Interrogations

The investigator was already waiting at the gate. They take me to the 4th floor. As I learnt later, all Ukrainian people were re-interrogated on that floor. We enter the room, where two people were already waiting for me. The convoy man told me: “Ja — Michał Bajowski” [I am Michal Bajowski.]. The other two also said something but I could not make it out. One of them took personal details. Then, he looked up and stared at me: “Mam nadzieję, że będziesz mówiła tylko prawdę, odpowiadając na wszystkie moje pytania” [I hope you will be telling only the truth when answering my questions.]. And then: “Ty należałaś do OUN i byłaś w lesie z UPA? Z kim masz kontakt na Zachodzie?” [Have you been the OUN member and stayed in the forest with the Ukrainian Insurgency Army? Who do you keep contacts with in the West?]. The questions kept pouring one after another. He started calling the soldier code names of commanders, of a hundred’s unit leads, of the district leads. He asked every detail about the Command in our region, especially about “Zalizniak” and “Kalynovych.”

To all the questions, I kept answering: “I know nothing, about anyone. I haven’t seen anything. I have no contact with anyone. I do not know.” Then, he asked: “To dlaczego ty uciekłaś do Krakowa? Od kogo dostałaś dokumenty?” [Then why did you flee to Krakow? Where did you get the IDs?]. I realized they knew many things about me. I answered that I lodged the documents myself. As to other questions, I kept silent, and never admitted anything. Each answer could entail other questions and squeeze other information for them. I knew that as soon as I started admitting some things, it would be hard to get out of that. The interrogations were getting more severe, they beat and tortured me. Bajowski went loose the most. He would brandish with the rubber whip as a madman (the whip had a rod inside, and a piece of metal on the tip). He would punch wherever he could: in the head, in the back, the arms, and legs… Raging pain, helplessness, and more beating and punches… Some screams that I was not able to make out any longer, with no understanding of the things around. The only thing I felt like becoming small and hiding somewhere, so that they left me alone, to avoid the beating.

At some point, the butcher paused. But in a moment, he jumped on the chair and quickly spooled my long and thick hair on his arm, and lifted me up. He kicked wild. I was suffocating from pain and punches. Then, he must have got tired and let me down. I dropped on the floor and my executioner continued raging. He swung his blood-stained hand with the hair clumps and pieces of skin stuck to it. He cursed me, pulled the clumps off and threw them at me. It took some more time for Bajowski to try his torture tricks. After several hours of torture, they dragged me to the cellar and threw me there on a coal pile like some sort of junk. I was lying face down, I could barely move, and my body anguished with pain.

I stayed there, half-conscious, until late at night. Then, through the doze, I heard some quiet words: “Zozulia.” I could not recognize anyone but I looked back and saw him: “Oh, God!”. It was a fighter from one of our units, “Samchuk” (Ivan Karkhut from Teplytsi). How is he here, in that corridor? He recognized me. But instead of joy, I was wrapped with fear: what if he gives me away? How do I know his tactics in the interrogations? “I don’t know you,” I said to him. It meant that we allegedly did not know each other in the investigation. He answered: “I don’t know you, either.” I sighed with relief. He came closer to the bars and asked: “Are you hungry?”. I was so feeble that I could hardly answer back. He had a piece of bread with him and tried to throw it at me, but he failed. The bread flew over and beyond. I did not even look where it landed. “Samchuk” disappeared the same as he came, and I have never seen him since.

