A Collective of Individuals.” Booklet of the Volyn Amateur Film Studio, 1987).

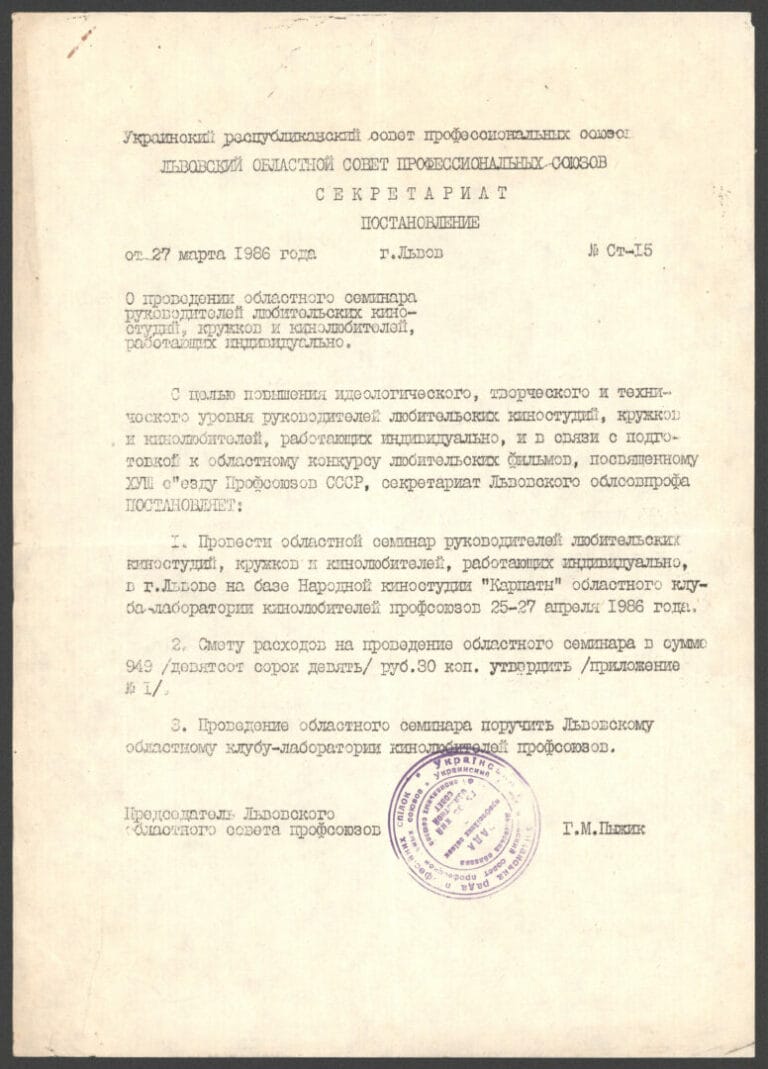

In Lviv, the Murator people’s film studio, under the leadership of Roman Buchko, operated within the House of Culture of Builders. It belonged to the network of trade union’s film clubs. The studio specialized in documentaries covering ethnographic, social, environmental, and historical subjects. Buchko, the studio’s director, was an enthusiastic advocate for amateur filmmaking. He organized amateur film festivals in Lviv during the late 1970s and early 1980s, as well as film clubs for schoolchildren, involving various organizations. Additionally, he established the Litopys studio at the kolhosp (collective farm) in the village of Zvenyhorod, near Lviv. According to the initial unofficial plan, the studio was meant to document archaeological excavations occurring in the area. To establish its formal existence, the initiator had to simulate full-fledged activity by attributing his earlier films to the studio and fabricating reports and participants who were purportedly co-authors [10]. This ruse enabled the studio to secure state funding. Thus, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the Litopys studio, comprising residents of Zvenyhorod, was established and began producing its own films. The formalization of activities, status, and integration into a broader network played a pivotal role in the amateur filmmaking process, as mere enthusiasm proved insufficient.

One rationale behind the predominance of documentaries in amateur film studios is that producing a feature film demanded considerable resources, skills, and training. In contrast, filming on location was more manageable, and sound films typically relied on narration and music. Additionally, amateur activities were intended to have practical significance, with films expected to resonate with a broad audience. It was believed that “ordinary workers” possessed a direct connection to their workplaces and could depict everyday reality authentically, a task often challenging for professional cameramen. Therefore, amateur filmmakers were tasked with ensuring that the camera delved into the deepest corners of social life, where direct Soviet propaganda might not reach, thereby promoting production discipline, order, and ideological engagement.

The decline of the amateur filmmaking phenomenon can be primarily attributed to the economic and political transformations that ensued following the collapse of the USSR. The crisis, transition to a market economy, and privatization of enterprises rendered financial support for creative pursuits and leisure activities impractical, particularly in low-profit sectors. Equally significant was the emergence of new technology during this period—video. As early as the 1980s, video technology was recognized as holding significant potential for amateurs, marking a new milestone in their development [11]. However, the advent of this new medium, coinciding with the spread of capitalism, fundamentally altered the landscape of interests and practices surrounding moving images. Throughout the 1990s, the amateur movement sustained some momentum, but gradually began to wane or undergo transformation in response to the evolving reality.

In the context of the Soviet project, amateur filmmaking emerged as a component of a revolutionary vision that viewed cinema as a technology for achieving political objectives as early as the 1920s. However, the widespread implementation of this concept only materialized at the onset of the 1950s and 1960s, when technical support for the mass amateur movement became feasible through the production of film equipment and materials. Given that amateur filmmaking served as yet another propaganda tool for the authorities, it was imperative for them to portray this phenomenon as a collective practice. Conversely, in capitalist countries, amateur filmmaking was often perceived as an individualistic and consumerist pursuit. The hierarchical organization of this movement within the Soviet state facilitated the proliferation of film studios and clubs, yet they depended on funding and the prevailing political climate. Despite the expectation for amateurs to produce propaganda films and uphold the official discourse, the available material resources allowed for avenues of creative expression. In such circumstances, understanding and intuition regarding the boundaries of permissibility were crucial. The personal commitment and enthusiasm of filmmakers remained paramount, often serving as a determining factor for the movement’s existence. Soviet amateur filmmaking emerged as a distinct arena for social and creative interaction through visual media, with the produced films serving as artifacts documenting the nuances of communication, mass culture, and politics of the era.

Literature:

[1] Vinogradova, M. (2016). Socialist Movie Making vs. Gosplan: Establishing an Infrastructure for the Soviet Amateur Cinema [Socialistická Filmová Tvorba vs. Gosplan: Budování Infrastruktury Sovětského Amatérského Filmu]. Iluminace 28(2), 20.

[2] Myslavskyi, V. (2017). The Society of Friends of Soviet Cinema in Ukraine in the 1920s [Товариство друзів радянського кіно в Україні в 1920х роках]. European Philosophical and Historical Discourse 3(3), 84-85.

[3] Ibid, 88-89.

[4] Vinogradova, 11-15.

[5] Ilichev, S., Nashchekin, B. (1986). Amateur cinema: origins and prospects [Кинолюбительство: истоки и перспективы]. Moscow: Iskustvo, 15.

[6] Vinogradova, 20.

[7] Ilichev and Nashchekin, 16.

[8] Bagachenko, Anna. (14 September, 2021) “Супутник великого сінематографа [A companion to great cinema].” mrpl city.

[9] Interview with Roman Buchko. (1 November 2012). Urban Media Archive at the Centre for Urban History.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ilichev and Nashchekin,16.