Many stories could illustrate the struggles of Ukrainian women as members of the Ukrainian underground during World War II. One is the story of Marija Savchyn, who in 1939, at the age of fourteen, joined the female youth section (iunky) of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (Orhanizatsiya Ukrayins’kykh Natsionalistiv [OUN]), which spearheaded the Ukrainian nationalist movement. While in high school during the Second World War in Przemyśl, Savchyn joined the Ukrainian underground. From 1944, she was involved in the Ukrainian Red Cross, an organization created in 1943 to conduct training, provide medical care, and tend to the wounded. In 1944, she was also trained as an intelligence agent. In the spring of 1945, Savchyn married an OUN deputy leader and the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (Ukrayins’ka Povstans’ka Armiya [UPA]) North commander, “Orlan” Vasyl Halasa. In 1944–1945, they lived in a hideout with a couple of other UPA members. When she realized she was pregnant, Savchyn left Ukraine for Poland where she gave birth to her child. Her plan was to move westward to continue the fight for Ukrainian independence from there. But while hiding with her baby she was caught by the Polish secret police. She escaped by jumping out of a window but had to leave behind her infant boy, who was later adopted by secret police officers. When she was arrested by the Soviet secret police, she was only shown a photo of her child with his new parents.[1]

Savchyn’s story shows a proactive and committed life, a life full of painful personal decisions and dramas. Yet a similar fate was experienced by many other women involved in the OUN and the UPA. The UPA, formed in 1942, mostly engaged in underground warfare against Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, and Poland. Long before the war, from the early 1930s, Ukrainian women were encouraged to join the OUN. After war broke out, women served as liaisons, were assigned to specific units as nurses, and were involved in espionage. Historians usually situate the moment of the most intense female participation somewhere in the middle of 1944, when the Soviet Red Army invaded western Ukraine following the expulsion of the Nazis.[2] Feminization of the Ukrainian underground was not a deliberate approach but rather caused by the need to keep the underground network running when activities of male members were extremely restricted. This period was also marked by the mobilization of village girls.[3]

Savchyn’s life illustrates the limitations of women’s agency in the militarized and highly masculine world of partisan warfare. This proactive woman had to withdraw from sharing her personal opinions once she married an OUN leader. Her story also points to the gender-based violence that women often experienced. Savchyn had to face her pregnancy and childbirth alone in a foreign country (Poland), fear for and loss of her child, and, eventually, difficult interrogations. But these painful experiences are only one example of the many hardships that women faced, from male dominance to sexual abuse. To begin with, underground relations were officially frowned upon, despite how common they were. When they actually happened, the women usually had to pay the heavy price. Marriages were not encouraged in the underground, and, as a result, many sexual relationships and pregnancies remained semi-secret, at best. In the underground, sexual norms were more relaxed than among the general Ukrainian population.[4] Often, mothers-to-be were discharged from the UPA and sent to lead a life in the open with fake documents. These women were considered a weak link for the underground and were usually watched closely for signs of potential risk. In many cases, all links with them were severed, and they were left on their own in a completely new environment. In cases when a couple insisted on marriage, the commander’s approval was required, especially when one of them was not an insurgent. “The leaders considered such cases very carefully: will the bride undermine the insurgent’s morale or persuade him to leave the struggle, or, perhaps, through her, the NKVD may try to turn him into an agent,” wrote one of the underground members, Anna Karvanska-Baylyak.[5]

