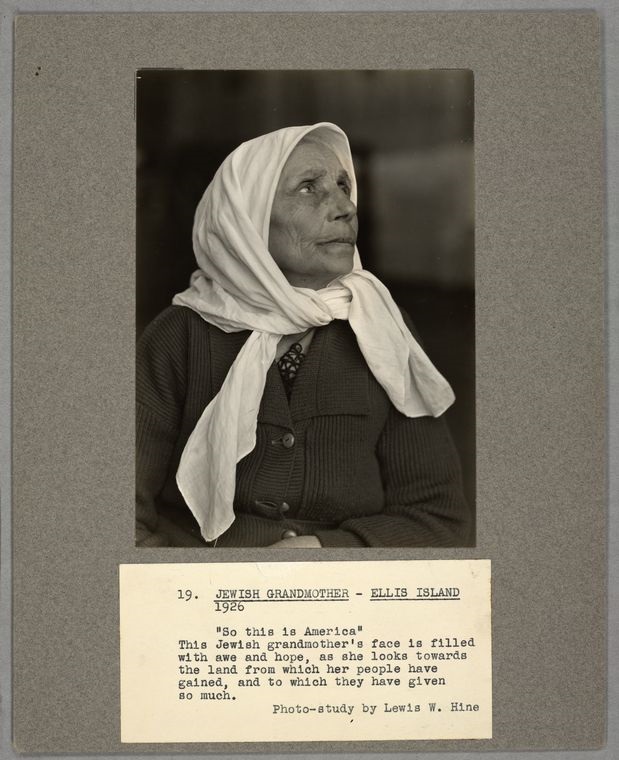

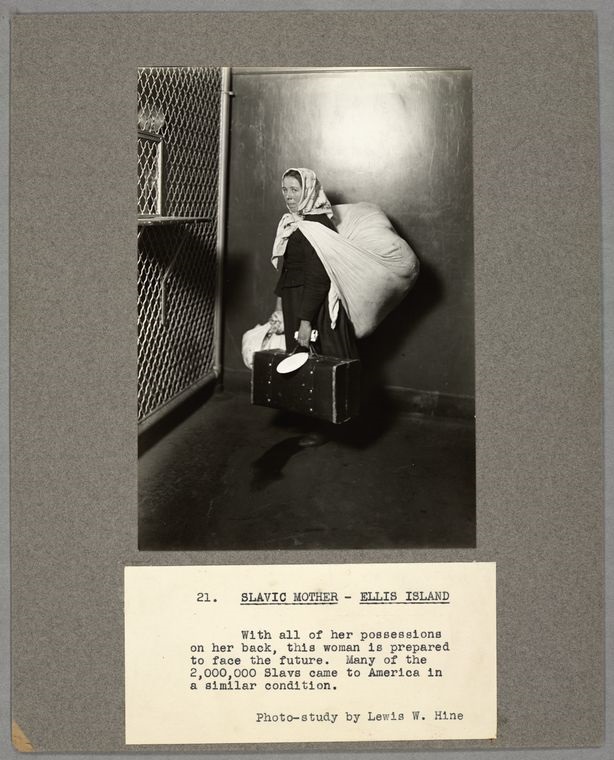

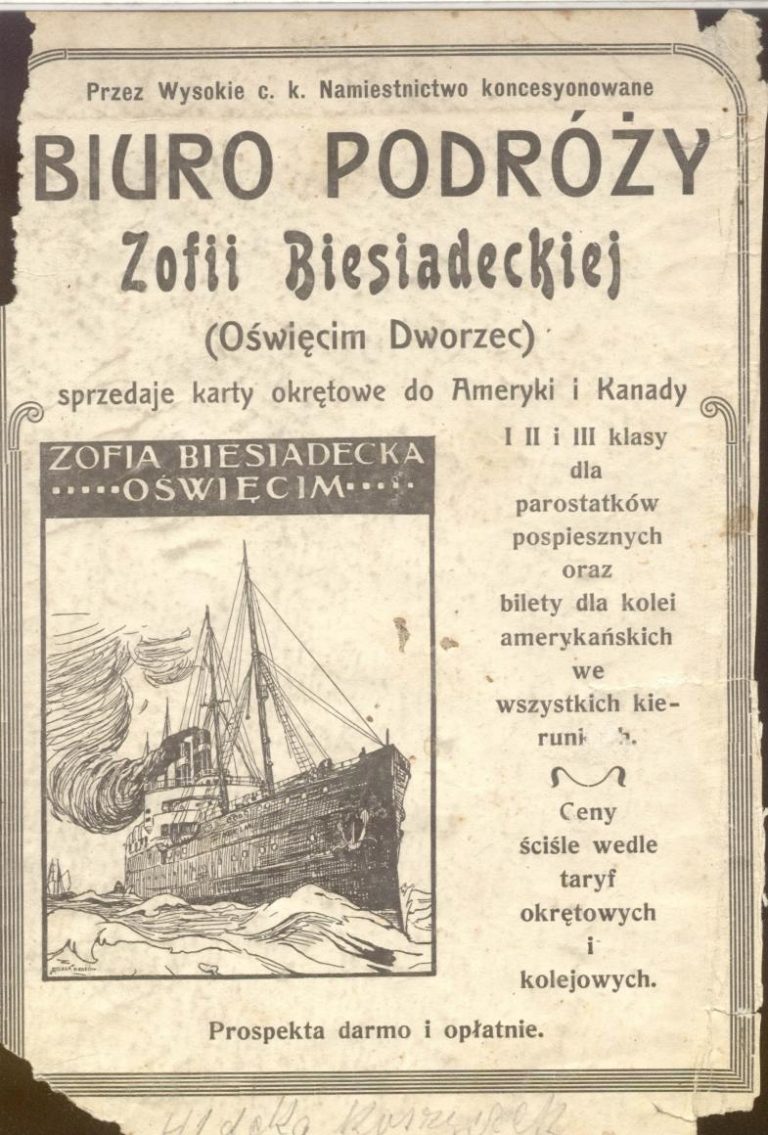

The end of the 19th century through the beginning of the 20th century is known as the period of mass migration from Europe to other continents, when more than 55 million people changed their place of residence. In particular, this process captured the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires, where a difficult economic situation, job shortages, and persecutions stirred various groups of the population to leave. Such groups included both Ukrainian and Polish peasants, and Jews from urban centers who were small-scale craftsmen or workers. Most often, they moved to the United States, Canada, Argentina, and Brazil, where labor was needed at factories or farms. At the turn of the century, the mechanisms of mass migration attracted people in different roles, as participants or organizers. Next to the legal labor market, there was an illegal market for human trafficking. In particular, the intercontinental trafficking of women reached an unprecedented scale, which became one of the most burning social problems in Eastern Europe. Migration impacted societies in the countries of origin, and in the countries of destination. People from villages or towns in Europe often faced new conditions and lifestyles, either in large industrial cities or when cultivating land under new harsh conditions. Mass migration did not necessarily mean a one-way ticket. Often, families, such as peasants, sent one of the adult children to the United States or Canada in order to improve their financial situation thanks to the money they sent back. Sometimes, migrants considered work abroad a temporary way to earn money, and returned to their native places, bringing new capital and skills. However, politicians were concerned about the outflow and rapid adaptation of young people in the United States and Canada. In fact, they could be involved in the development of the future state. Socialist movements in the United States and Canada tried to attract new migrants to their activities.

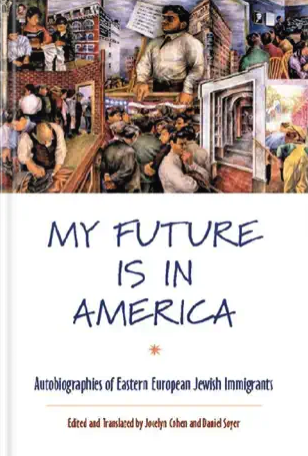

Sources that testify to the Great Migration at the turn of the century are quite diverse and include autobiographical writing (ego-documents), letters, works of art, remnants of material culture, and visual materials. The phenomenon of migration caused interest and concern among public and political figures, therefore, it was actively discussed in the printed media. Although the sources were created in the environments of the respective diasporas, common motifs, themes, and contexts of creation make it possible to consider texts in different languages together.

