[p. 6-9]

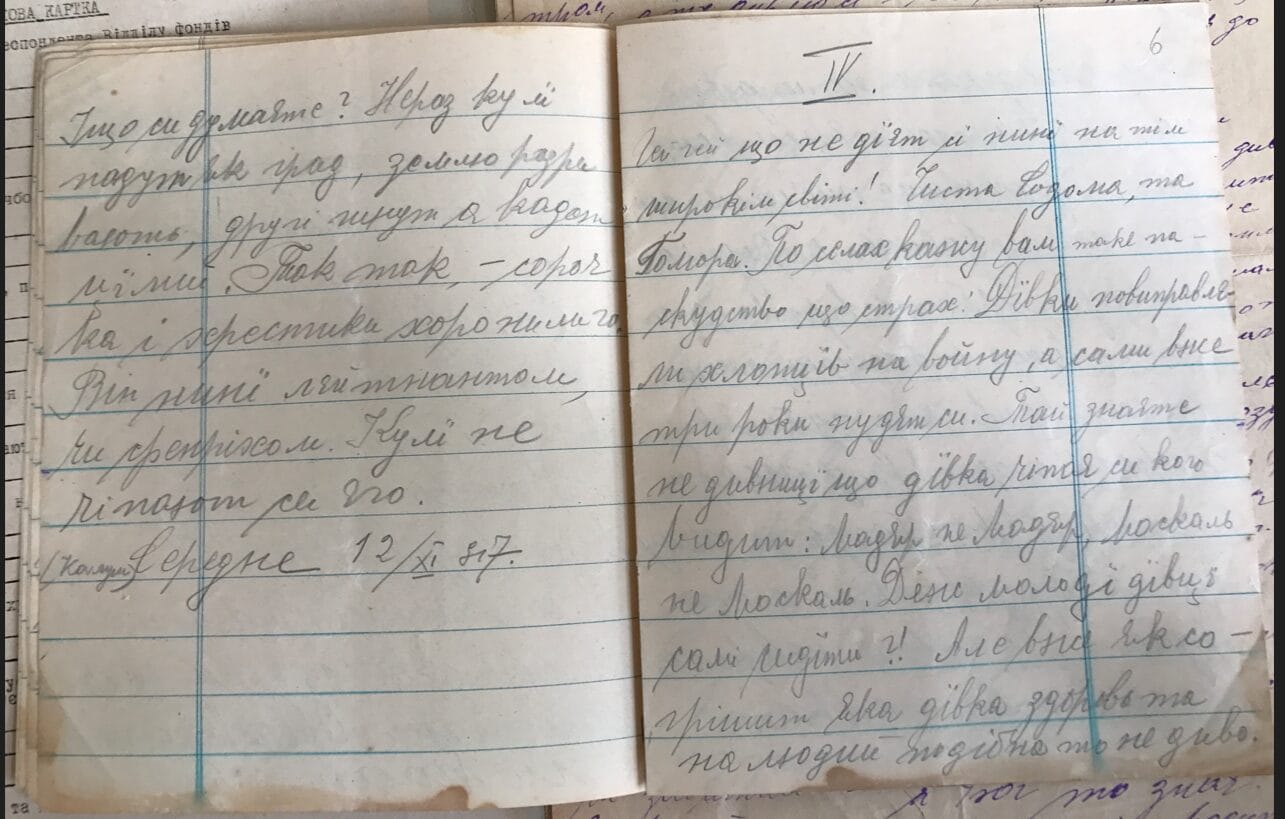

IV

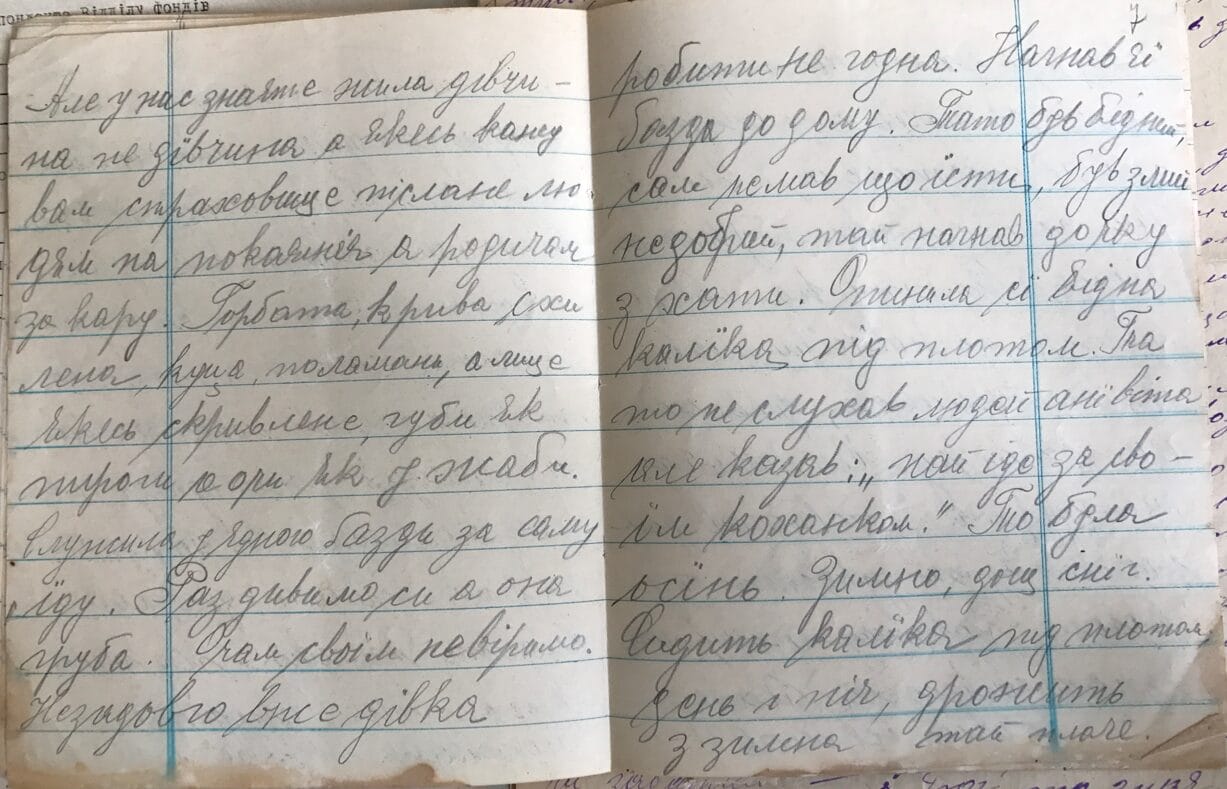

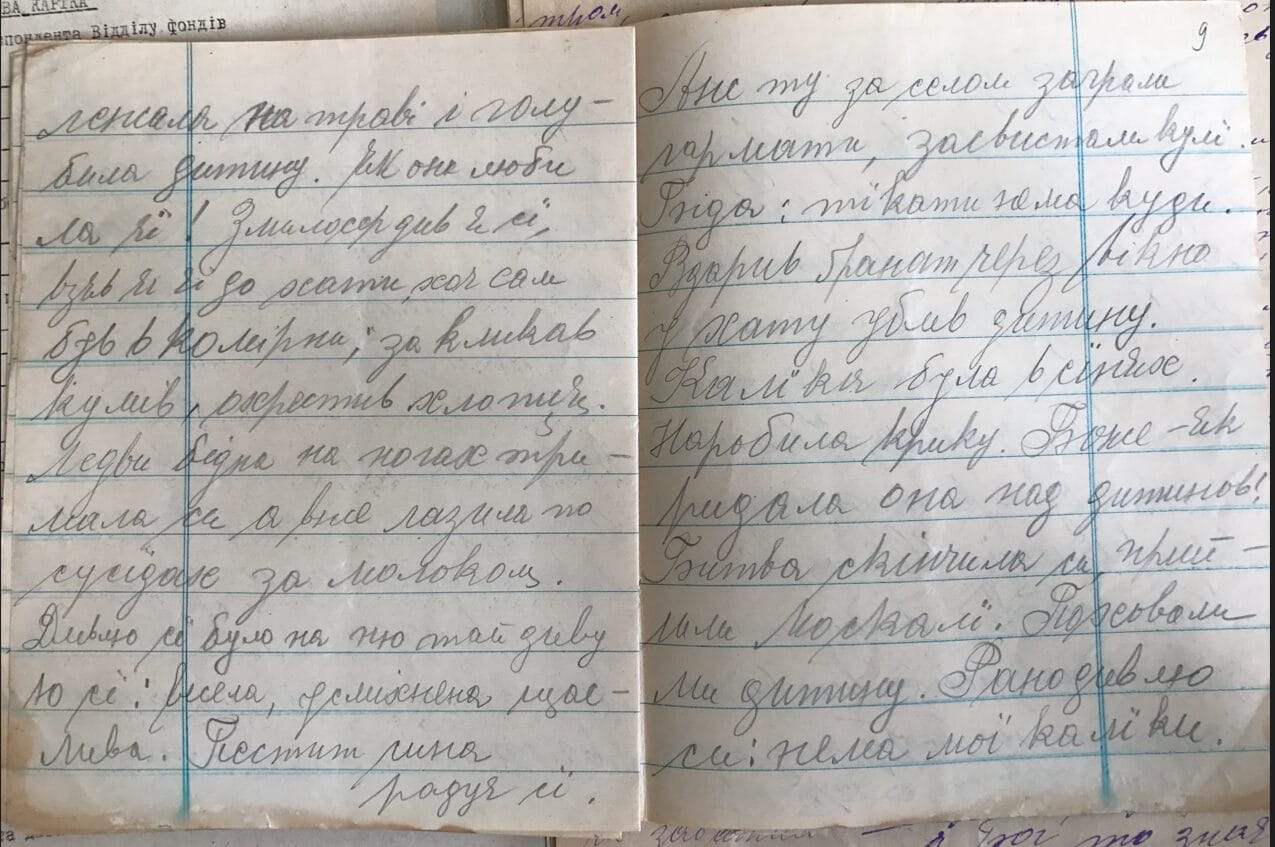

Hey, hey! Whatever may happen in this world! Pure Sodom and Gomorrah! There is such a great deal of scum and shame in the villages. Seeing their boyfriends off to the war, the girls have been staying alone and bored already for three years. It would not be surprising, you know, if a girl took a chance on anyone she would see: be it a Hungarian or a Muscovite. How can a young girl be staying all alone? And there – a peach of a girl would once sin with one of them: again, no wonder. Once upon a time a girl was living in our village: she was as ugly as death sent to the earth from hell. She was humpbacked, ugly, slouch and thin; she looked as if crippled, her face crooked, her lips looking like pies and her eyes looking like a frog’s. She was a servant working for a landowner just to get some food to eat. Once we all saw she was pregnant and couldn’t believe our eyes. The girl appeared to be unfit for working and the landowner kicked her out of the house. Her father was poor. Having nothing to eat and therefore angry, he also kicked the girl out of home. Thus, the poor crippled girl found herself behind