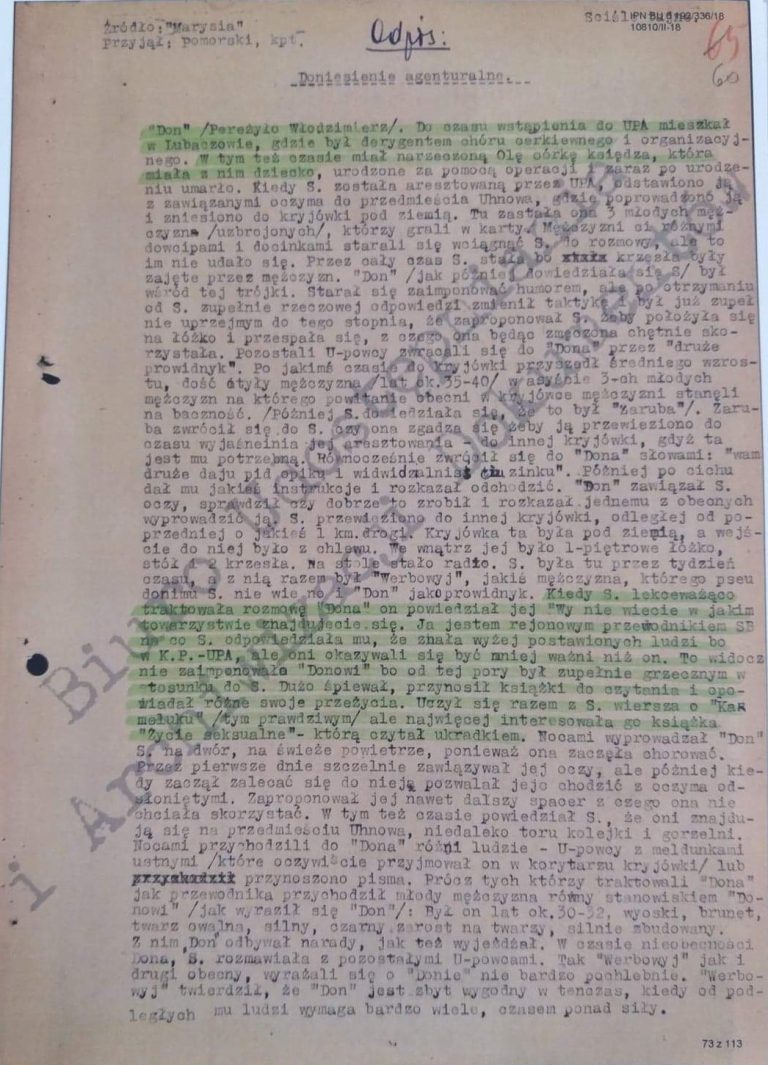

One of the least explored and by far the most painful aspects of women’s engagement with the Ukrainian underground was the use of women as sexual tools, either by the underground or by those the underground was fighting against. As Jeffrey Burds argues, members of the Ukrainian underground advised women to have sexual relations with agents of the Soviet security forces. The Soviets responded by creating a network of informants to collect intelligence data on women who were in relationships with insurgents. As a way to convince their lovers or husbands to cooperate with the Soviets, the Soviets forced these women into sexual intercourse through violent torture, rape, and threats. These practices pushed UPA leaders to decrease their reliance on women at the beginning of 1945.[6] Women who remained in the underground, toward the end of the war, were pushed into the so-called deep underground, which meant that they reorganized the remaining units into a strict military underground that was supposed to survive until the expected third world war. Their ultimate goal was a national uprising for Ukrainian independence. They devoted more attention to educational and propaganda activities through different kinds of illegal publications. Poland was the window into the world for propaganda activities, as well as a contact point between the Ukrainian Soviet Republic and the West. From Poland, UPA members also traveled further West to join emigrant UPA communities, while trying to get Western authorities to pay attention to the Ukrainian cause.

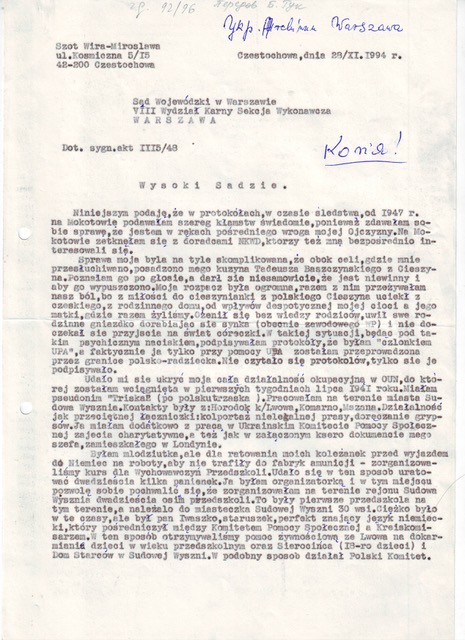

Ongoing involvement in the underground also meant that women and men were exposed to intense monitoring of the secret police on both sides of the new postwar border: the Soviet and Polish secret services that tried to eliminate Ukrainian insurgency. Many UPA members were imprisoned on Polish territories. Many female UPA members traveled to Poland, where they stayed in cities located near the border, such as Przemyśl or Jelenia Góra. There, they were supposed to lead an open legal life or continue their underground activities under the cover of a legal life. Many of the women were born in pre-1939 Poland and, hence, had Polish citizenship, which was supposed to facilitate the process of obtaining Polish documents. While in Poland, they were supposed to provide messengers and couriers traveling from Ukraine to Western Europe and further to the United States with a place to stay. They also looked for ways to deliver UPA propaganda materials to the American-occupied zone in Germany. Many of these women and men were quickly caught and imprisoned.

