After the end of World War II, Soviet authorities returned to a conservative gender policy that emphasized women’s maternal roles. [1] This approach was “justified” by the severe demographic losses of the war. In 1944, the honorary title Mother Heroine and the order of the same name were introduced for women who gave birth to and raised ten or more children, while the Order of Maternal Glory was created for mothers of at least seven children. In 1956, paid maternity leave for urban women was nearly doubled to 112 days, and in 1964, this benefit was extended to rural women. By 1981, paid parental leave had expanded to a full year. However, the state’s emphasis on motherhood did not exempt women from the broad social responsibilities assigned to them. Instead, Soviet women became “doubly burdened”: along with fulfilling maternal and domestic duties, they were also expected to participate fully in public life and to work on equal terms with men in all sectors of the economy.[2] Yet despite official proclamations of gender equality, women remained extremely underrepresented in leadership roles.

At the legislative level and in public discourse, the Soviet state consistently declared that discrimination against women had been successfully eliminated. Article 121 of the 1937 Constitution of the Ukrainian SSR stated that “women in the Ukrainian SSR are granted equal rights with men in all spheres of economic, state, cultural, and socio-political life.”[3] The 1978 Basic Law of the Ukrainian SSR likewise proclaimed the equality of citizens before the law regardless of gender. Article 33 explicitly emphasized that “women and men have equal rights in the Ukrainian SSR,” underscoring the state’s commitment to providing women with opportunities for self-realization on an equal footing with men and to creating conditions that would allow them to combine employment with motherhood.[4]

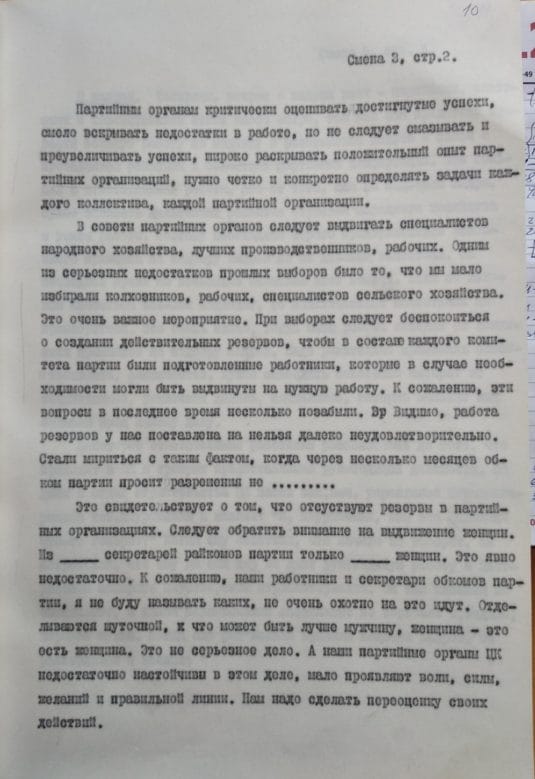

Public statements routinely highlighted the supposed achievements of the Soviet state in promoting gender equality and improving women’s living conditions, yet internal party documents painted a far more contrasting picture. These documents repeatedly confirmed the persistent problems surrounding women’s representation in various sectors and at different levels of authority. For example, a resolution of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the CPSU(b) dated November 12, 1947, characterized the work of the Personnel Department and oblast committees in nominating and consolidating women in managerial positions as “unsatisfactory” and demanded that they “correct this mistake by decisively nominating women to managerial work.”[5] “We must be bolder in promoting women,” Volodymyr Shcherbytskyi urged high-ranking officials in 1977, pointing in particular to the areas of consumer services, healthcare, education, light industry, and the food industry—sectors which, as he noted, already had a “female aspect.”[6] Government documents consistently recorded “serious shortcomings” stemming from the absence of women in leadership positions across the Soviet administrative system. Shcherbytskyi reiterated similar concerns in 1987, expressing dissatisfaction with women’s extremely weak representation even in industries he himself defined as “belonging to women.”[7] The resolution of the Plenum of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine of January 23, 1988, once again acknowledged the problem, stating that “not all party committees […] actively nominate young, capable workers, women, and non-party personnel.”[8] Yet, notably, the resolution’s operative section this time omitted any concrete requirement to increase the presence of women in leadership positions.

Despite constant declarations and repeated appeals, women remained severely underrepresented in leadership positions across all sectors. This is particularly striking given that personnel policy in Soviet Ukraine was tightly controlled by the Communist Party through the nomenklatura system. This mechanism required the prior approval of candidates for leadership posts (as well as their dismissal) by higher-level party committees. The same applied to candidates for deputies: although they were formally nominated by labor collectives, these nominations merely legitimized decisions already made by the Party. In other words, the Communist Party possessed full capacity to regulate the gender composition of governing bodies and to increase the number of women in top positions.

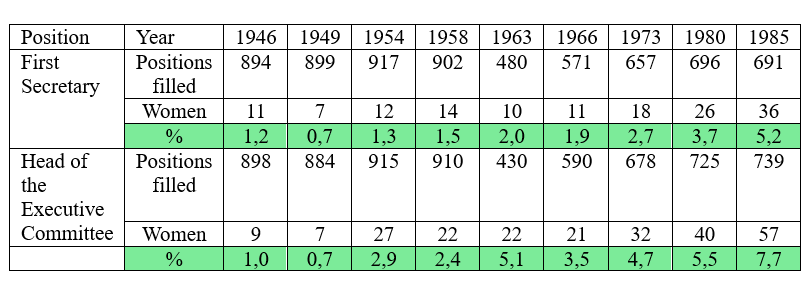

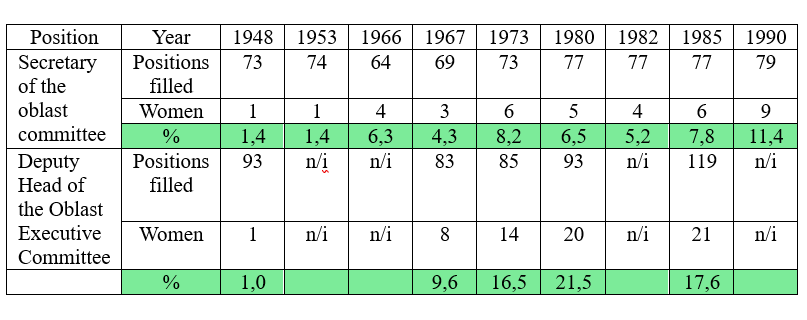

Although the number of women in leadership positions within local (district, city-district, and city) party committees of the Communist Party of Ukraine, as well as among the heads of executive committees, did grow over time, it remained far from anything resembling gender parity. As the table below demonstrates, the share of women heading party committees almost never surpassed 5%. While the proportion of female heads of executive committees was typically nearly twice as high as that of party leaders, it still never rose above 7.7%.