the fence of her own house. Her father didn’t listen to anyone, saying: “Let her go with her lover”. It was autumn but it looked like winter: it rained and snowed. The poor crippled girl was sitting at the fence of her home day and night, shivering with winter cold and crying. Once I was passing by and asked her: “Girl, how did you manage to do that?” She said: “Hey, hey! The boy was handsome like a doll. He had two stars on his collar. He also gave me a white sack so that I could sew a shirt of it. Oh, I wish I could see him once again”. In saying that, the poor crippled girl was cluttering her teeth. I shrugged my shoulders and wondered: could the guy have failed to see her with his eyes opened wide? I felt sorry for the poor cripple but thought to myself: what can I do about it, having no place to live in? The Hungarian had sinned a lot with that girl. That’s a big sin! But the girl was sitting on and on at the fence and then under the bridge for a few days. Finally, sitting in the vines, she gave birth to a son. The baby boy was ripe like an apple: he was big, healthy and handsome. He was so tender as well! His mother had suffered a lot. Now she was lying on the grass and nursing her baby, being ill, barefoot and shabby. You will never understand how much she loved him. I felt mercy for her and took her to my house though my house was actually a barn. I also called my godbrothers and had the boy baptized. The boy’s mother could hardly stand on her legs, because she’d been getting about the neighbors’ houses, asking for milk. I looked at her, wondering: how happy and merry she was. She was nursing her child, deriving so much pleasure from it. But suddenly canons roared and bullets were heard whistling near the village. The trouble was that there was no place to hide. Then a grenade came through the window and killed the child. The cripple was in the porch at that time. She screamed. You would be unable to picture it to yourself how she was sobbing over her baby! The battle ended and the Muscovites came. The baby was buried. I looked around in the morning: my cripple was gone. She was lost sight of for a day or two. As I was walking through the cemetery one day, I saw my cripple hanging on an oak-tree above her son’s coffin. She didn’t want to live without her son. I thought to myself: how much love that unhappy cripple had been bearing inside. That had been a great and sacred love.

That girl’s father had had the nerve to kick his daughter out of home to the fence.