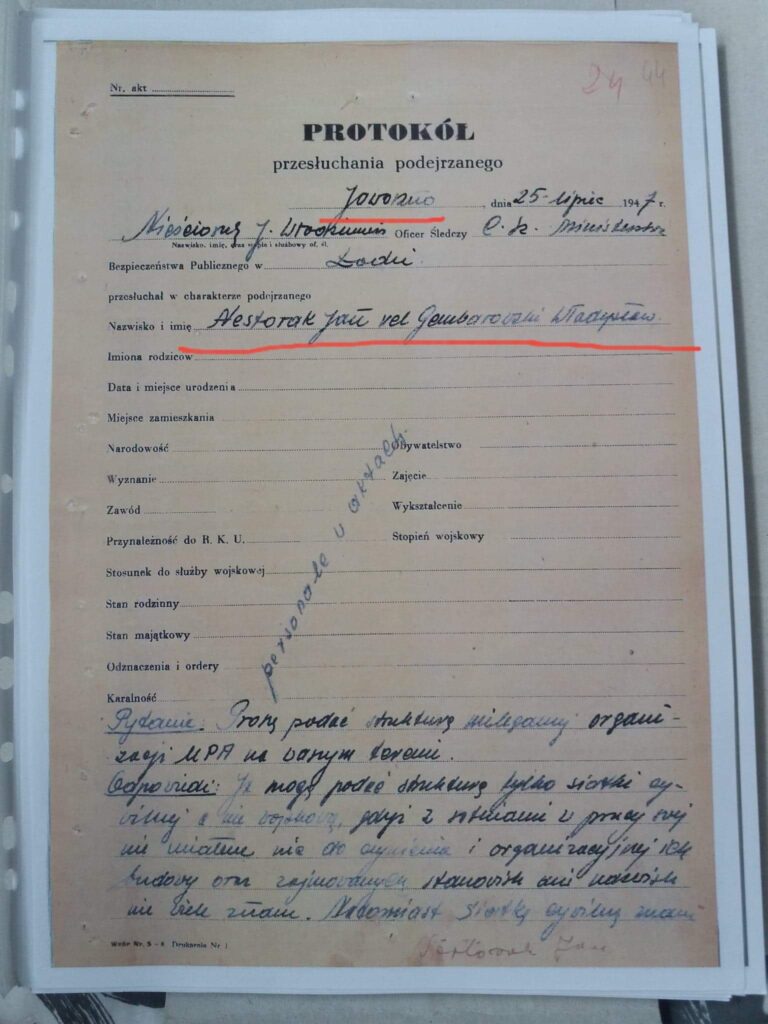

The number of imprisoned Ukrainians is difficult to establish, as only partial data is available. In February 1945, a work camp for Ukrainians in Jaworzno, in southern Poland, was created.[7] According to the first report from Jaworzno, in Jaworzno alone, in March 1945, 945 men, 935 women, and 31 infants were held there. The camp existed until January 1948, when many former Jaworzno prisoners were transported to other prisons in Poland. Ukrainian prisoners were also confined in other sites, such as Mokotów prison in Warsaw, Fordon near Bydgoszcz (prison for women), Inowrocław prison (prison for women), Zamek Lubelski, Rawicz, or Wronki.

Ukrainians began to enter the penal system in larger numbers in April 1947, when Polish authorities launched Operation Vistula. For Polish Communist authorities, the presence of large Ukrainian minorities who were militarily predisposed constituted a problem. Operation Vistula, the forced resettlement of the Ukrainian population living in southeast Poland, was designed to disperse and assimilate Ukrainian communities into Polish society. The goal was to liquidate UPA units and transfer Ukrainians from the southeast border zone to northwestern Polish territories, which were added to Poland after the war. The campaign lasted three months, resulting in over 40,000 displaced people. The UPA soldiers discovered during the displacement were imprisoned in Jaworzno. In addition, with forced resettlement of the Ukrainian population from Poland to the Ukrainian Soviet Republic, authorities planned to eliminate facilities and people who were willing to support the Ukrainian underground.

UPA members arrested in Poland were accused of violating Article 85 of the Small Criminal Code. It established severe punishment, ranging from a long prison sentence (ten to fifteen years) to a life or even death sentence, for their attempt to deprive Poland of part of its territory. Halina Martyn, a UPA member from the 1930s, withdrew from UPA and moved to Poland in 1944. She was arrested in April 1949 and given an eight-year sentence for publishing Ukrainian nationalistic poems in illegal UPA brochures. As incriminating evidence, the court noted “her high intellect, her previous political activity, and her political skills.”[8]