Some time after midnight, they called me to the interrogation again but I was not able to stand up. Two guards came up and dragged me off that pile of coal. They tried to lift me up but was not able to stand on my legs, and I shrieked from the piercing pain and fell. My body ached, and I suffered the intolerable pain at every touch. They lifted me again and took me outside. The Butcher Bajowski and other two men were waiting there. He immediately started cursing me and ordered: “Szybko na górę!” [Rush upstairs!]. That meant going up the stairs to the 4th floor where they conducted their interrogations. He pushed me in the back, I fell down, and he started kicking me on the lower back with his boots. Every step I climbed was accompanied with the kicking. I crawled to the 2nd or to the 3rd floor and fell, more dead than alive. It made Bajowski rage, and he went on whipping me as hard as he could ordering me to stand up. But I could not. I was limpen. My executioner was getting even more outrageous and ready to kill me. In the end of the corridor, there was a woman (may be, a cleaning lady?). Desperate from my helplessness, I started calling her, screaming that I wish that butcher shot me. I did not know who to ask for help. That woman must have been scared and ran away. Then I screamed: “God, help me! Dear God!”. It made my executioner even more infuriated. He would punch and kick me more, I can’t even remember how long it lasted.

They brought me back to senses by pouring a bucket of cold water on me. Then, they lifted me and made me crawl on. I crawled with my hands and could hardly manage another staircase. Bajowski was impatiently rushing me and kicked with his boots. Eventually, when I reached the room where my torture of interrogation was supposed to continue, he pushed me so hard that I flew across the room and only landed at the tiled stove, and cut open my sore head on the right. The blood was spilling hard. I was reduced to a pulp and overwhelmed on the floor. The shriek: “Wstawaj!” [Get up!]. I was lifted and thrust on the chair, and they started beating me, two of them together, all over. I was lying there helpless. They tore the clothes off me, and my shoes, and kept beating me half-naked. I was not feeling anything any more, I did not even cover myself. They would pour the water onto me and yell: “Mów, gdzie chowają się twoi koledzy!” [Tell us where your companions are hiding!]. The only thing I could barely utter was “I don’t know.” They stopped the beating. Then, they started talking among themselves, and shortly after, tossed me face down, and continued beating on my feet and the heels. What an unbearable pain! I was suffocating from it. The head kept bleeding, and in my mind, I kept praying: “Dear God, I’m not going to survive! Help me!”. Then, there were more yells above my head: “Mów! Mów, zacięta banderowko!” [Speak! Speak, you stubborn Banderovite!]. They mostly wanted me to tell them where our fighters were hiding who moved to Western lands following our people displaced during the “Wisla” operation.

Each blow on the heels reverberated with the outrageous pain in my head, and my torturers knew that. I kept repeating half-conscious: “I don’t know, I don’t know…”. how long has it taken? Felt like eternity. They kept beating, asking, and pouring water on me to bring me to senses, and then they continued on, and on… They were always three. Finally, one of them said: “Ja nie mam sumienia więcej bić” [I don’t think we should continue to beat her.]. And he stopped beating me, but Bajowski still did not have it enough, and wanted more blood and tortures. He was raging he was not able to beat anything out of me or find anything out. He said: “W moich rękach mężczyźni śpiewają, a ty, zacięta banderowko, nic nie gadazh!” [Even men start singing their testimonies in my hands, and you, the stubborn Banderovite, are not speaking!]. I had bells ringing in my ears, my head was spinning, all of my face was covered in blood, and the body was one sore wound. Half-conscious, I weakly whispered: “Jesus Christ! Jesus, save me!”. Bajowski’s face distorted in a miserable grimace, and he sizzled: “Jesus is a f…”. “Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they are doing!”, I muttered. Bajowski replied to that: “To ja jestem Boh. Jak ja zechcę, to ty do rana zdechniesz i nikt nie będzie wiedział jak. Ja to mogę, słyszysz ty… ja Boh! Ja!!!!” [I am the God! If I want, you will be dead by the morning, and no one will ever know how. I can do it! You get it? I am God! It’s me!!!]. I kept silent, powerless, and I could only utter: “Jesus! Jesus! Lord, have mercy!”. I could not fell anything, and lied there in dirt and blood…