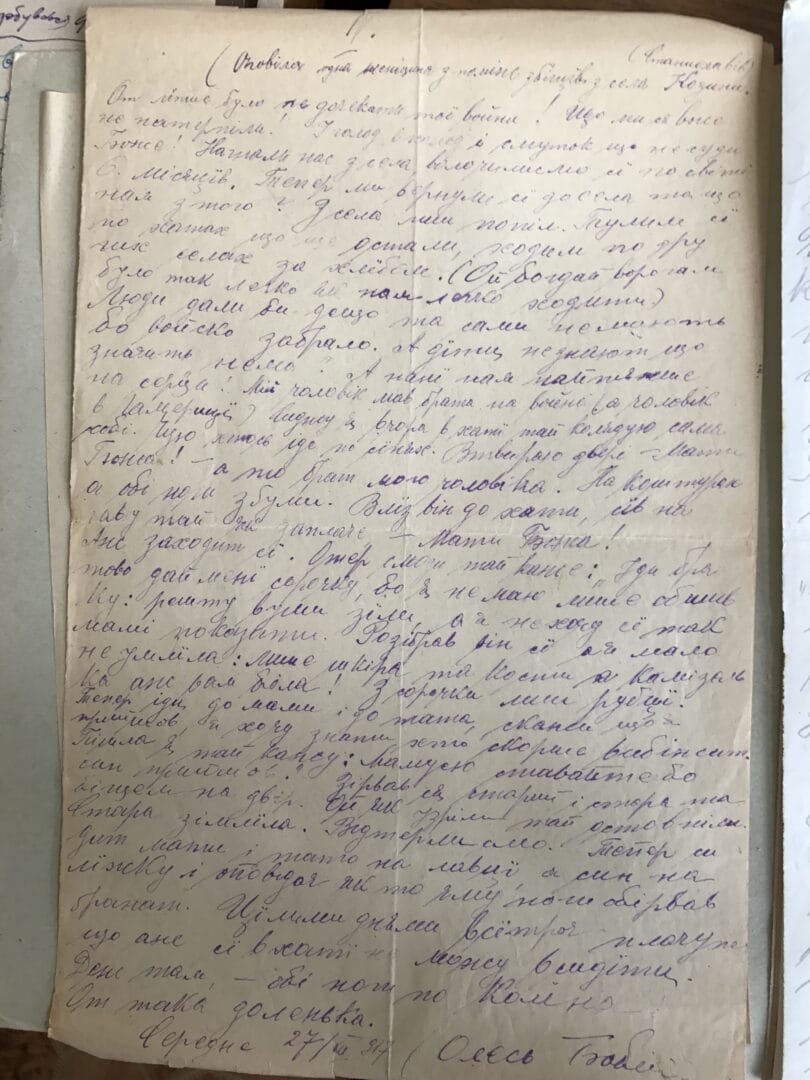

(A story told by a woman, a refugee from the village of Kozany Stanislaviv)

This source presents two narratives and perspectives on the “female” and “male” views of the dramas of the First World War. The oral narratives were recorded by Oles Babij (1897-1975), a soldier in the Austro-Hungarian army who later served as a rifleman in the Ukrainian Army (UGA). Additionally, he was a symbolist writer and the author of the lyrics to the Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) anthem “Зродились ми великої глодини” [We Are Born of a Great Hawthorn Tree]. Both texts were recorded on November 12, 1917, in his native village of Serednie near the city of Kalush (now Ivano-Frankivsk oblast, Ukraine). These stories reflect the folk-religious experience and Christian imperatives of the peasants’ negative attitude toward the global conflict. This notion is apparent from the outset, particularly in the comparison of life in a Galician village at that time to the biblical cities of Sodom and Gomorrah.

The first story recounts the tragic tale of a disabled girl who becomes pregnant by a Hungarian soldier out of wedlock. During a cannon attack, the young woman tragically loses her most precious baby. The narrator condemns the overly stringent rules and attitudes of the patriarchal traditional family of the early twentieth century towards single mothers, embodied by the heroine’s father. With no support from her family, the girl cannot bear her grief and tragically takes her own life. In the second story, the displaced person describes the devastation of her family’s home and the burned-out house she returned to after six months of wandering during evacuation.

Typical characters in the stories are nameless war victims who have retained their dignity. The imagery (featuring a kind-hearted peasant, a single mother, a mother caring for her disabled son) portrays a vivid picture of Ukrainian peasants and their emotional depth. These individuals are capable of profound love (such as a mother’s love for her deceased child), enduring suffering, and showing empathy (like a woman encountering her husband’s disabled brother for the first time). They are instilled with values of filial piety and respect for parental authority (like a soldier who does not want to present himself to his parents in a torn and soiled uniform from the front line). However, each narrator conveys a central theme through their unique story: the inherent sinfulness of war. This is depicted through the struggles of individuals faced with a stark choice: a life marked by hardship, pain, and tears, or a path that leads to death.