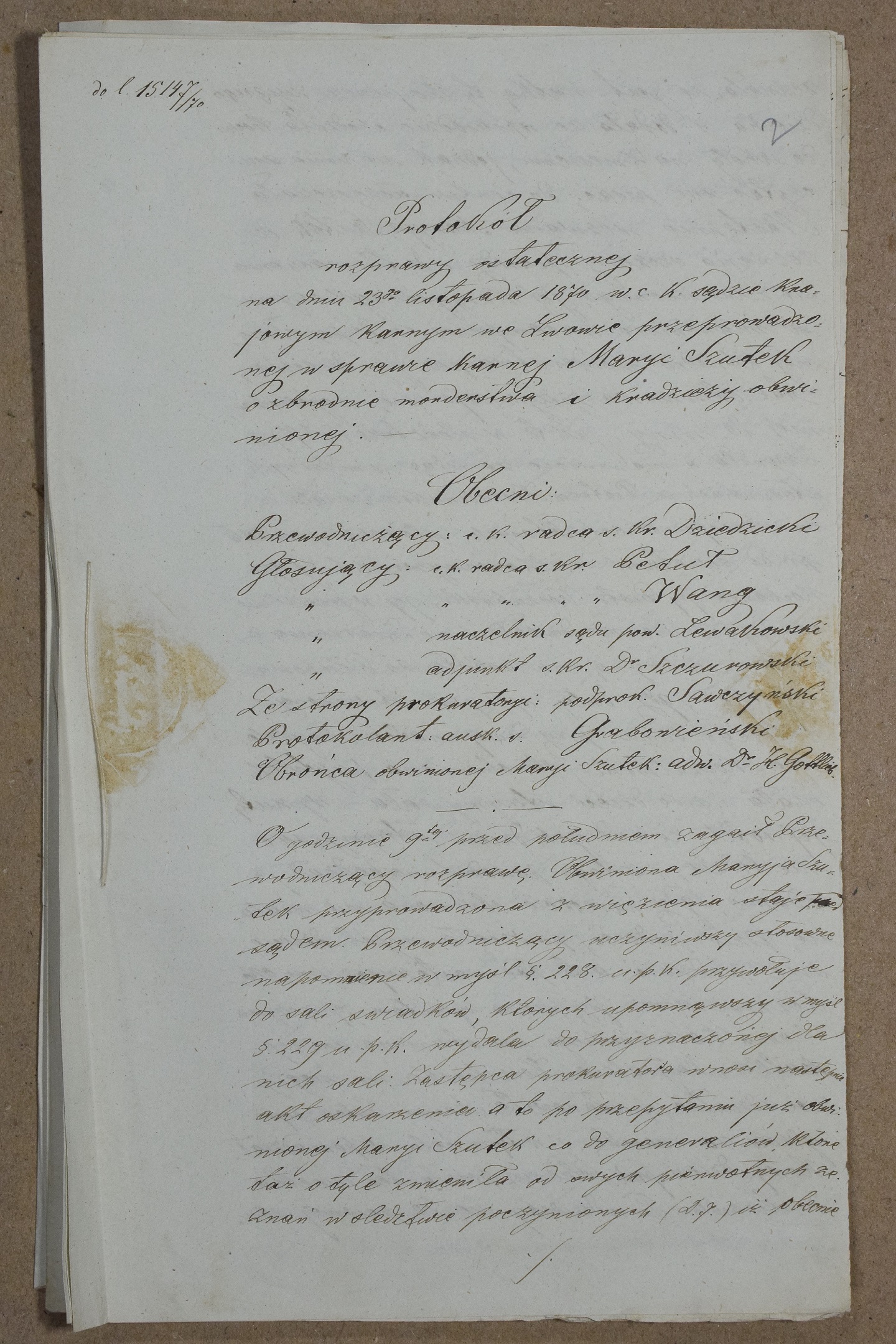

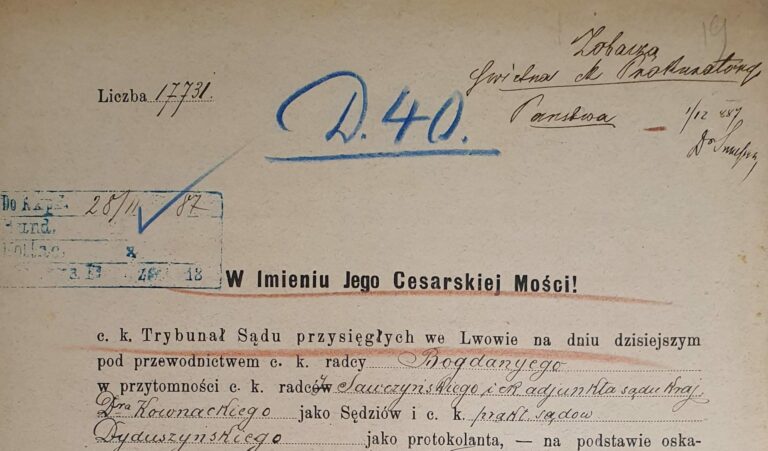

Minutes of the Final Hearing

23 November 1870

Regional Criminal Court, Lviv

Criminal Case Against Maria Shutek: Murder and Theft

Present:

Presiding Judge: adviser Dziedzicki

Voting Judges: adviser Petuł

«» «» «» Wang

«» Chairman of the District Court Lewakowski

«» Adjunct Judge Dr. Szczurowski

Prosecutor’s Office Representative: Deputy Prosecutor Sawczyński

Protocol Officer: S. Grabonzenski

Defence Counsel for Maria Shutek: Dr. H. Gottlieb

Proceedings:

At 9 a.m., the presiding judge opened the hearing. The accused, Maria Shutek, was brought from prison to stand before the court. The presiding judge issued a formal warning in accordance with §228 of the Code of Criminal Procedure and called the witnesses into the courtroom, ensuring they were duly cautioned per §229 of the same code.

The deputy prosecutor presented the indictment, questioning the accused, Maria Shutek, regarding the changes in her testimony compared to her earlier statements during the investigation (D.7.). The accused now stated that she was the mother of only one living child. She admitted that, although she had attended school in Znesenie for a short time, she was unable to read or write. She also mentioned her regular attendance at church.

When asked to explain the crime of which she stood accused—the murder of her child—Maria Shutek pleaded guilty. She recounted her version of the events, consistent with her investigation testimony (D.7.), and provided the following account:

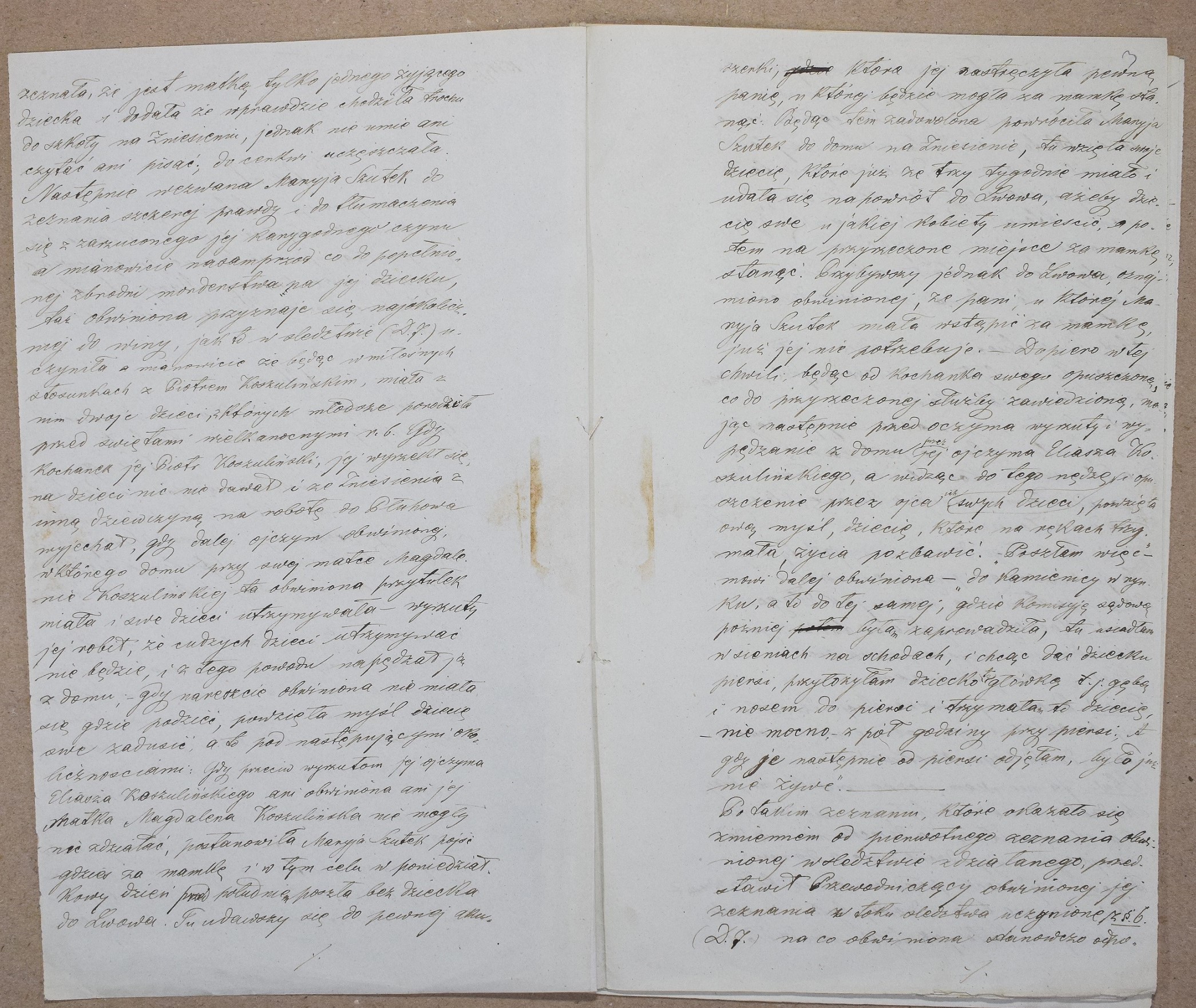

While in a romantic relationship with Petro Koshulinskyi, she bore him two children, the youngest of whom was born shortly before Easter of that year. After Koshulinskyi abandoned her, providing no support for the children and leaving Znesenie with another woman to work in Pluhiv, Maria sought refuge in the home of her stepfather, Eliasz Koszulinskyi, where her mother, Magdalena Koszulinska, and her children were also staying. However, her stepfather reproached her for being unable to provide for her children and eventually expelled her from the house. Desperate and with no place to go, Maria contemplated strangling her child as neither the defendant nor Magdalena Koszulinska could do anything against the reproaches of her stepfather. Alone, she went to Lviv on a Monday to seek a job of a wet nurse. In Lviv, she contacted a midwife who introduced her to a woman willing to employ her as a nurse. Encouraged, Maria returned to Znesenie, collected her three-week-old baby, and traveled back to Lviv to leave her child with some woman and begin her new job. However, upon her arrival, she learned that the woman no longer required her services. At this moment—abandoned by her lover, rejected by her stepfather, and unable to secure a future for herself or her children—Maria resolved to take the life of her child. She continued her testimony: “I went to a house near the market, the same one where I later took the court commission. I sat down in the corridor on the stairs. While trying to breastfeed my child, I placed his mouth and nose against my chest and held him—not firmly—for about half an hour. When I finally pulled him away, he was already lifeless.”

The presiding judge then presented Maria Shutek with her initial investigation testimony (§6, D.7.), which differed from her current account. Maria strongly insisted that her current testimony was accurate and clarified that her earlier statements lacked detail. Therefore, I emphasize that the idea of strangling her child occurred only after she learned that the lady she was to work for changed her mind.