At midnight (I think now it was midnight) the chief of Security Department came to inspect things. Later, I learned that his name was Osetek. I am certain that it was God who brought him there on that savage night. He made him get out of his warm bed to save me from death. I have not seen him, I only understood it later, when everyone raised and reported to him, it was clear it was their chief. I was lying there moaning and asked for some water… he approached me, stayed there for a moment in silence, and then told them to give me some water. One of them came up with a bottle of water and poured it into my mouth. I opened my eyes and saw a man above. “Czy złapaliście ją z bronią w ręku?” [Have you caught her with the gun in her hands?]. They answered: “Nie” [No.]. “Czy złapaliście ją na gorącym uczynku, że zabiła kogoś?”. “Nie”. [Has she killed anyone? – No.] And next he goes: “Taką młodą kobietę doprowadziliście do takiego stanu? Z mężczyzną tak się nie postępuje. Ona jest konająca, co z nią będzie do rana? Pomyśleliście o tym?” [You have brought such a young girl to this condition. One does not even do it to men. She is dying, what’s going to happen to her by the morning? Have you thought about it?].

He also said some other things but I could not hear any more. The humming sound and the noise in my head drowned all voices. Somebody covered me up with my clothes. Two of them lifted me by the armpits and dragged me along the corridor, then downstairs and back to the cellar. They threw me to the room where all the sewage and waste was disposed from the bucket. There was a canal that ended with a window hole. They closed the door… they must have hoped that I would half-consciously roll down to that groove, and they would later declare that the girl committed suicide. I lied down on the cold concrete floor for some time, and it was February. Coming back to my senses, I felt extremely thirsty. I moaned and begged: “Water, drink…”.

At that time, one of the guards heard my moans and entered the cellar. He lit the room with the flashlight and saw me there. I must have been in such a non-humane condition that he got scared and rushed upstairs while leaving the door open in a hurry. I did not quite realize what I was doing but I started crawling on my belly to the exit. I crawled on the last leg on and on… That must have been a kitchen, or something, I am not sure how I got there, whether I saw or felt that bucket. I crawled closer and lapped down whatever was in. I am not sure what liquid that was, probably, water, or may be something else. I could not stop drinking…

In a blink of an eye, two guards were next to me. They moved the bucket aside, and lifted me. They wanted to put me standing but failed, I was not able to stand. They took me barefoot and half-naked and kept me up to bring me back to my senses. All of a sudden, I felt like I was cuddling in my mom’s arms!… And I am telling her how I was tortured. I am telling my mom how good it was that it was just a dream, that it was all happening in my dream… I opened my eyes and saw the walls, the unfamiliar walls, and some people holding me under my arms. They asked me whether I knew where I was. The guards said we were in Rzesow, at the Investigation Unit. They took me to cell No.14, where I stayed initially. They put me on the bare bunk, and then, when they noticed my coat, they placed me on one half of it and covered with another one. There was also a head kerchief. They wrapped my bare bloody feet with it. I learnt about it all later, from one of them.

I stayed there for a long time, and I could not move. The next-door cell had Polish men from AK and WiN. Later, when I started walking again, leaning on the wall, they told me I was groaning hard and kept asking for water. They could not sleep, they did not know what was happening behind the wall. They started knocking on the door, and asking the guard to check on me and help me. I could not remember any of it. For me, time did not matter at all. I was not able to see anything because the face was so swollen. I hardly opened one eye and saw my poor black hands, and the swollen blood-stained fingers. That is when I came to realize what they did to me. I could not speak, there was a lump in my throat. I could only cough out the dry blood. I looked down on the ground. It was concrete, and full of snow blown by the wind through the hole in the window all boarded up. This is when I felt how cold it was, and the cell only had me and the rats.

