Glory be to God in the ages to come, my dear[1].

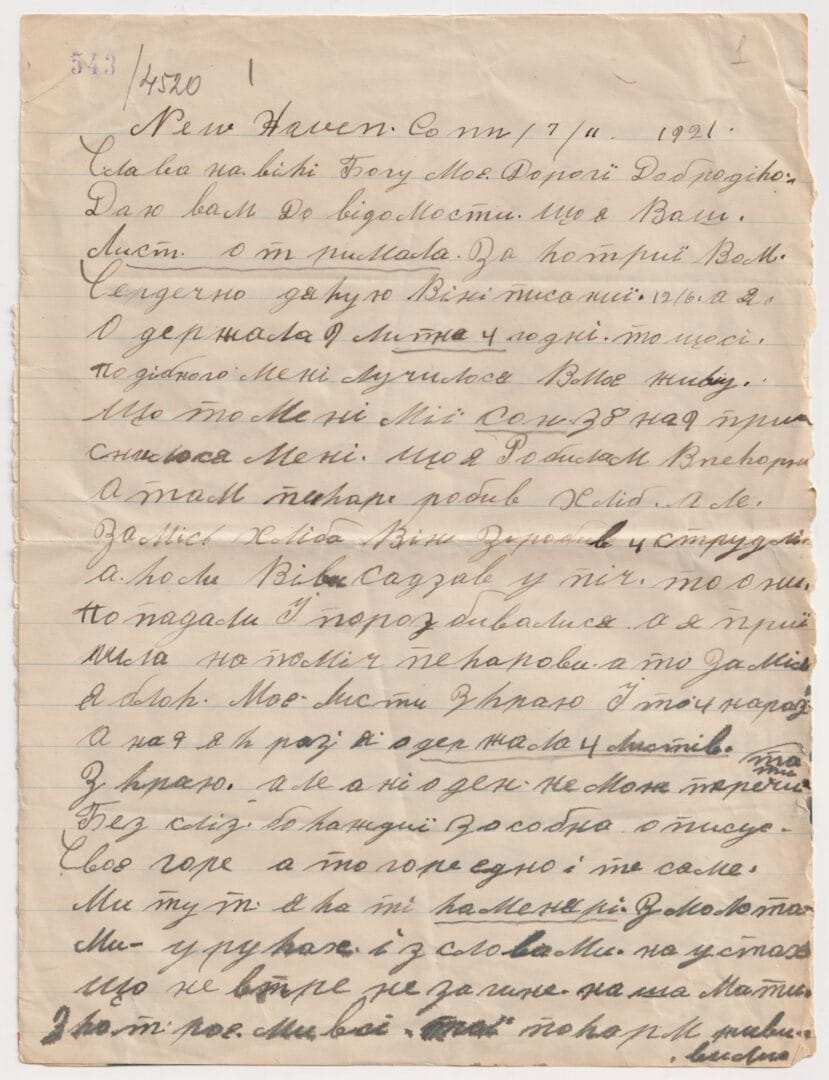

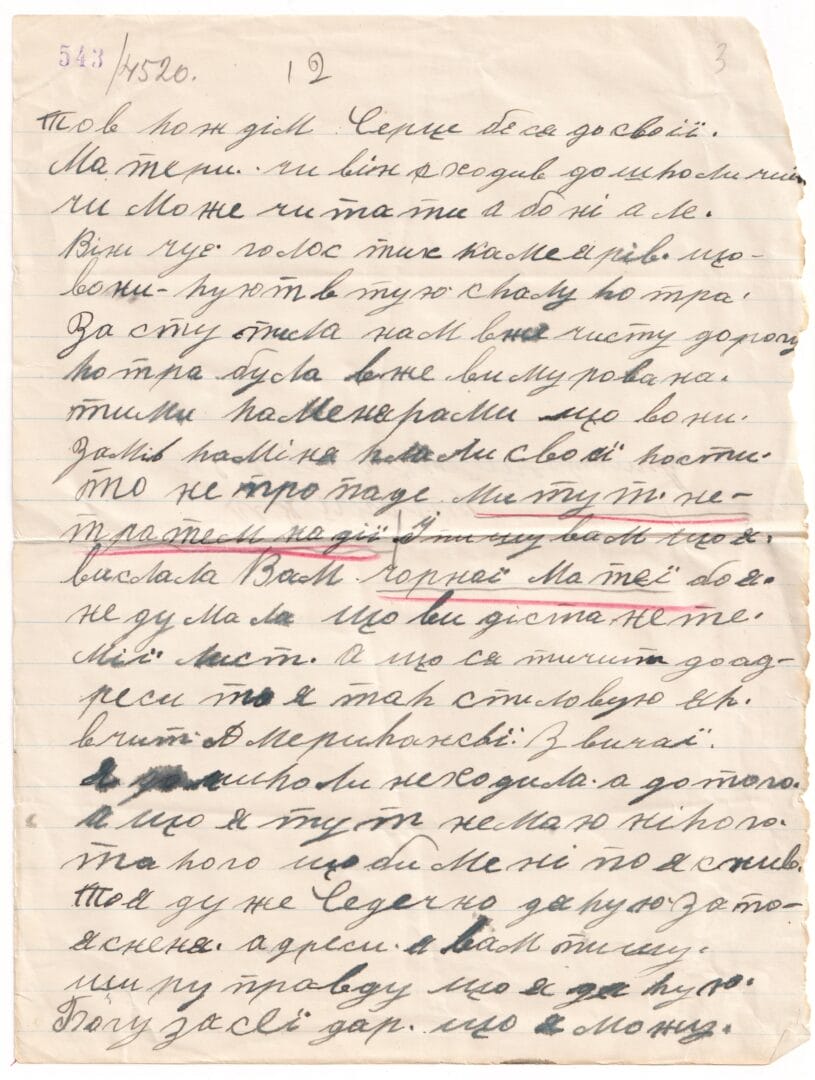

I would like to inform you. that I have received your letter. For which I thank you very much. It was written on 12/6 and I received it on 9 July [at] 4 o’clock. Something similar has been happening to me in my life. I dreamt about my drem on the night from 8 to 9. I was workin in a bakery and a baker was makin bread. But instead of bread, he made four strudels and when he put them in the oven. they fell and broke. And I came to the baker’s help. and see, it wasn’t about the buns, but about the letters from my homeland. And at the same time. On the 9th I received four letters from my homeland. Can’t read any without tears. Because each describes its own grief, and all grief is one and the same. We are like those masons here. With hammers in our hands and words on our lips that our Mother, from whom we have all been fed, will not die or perish. Each heart beats for their Mother. He went to school or not, he can read or not, but he hears the voice of those masons, that they are forging the rock that blocked the clear road paved by those masons before. They put their bones instead of stones. It won’t be lost. We are hopeful here. And I am writing to you that I sent you black closth because I didn’t think you would get my letter. As for the address, I’m writing it as Americen customs teach. I didn’t go to see Mykola. And I have no one here to explain, so thank you for explaining the address. I am writin you the sincere truth that I thank God for this gift [literacy – ICh]. That I can express my thoughts to myself. There is nothing worse in the world than to live in darkness. And for me too, because I live in a foreign land.