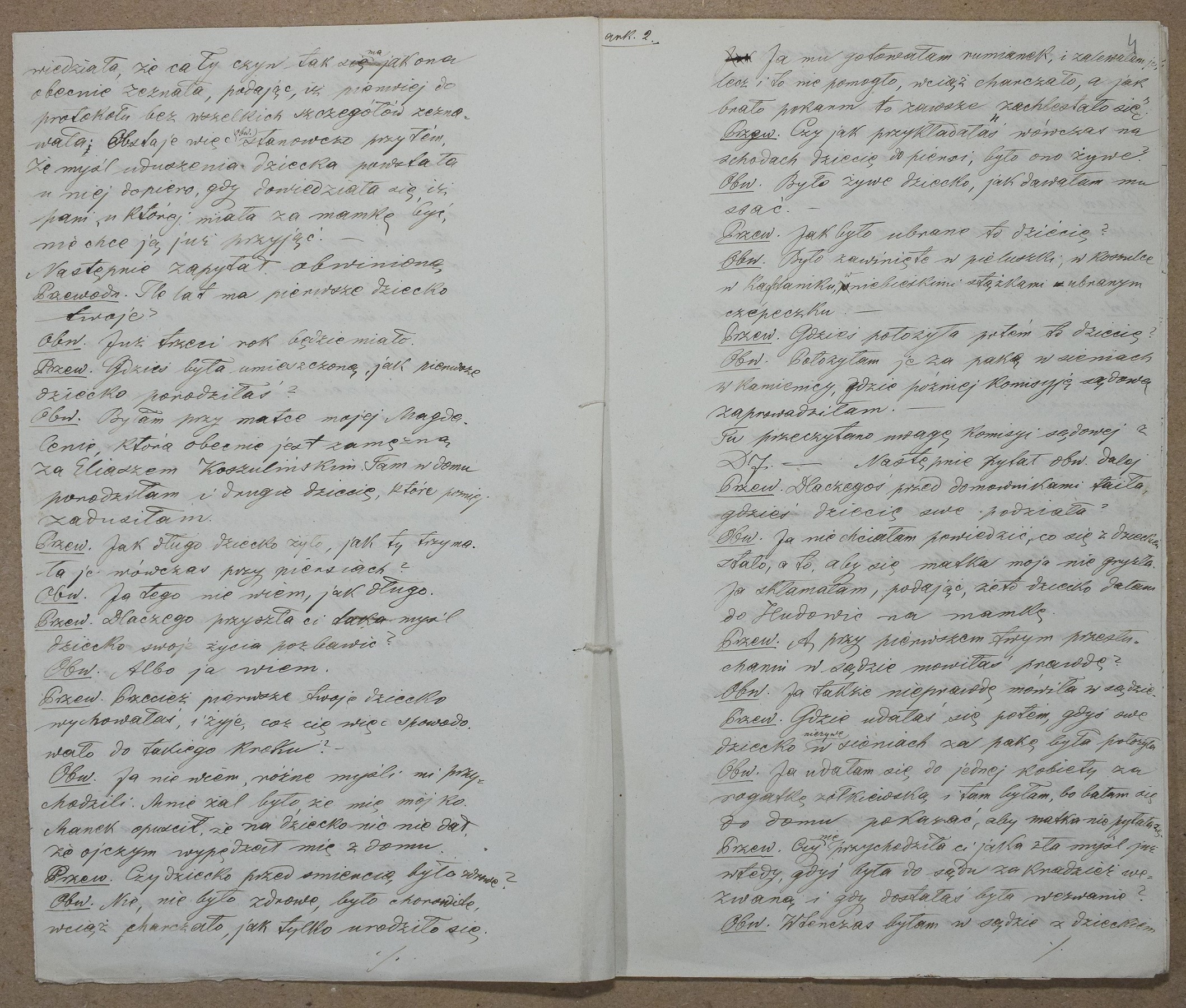

Then the accused was asked

Presiding Judge: How old is your first child?

The Accused: She will soon be three years old.

Presiding Judge: Where were you when you gave birth to your first child?

The Accused: I was with my mother, Magdalena, who is now married to Eliasz Koshulinskyi. I gave birth to my second child at home, the one I later strangled.

Presiding Judge: How long did the child live when you put it to your breast?

The Accused: I do not know.

Presiding Judge: Why did you decide to take your child’s life?

The Accused: I don’t know.

Presiding Judge: You raised your first child, who is still alive. What led you to take this step with your second child?

The Accused: I don’t know. Different thoughts came to me. I was upset that my lover left me, gave me nothing for the child, and that my stepfather kicked me out of the house.

Presiding Judge: Was the child healthy before she died?