My solitude did not bother me. At midday, a guard came in and greeted me with the following words: “Ty zacięta banderowko ukraińska, zdechniesz tu, już niewiele ci zostało” [You stubborn Banderovite, you will drop dead here, you don’t have it long.]. A large can from the US soup was standing near me. It was supposed to function as a bowl. At some point, they poured in some coffee, and then added some soup for lunch, and all of had long gone bad and frozen. He said: “Dlaczego nie zjadłaś? Jak to wszystko wyliżesz, to dostaniesz świeże jedzenie” [Why have not you surrendered? When you lick all of that out, you will get some more food.]. I have not felt hungry, probably because of the high fever. I only dreamt of one thing – to have some water or coffee.

Hunger Strike

It took place before Easter. Local Polish women received the Easter packages. Ukrainian women received none. Most of us either did not have any family left, or they stayed far away. Or, sometimes, they had no idea of our whereabouts. Solidarity is a big thing in the prison. Polish ladies shared with us their festive treats. But our festive mood was impeded by Inglot, an old lady, who said she had a premonition that they (prison management) could punish us and take away the packages. It was decided to eat it all fast at breakfast and get full, and the remaining food staff could be hidden. I remember how Iryna Vovk hid several lemons behind the wooden pillow, inside her personal belongings. Emma, who had the TB, climbed the 3rd bunk on top and wanted to hide some sugar and fat there. But at that very moment, the door swung open and a prison chief, an investigator, and some more men entered the cell. They when they caught Emma so off-guard, they said: “A ta kawka co tam robi? Co chowasz?” [What about that gaper over there? What are you trying to hide?]. Poor Emma went down, and they took away all the food from her. The investigators Sikora and Swiderski were raging. They punished our cell with hunger: they only gave us bread and water that we could take only from the bucket. They did not want to give us any hot water or coffee. We protested and started our full hunger strike, we refused to eat anything. Every day, they brough a quarter of the bread loaf for each of us, and the pile kept growing. But none of us touched that bread, although we were starving. That continued for some three or four days. Eventually, they called Liuda Kot, she was in charge of our cell. They asked her why we started the full hunger strike. Liuda answered that we had been punished several times: they took away all the Easter treats, we did not receive any warm water or coffee, and we were made to drink cold water, and also from the bucket, which was unsanitary. They also took away the bench from the cell so that we could not sit, we were not allowed to touch the beds, we were not allowed to sit on the floor, and we were made to stay standing from the morning “Appell” [head check] until the evening head-check. That was so many punishments, and also when we were not guilty of anything.

It was Sunday. We were kneeling and whispered the Holy Mess. All of a sudden, the door opened and the special unit inspection entered. At the sight of such high-ranking prison authorities, you needed to stand to attention and report. But none of us moved. We kept praying. They stayed there watching us for several minutes, and left. When we finished the prayer, and stood up, the door swung open and several buckets of cold water was poured in. they ordered to dry that floor within 15 minutes. We got to collect that water with whatever we could to finish by the deadline. After that, another check-up was held in our cell. Each of us had their own belongings for women stuff. It was all extremely poor, especially for the Ukrainian prisoners as they have been imprisoned for a long time then. The stuff got all worn out, and we did not have anywhere to get anything new. During the inspection in the cell, there was also a lieutenant (or, may be, a captain?) attending. His eyes blazed red with fury when he searched through the seams on the clothes. I recall when he found a small image of Our Lady of perpetual Help on Iryna Vovk-Kulchytska (and she cherished it like the most precious treasure throughout the entire investigation), he turned mad and hurled it down and stamped on it. We faced a sadist, dreadful and vile. We were all indignant but there was nothing we could do: it was the prison. Each of us has already undergone the difficult investigation procedure. Our bodies were exhausted in the dark dungeons, and that hunger strike undermined our health even more. Three or four days later, I was not even able to get up from bed for the head-check. Others did not feel well, either. Some women had a fever. Having to stand all day was especially unbearable. In order to survive that torture, we leaned on each other, shoulder to shoulder, like the geese. During the morning head-check, Liuda announced she was not able to get up from her bed any more, and others had a fever. Eventually, in the end of the day, they brought us some tepid coffee, for the first time in a long time. Men also joined our hunger strike, to express their solidarity. Prison authorities had to give in.

