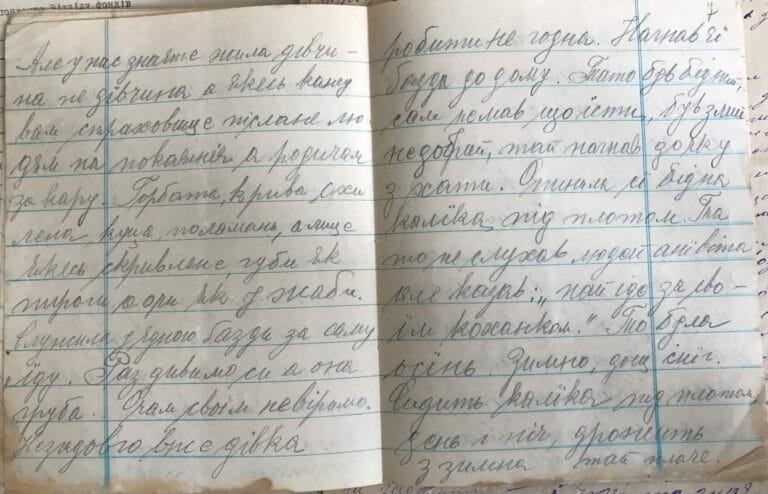

“My grandmother was telling us about the Austrian war. That the Austrians were very kind people. Really kind people. When the Muscovites came – during the Austrian government, they fought Moscow – the Muscovite people were nasty. Dreadful. Whatever you might think but that’s what my grandmother used to tell. Austrians were good people: they shared whatever they had with everyone, they were civilized. They shared with all the people.

There was someone complaining at… they complained to Franz Josef that… from the war, the soldiers complained they had been poorly fed. And he disguised, Franz Josef dressed up as… a poor old beggar. He disguised as a beggar and came here… to check the soldiers, and lined them up. That’s when he dressed back as an emperor, as a king. And he asked them to express their… dissatisfaction with his army. They answered that they were happy but for the meals. That’s how my grandmother would tell me.

Then, he took (it was winter time) some snow in his hand and made a snowball, like so [showing a little ball with her hands] and gave it to the senior, and said:

– Hand it over to all other soldiers.

There was a row of soldiers there… So, when the last soldier got the snowball, what was left of it? Little. And he said:

– See how it is! We are giving everything to you, like this snowball. But when it reaches the last soldier he is left with this… rundown pulp”.

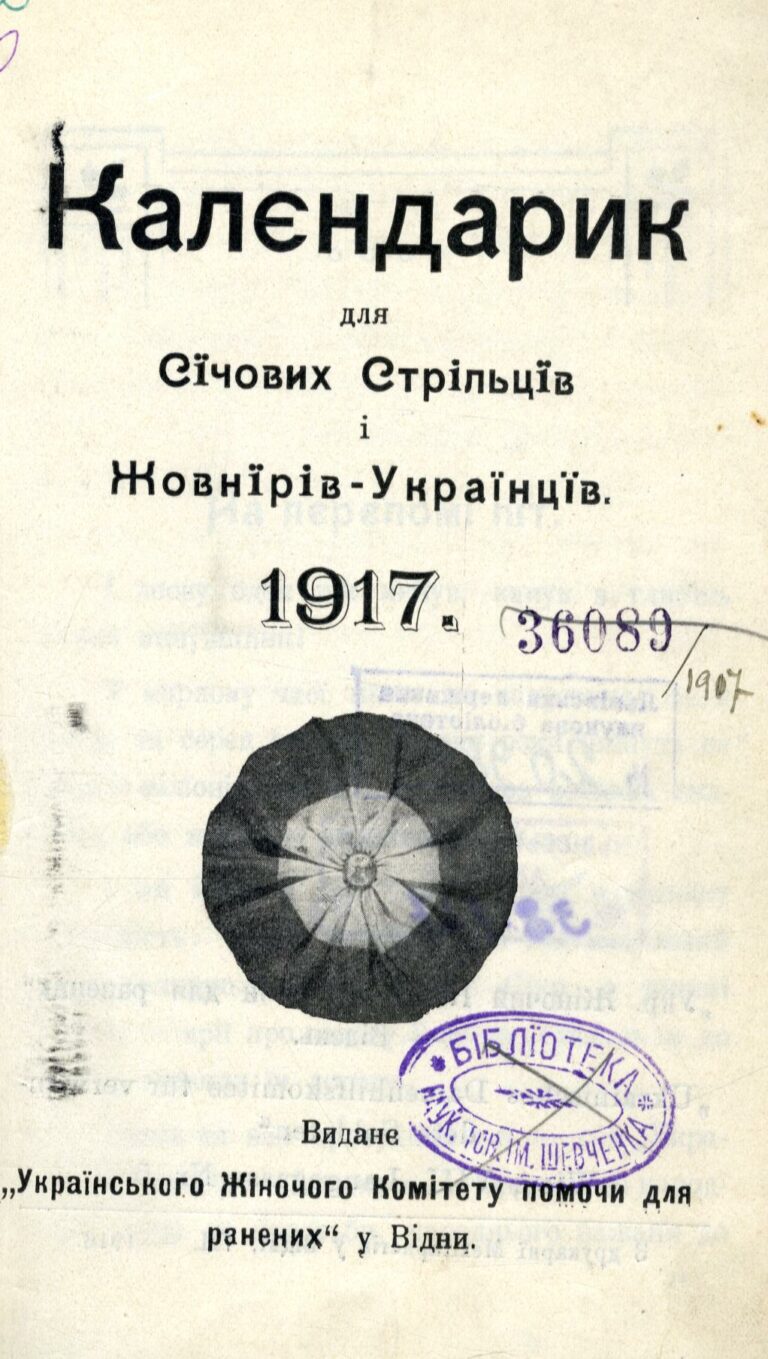

This source is the audio recording of the legend about the events of the First World War. The storyline describes an “emperor” who was incognito inspecting his army and its provisions. The prototype for the protagonist is Franz Josef I (1830–1916), the emperor of the Austrian Hungarian Empire. This artistic image shows the elements of naive monarchism. The type of “just and kind” ruler is based on his favorable attitude to Galician Ukrainians, who he took as loyal to the Habsburgs. This social myth about the “loyal troops” consisting of Ukrainians was reflected in the prose but also in songs from the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Our emperor is getting old [knows well],

he is lamenting for his children:

– You are fighting loyally, my young riflemen

I will let you go to Austria to your native land.

I will let you go home and award you with medals,

for my faithful troops are shedding their blood.

The legend highlights several key myth-based motifs such as “disguise” and “intercession of God”. Those epic motifs are traditional for the pieces of European folklore. In the Ukrainian context, it can be seen in the legends on the abolition of serfdom (a motif about the disguised emperor’s son) widespread in Hutsul and Bukovyna regions. After the 1917 Revolution, the legends about the disguised ruler became popular.

The account’s structure consists of two narrative parts: a reflective and a fabular. The reflective part offers the stereotypical assessment of the army, such as “insider” as “kind” and “outsider” as “scary”. It manifests the negative attitudes of Galician Ukrainians toward invaders who, at that time, were the soldiers of the Tsarist Russian troops (“Muscovites”). The fabular part is the legend about the emperor representing a triune image of a monarch. The image combines popular beliefs of peasants about a real person, the emperor, as a “merciful” man who cares for each individual soldier, and a type of fairytale character. The image of the disguised emperor can be seen as a variance of a trickster character who reaches his goal through his smart brain.