The Accused: No, she wasn’t healthy. She was frail and wheezed constantly from the moment she was born. When I boiled chamomile tea and gave it to her, it didn’t help. She kept wheezing, and she always choked when she ate.

Presiding Judge: When you put the child to your breast on the stairs, was the child alive?

The Accused: Yes, the child was alive when I let her suckle.

Presiding Judge: How was the child dressed?

The Accused: She was wrapped in swaddling clothes, wearing a blue-stitched kaftan shirt and a cap.

Presiding Judge: Where did you leave the child after that?

The Accused: I placed her behind a box in the stairwell of the house, the same place where I later led the commission.

Here the remarks of the commission taken from D. 7 were read. Then the accused was asked further

Presiding Judge: Why did you hide from your family what had happened to your child?

The Accused: I didn’t want to tell them what happened, so my mother wouldn’t worry. I lied and said I had given the child to a nurse in Hodovica.

Presiding Judge: Did you tell the truth at the first trial?

The Accused: I also lied in court.

Presiding Judge: Where did you go after leaving your lifeless child behind the box?

The Accused: I went to a woman in Zhovkva and stayed there because I was afraid to go home, so my mother wouldn’t question me.

Presiding Judge: When you were summoned to court for theft and received the summons, did you have any bad thoughts about your child?

The Accused: I was in court with my child at that time, but they didn’t let me in because I had forgotten the summons at home. They refused to admit me without it. I was nervous then, everyone was nervous, and I didn’t know what to do.

Presiding Judge: Back when you were summoned for theft, had you already thought about getting rid of your child?

The Accused: This theft came to my mind when I wanted to strangle my child, because Petro Koshulinskyi told me he would have me imprisoned for three years for the theft.

Presiding Judge: At the first court hearing, you said you had two children.

The Accused: I had two children. When I gave my testimony, I forgot to mention whether my second child was alive, as no one asked me.

After the accused was presented with §. 4. with D. 7. The accused now confirms the same.