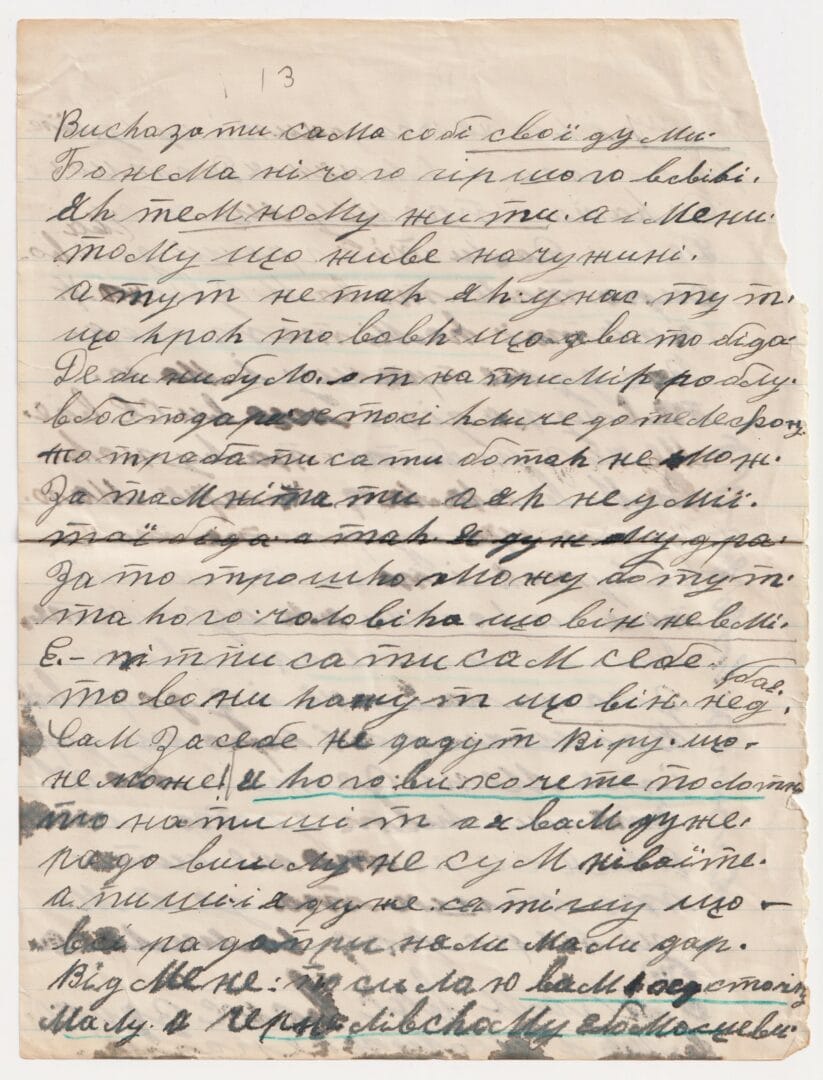

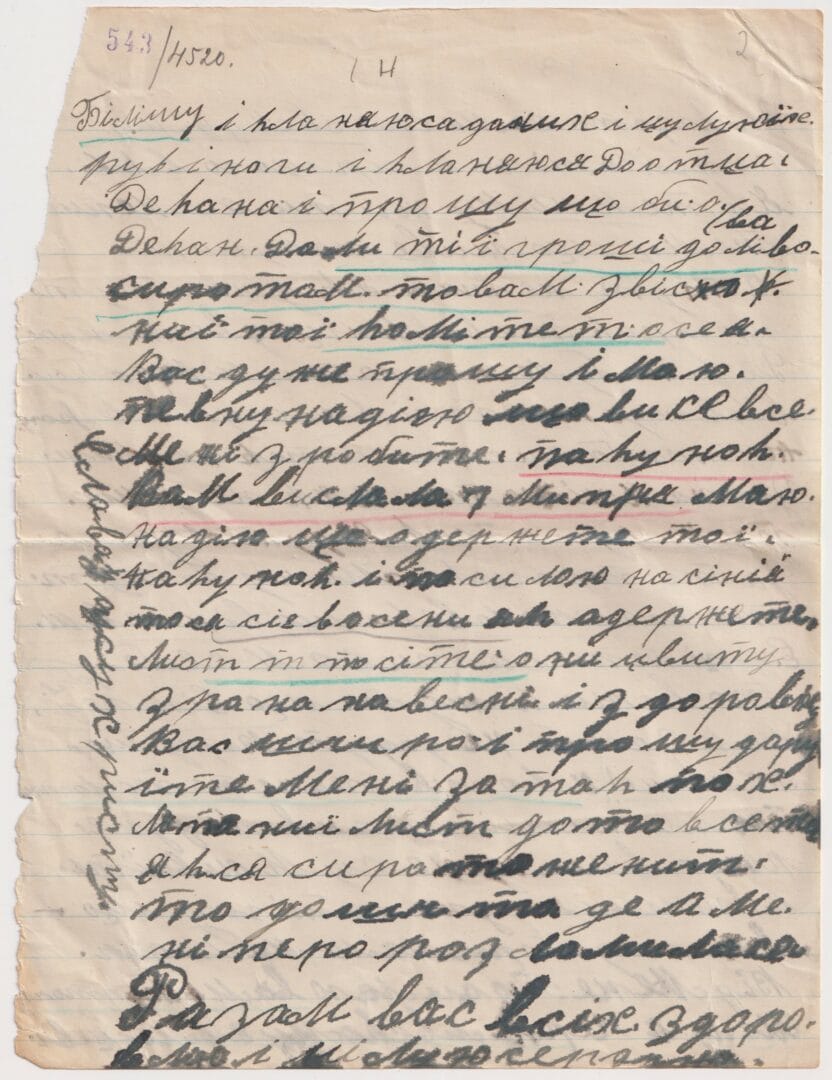

Here, it’s not like home, at every step – a wolf, every two steps – a trouble. Everywhere. For example, when I work in a household, and if there is a need to retell the phone message, I’ve to write it because it is hard to rememmber, and if you don’t know how, it’s a problem. But I’m very wise. I can do a little bit cause here if a man doesn’t know how to sign his name, they say he doesn’t take care of himself. Won’t believe he can’t. You want a closth, then write which one, I’ll be happy to send it to you, be certin. Write, and I’m very happy everyone got my gift with joy. I send you a small handkerchief and a larger one to Chernelivskyi grace[2] and bow to them and kiss their hands and feet and bow to Father Dekan[3] and ask that Father Dean give the money to the orphanages. You know about the committee of homes.[4] Asking you very kindly and have some hope you will do this for me. I sent you a package to Mitria[5], and hope you will receive it, and sending you seeds to sow in autumn. Just sow them, they will bloom in the spring and I wish you healsth and please forgive me for the messy letter, it’s damp, rainin, and my feather broke.

I give you all my best regards and kiss you hearty.

Glory to Jesus Christ (note in the margin)

And I ask you not to pay for the letters (note on the back of the last page)

Notes:

[1] The letter is addressed to Anastasia Kuzyk, a resident of the village of Butsniv near Ternopil.

[2] Meaning Fr Mykola Mykhalevych, the pastor of the church in the village of Cherneliv Ruskyi.

[3] Meaning Fr Isidor Hlynskyi, the pastor of the church in the village of Butsniv.

[4] This could be the Ukrainian Vacation Home Society founded in 1905. It organized summer holiday camps for children from poor families. Or, possibly, the Ukrainian Regional Society for the Protection of Children and Youth, established in 1917 to help children affected by the war.

[5] By the St Dmitry’s day.