Fordon, a women’s prison

We were brought to Fordon. Everyone made it here, except for Iryna Vovk who stayed in a hospital in Grudziadz, after a complicated surgery.

Fordon is a well-known women’s prison from before the war. They brought here women from all over Poland. For three days, they were taking us outside, to the yard, to fill in the mattresses with the straw. It was a large yard with stacks of straw and many female inmates.

And there it happened…

Here, I met my mother. No one punished us here, no one separated us. We were sitting next to each other and sharing what happened. We were happy to be alive and to stay together. After three days of the quarantine, the newly arrived inmates were sorted and allocated to small and big cells. We were put on the ground floor in a large cell, for almost 40 inmates, with political prisoners, both Poles and Ukrainians. Men were found only among the prison staff. Small cells usually had more dangerous inmates. They were not allowed to work. Those cells were located in the basements, in the cellars. They had inmates with long terms and under strict regiment. As far as I know, there were also some of our girls: Iryna Tymochko “Khrystia”, Liuda Kot “Burlachka”, Katrusia Kosarevych “Nina”, Lesia Lebedovych “Zahrava”, Stefa Onyshkevych (wife of “Orest”), Liuba Bohachevska, Zenia Datsko, Maria Huk, Yevhenia Vakhnianyn-Sukhoronchak, Stefa Kunytska-Bodnar, and others. The others worked in various workshops or in the prison’s general services. We found work extremely necessary for us, especially when we did not have any help from families. Thanks to it, we could earn something, and the time went by faster. Some of the earnings was spent for living, and some money was deposited to the “hard” account. After release, inmates could use the money for their travel expenses. The remaining money could be used to buy some small things in the prison’s canteen. There, you could buy some food stuff (fat, sugar), soap, toothpaste, and the like. We could also help those inmates who were not receiving anything, and who had it extremely hard.

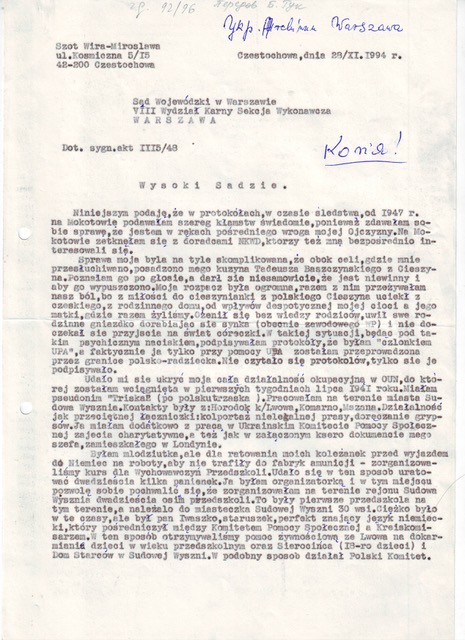

Kateryna Vitko-Stakh’s excerpt is from a book of recollections of women who were members of the Ukrainian underground in the immediate postwar years, collected by Maria Pankiv in the 1990s. Pankiv is a journalist and member of the Ukrainian minority that has lived in Warsaw, Poland, since the 1990s. In those years, she worked for “Slovo,” a Ukrainian Archive in Warsaw. She interviewed a number of women who had been arrested in Poland for their involvement in the Ukrainian underground. Based on these conversations, she composed two volumes of their recollections. The chosen fragments reveal a story of Vitko-Stakh (liaison of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army under the pseudonym “Zozulya”) about her childhood, the beginning of the Second World War, life on the brink of Nazism and Communism, the autumn of 1944, the NKVD’s search for her, and her arrest. She received a sentence of ten years and was held in prisons in Rzeszów and Tarnów. In the presented fragments, you will find Vitko-Stakh’s memories on her family and life before the war, war, her prison experience, interrogations by the Polish security service in 1948, hunger strikes, and the power of prayers in prison.