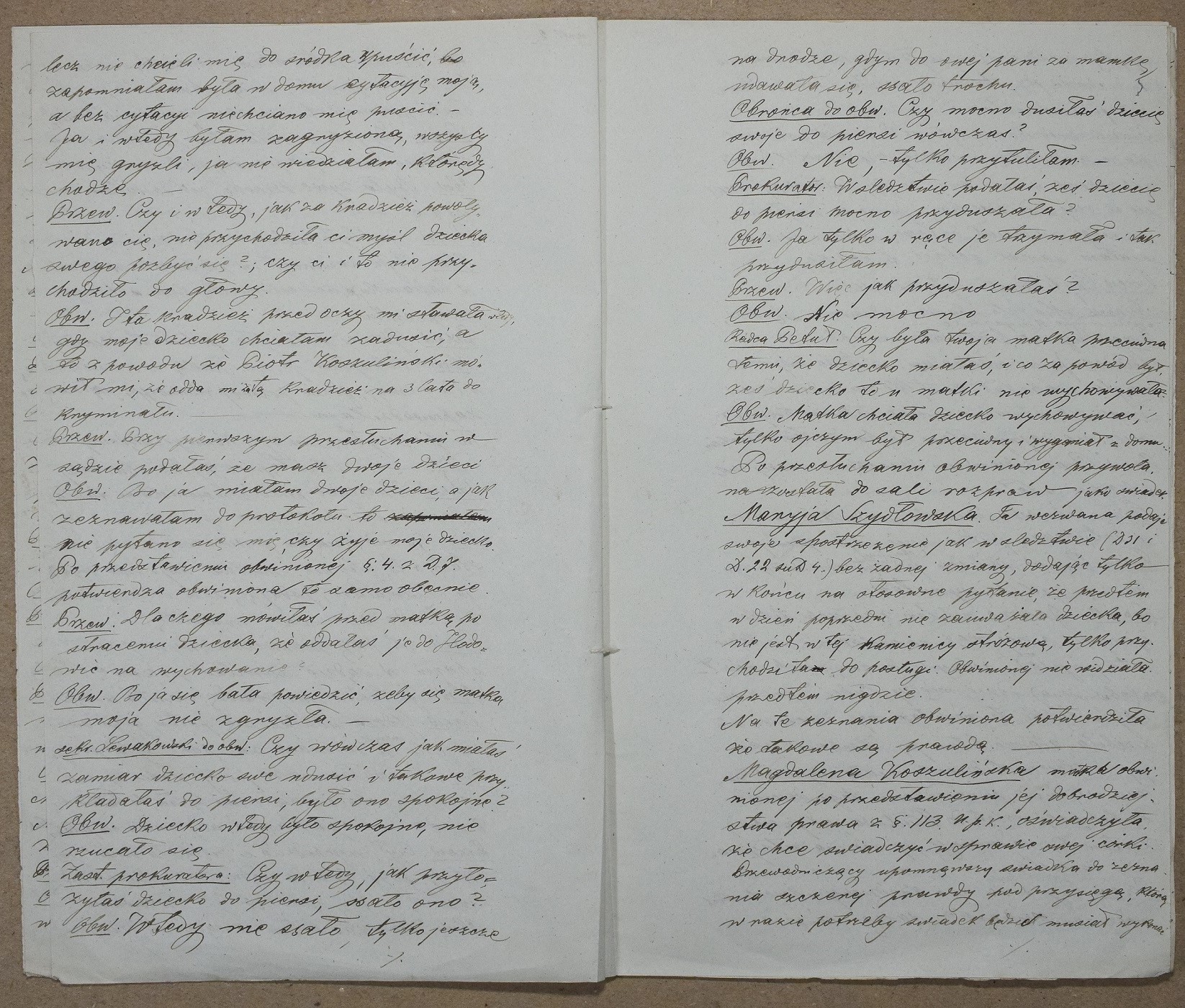

Presiding Judge: Why did you tell your mother you had given the child to Hodovica when you had not?

The Accused: I was afraid to tell her the truth, so she wouldn’t get angry.

Sec. Lewakowskyi to the Prosecution: When you decided to strangle the child and put her to your breast, was she calm?

The Accused: Yes, the child was calm at that moment and didn’t move.

Deputy Prosecutor: When you put the child to your breast, did she suckle?

The Accused: No, she didn’t suckle then. She only suckled a little on the way to the woman who was supposed to take her.

Defense Counsel: Did you use much force to smother your child?

The Accused: No, I just held her close.

Prosecutor: During the investigation, you said you held the child tightly to your chest.

The Accused: I only held her in my arms, and that’s how she suffocated.

Presiding Officer: How exactly did you strangle her?

The Accused: Not firmly.

Counsel Petul: Was your mother against you keeping the child? Why didn’t you raise her with your mother?

The Accused: My mother wanted to raise the child, but my stepfather was against it and kicked me out of the house.

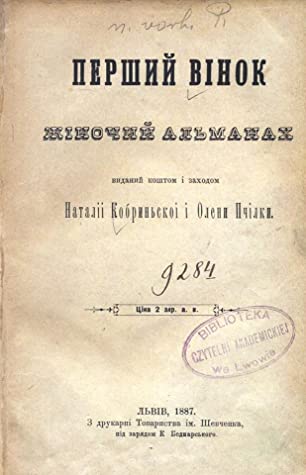

This text presents a fragment of Maria Shutek’s interrogation in her 1870 infanticide trial, where she was accused by the Lviv Regional Court. In her testimony, she provides her account of the crime and the circumstances leading up to it. The detailed autobiographical statement required from defendants for investigative purposes not only sheds light on the crime but also offers a window into Shutek’s life. Though such accounts were written more out of compulsion than voluntary reflection, the autobiographical narratives of criminal cases paradoxically offer a more balanced representation than traditional autobiographies. This is because they were cross-referenced and corrected by the testimonies of others during their creation. For legal purposes, these narratives were subjected to scrutiny, refutation, or corroboration through various supporting documents, including statements from community authorities about the accused’s social status (so-called evidence of estate), moral assessments from the parish priest (evidence of morality), witness testimonies, medical reports, records, private correspondence (if available), and physical evidence. The voices from the margins, preserved in criminal records, often provide the only means for women from the lowest strata of 19th-century society — many of whom were illiterate and historically “mute”— to share their stories.