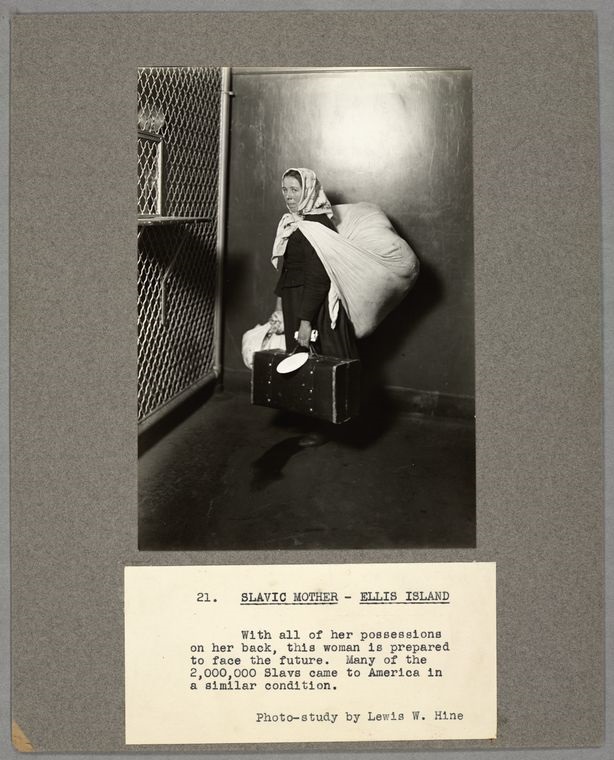

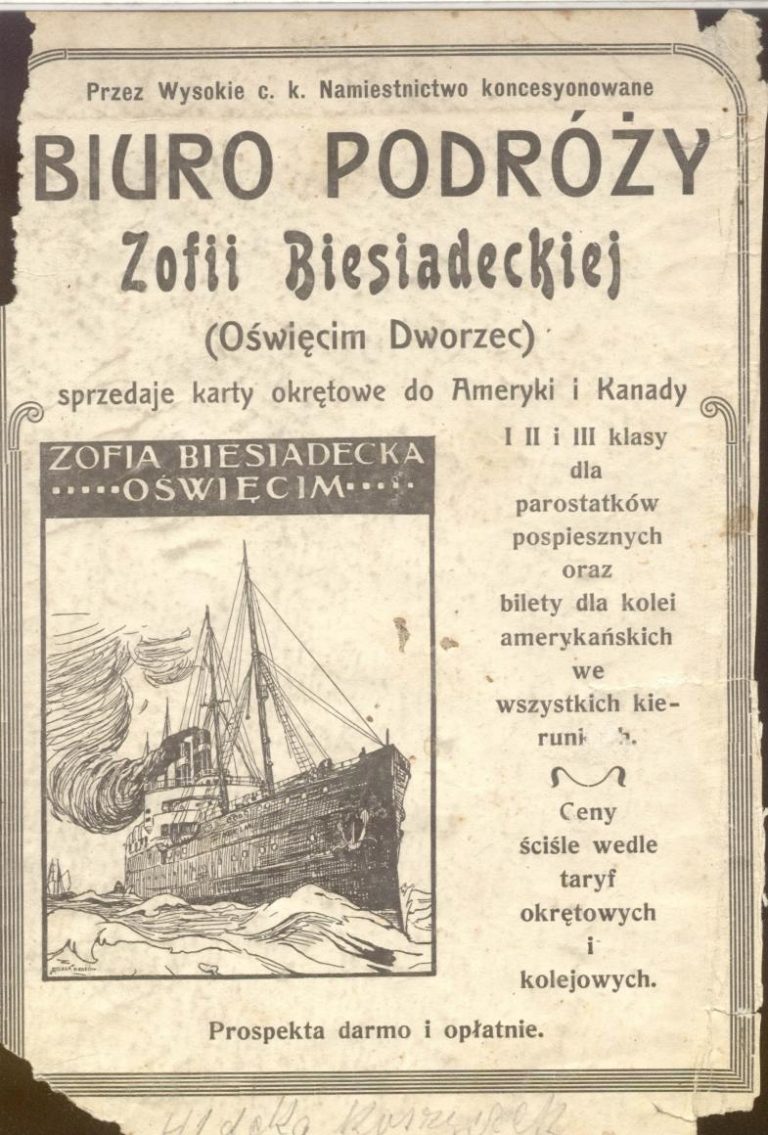

This unattributed letter was addressed to Anastasia Kuzyk, the housekeeper of Isidor Hlynskyi, a Greek Catholic priest from the Galician village of Butsniv, near Ternopil. Penned by a former female resident of Butsniv or one of the neighboring villages who had immigrated to America and resided in New Haven, Connecticut at the time of writing, the letter bears the date of 11 July 1921. It was composed in the aftermath of the recent Ukrainian-Polish conflict and the subsequent Ukrainian defeat. While the letter does not directly mention these events, it cautiously alludes to them, perhaps due to apprehension regarding censorship and potential repercussions for the recipients.

The author reflects on her immigrant experience, grappling with issues of national identity, adapting to American customs, and asserting her own agency. Her ability to write, and thus her ability to “express her thoughts to herself,” was of great importance to her in acquiring the latter. Her literacy “in a foreign land” was not only important for emotional and psychological well-being, but was also a valuable capital for her new life in America.

The Ukrainian spelling in the letter contain grammar and lexical inaccuracies; we tried to reflect those in the English version as well.