The process of integrating migrants into a new environment often contributed to the creation of a hybrid culture that combined their old experiences with new ones. Migrants created songs, short jokes, and stories. The hybridity of migrant culture was primarily manifested in the language, because migrants’ native languages – Ukrainian, Polish, and Yiddish– were receiving English words. Migrant folklore was a temporary phenomenon, as it arose among the first generation of migrants. For their children and grandchildren, integrated into new realities, it became less relevant. Characteristically, the works also migrated with their carriers between continents, returning to their family places or moving from the diaspora to the diaspora.

A selection of songs included in this module presents Ukrainian, Jewish, and Polish migrant songs collected in the 1950s – 1970s in the U.S. and Canada. Some of them have known authors, in particular, Yiddish songs were performed in theatrical productions. Some migrant songs in Ukrainian were collected in the diaspora or in Ukraine as folklore, and their authors are not known to us. Written in different languages, these songs reveal the similarities of shared experiences in America. The common motive is the naivety of the “greens”, i.e. the new emigrants, who had high expectations and did not know how to adapt. Often, the conflict in the songs is based on disappointment about the promised “golden land” which does not bring enough money or exhausts workers. Another common theme is about divided families. Often, in the case of long-term migration, one family member left first, taking the others along later. In the case of Jews, the lack of contact with men who emigrated exacerbated the precedent of the agunahs – women whose status remained uncertain because they were neither widows nor divorced. Quite often, migrants in new countries were attracted to the labor movement; they became active participants in demonstrations or strikes, which is also reflected in the texts. Jewish, Ukrainian, or Polish migrants could often have different directions of migration. While Jews worked in clothing factories or sweatshops in big cities like New York, Ukrainian workers were employed in mines or at farms, and the context of creating the texts is different.