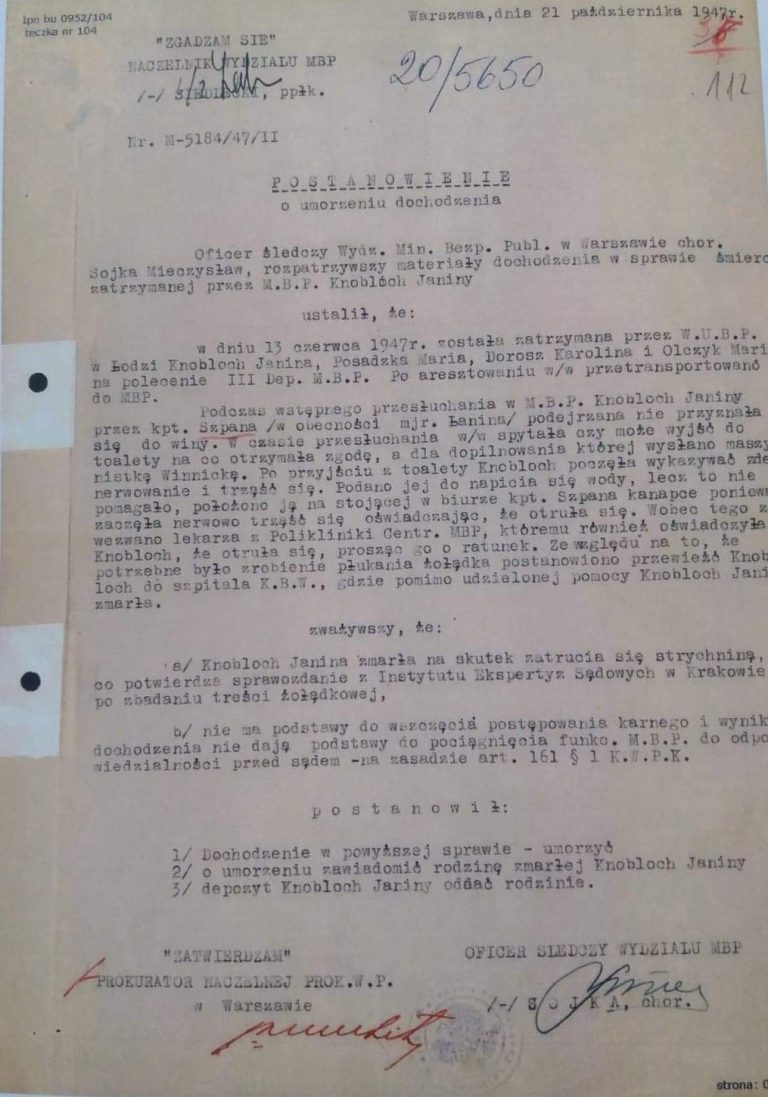

There does not seem to be any systematic approach to torturing women, but it does appear to have been more common in the first three years after the war. Torture was prevalent in Mokotów prison where the most violent officers worked, such as Jacek Różański and Anatol Fejgin. It was also frequently used in local and smaller Ministry of Public Security (MBP) outposts, places that were typically not well monitored. One such place was a prison in Rzeszów, where many Ukrainians were detained and tortured.[9] Irina Tymochko-Kaminska, imprisoned in 1947 for her involvement in the UPA, was kept in a basement in Rzeszów, in southeastern Poland, where cells called “tombs” were full of rats that roamed near the uncovered containers provided for excrement.[10] These horrifying conditions bore fear and desperation.

Literature:

- Maria Savchyn, Thousands of Roads: A Memoir of a Young Woman’s Life in the Ukrainian Underground (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2001).

- Jeffrey Burds, “Gender and Policing in Soviet West Ukraine, 1944–1948,” Cahiers du Monde Russe 42 (2001): 286–89.

- Burds, “Gender and Policing in Soviet West Ukraine,”286–89.

- Oksana Kiss, “National Femininity Used and Contested: Women’s Participation in the Nationalist Underground in Western Ukraine during the 1940s–50s,” East/West: Journal of Ukrainian Studies 2, no. 2 (2015): 72.

- Karvanska-Baylyak, quoted in Kiss, “National Femininity Used and Contested,” 71.

- Burds, “Gender and Policing in Soviet West Ukraine,” 297.

- Kazimierz Miroszewski and Zygmunt Woźniczka, eds., Historia martyrologii więźniów obozów odoobnienia w Jaworznie 1939–1956 (Jaworzno: Muzeum Miasta Jaworzna, 2002), 58–70; and Kazimierz Miroszewski, “Powstanie i funkcjonowanie Centralnego Obozu Pracy w Jaworznie, 1945–1949,” Dzieje Najnowsze, no. 2 (2002): 23–40.

- “Akt oskarżenia Haliny Martyn,” 1949, Maria Pankiv’s Private Collection.

- Anna Karvanska-Baylyak, Vo imya Tvoye (Warsaw: Ukrainskij Archiv, 2000).

- Irina Tymochko-Kaminska, Moya Odyseya (Warsaw: Ukrainskij Archiv, 2005), 208.

This essay was written based on my book: Anna Muller, If the Walls Could Speak (Oxford University Press, 2018). The author thanks Mariusz Zajączkowski for his help and sharing of some of the sources with her.