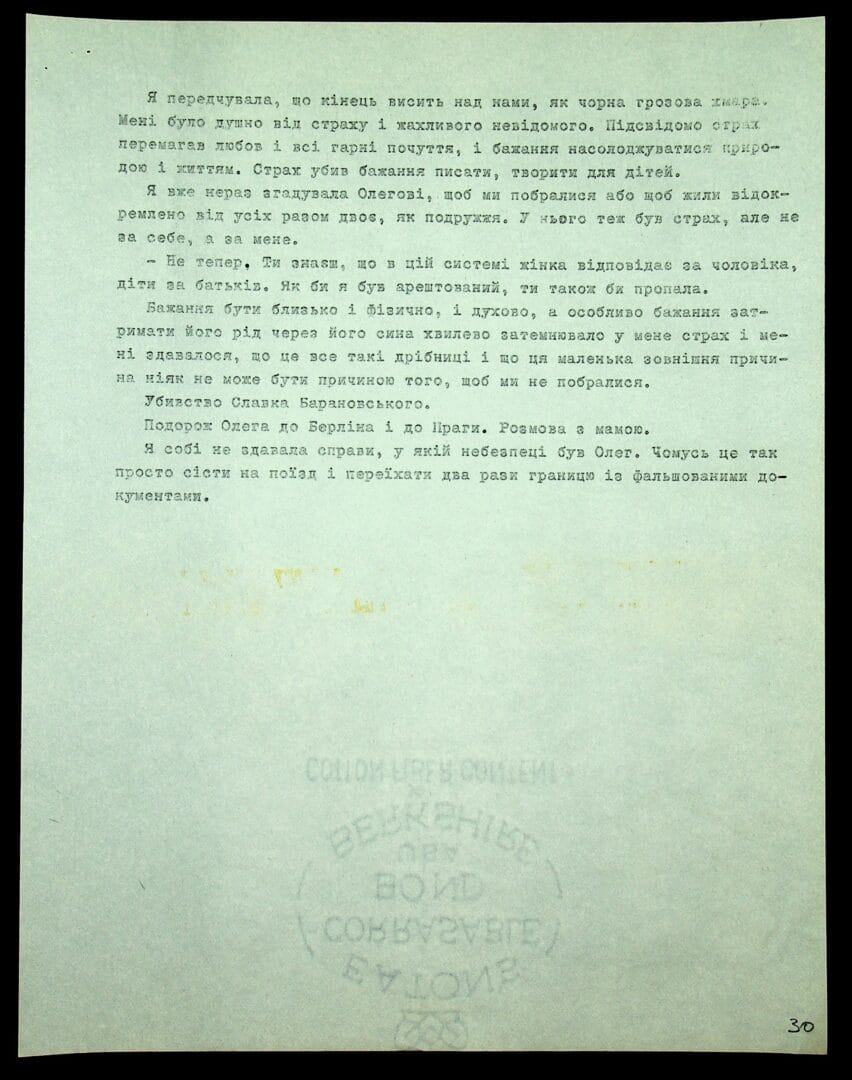

[pp. 29-30]

That room is hard to forget. A narrow bed, almost at the floor – a grid on wooden legs in the form of beams. There is a rug on the wall, with black patterns on it and other black patterns that resemble dried blood. When the curtains are lifted, they look dirty chocolate in the moonlight, and during the day they are bright red.

There are no footsteps, no movement on the street. For some reason, this street, Akademichna, so cheerful and blooming during the day, is so scary and shivering at night.

A gunshot. What happened? Some shadow shoots, some shadow falls and dies. Does it hurt to die? Is it scary?

There is a shadow lying. Where? On Akademichna Street? No, not on this street, farther away. On the paved sidewalk.

Is this how his end will come, on a sidewalk, or maybe in a park on the grass, maybe somewhere in a house, or maybe here, in this room?

Every night you listen to these sounds of the night and try to understand how it will end. This end without ending, night without morning…

When morning comes, you wait. For what? For the night? No, you are waiting for him to come back healthy and alive. As if from a long journey. Tanned. Rich; he’ll bring an abundance of wine and leather.

Write! Works of art! Why don’t you write? The whole day is yours. Today, tomorrow and the day after tomorrow and… No, I can’t. I’m waiting. I’ve been waiting since dawn. The patterns on the rug are becoming clearer. The gladioli are emerging from the corner of the room, like playing a keyboard, they are waiting too. Listen – the birds are singing. It is incredible, they sing with the wind, with clarity, with faith. The first chimes are chasing the expectation far, far away. It’s easier to wait, the night is over.

The pillow fell to the ground. Oleh’s pillow is clean and white near the wall. His nightgown is wrinkled, but it’s the one I sewed in Prague. It is also white, and its waiting was rewarded. Lionia [an unidentified person. – O. P-Ts.] gave me a blue robe. “You are my blue swan… You are my blue swan…” And you are my white swan. You come like a white swan and go away, always white. You are so white and courageous and fragile.

I had a feeling that the end was looming over us like a black storm cloud. I was suffocated with fear and the terrible unknown. Subconsciously, fear overcame love and all good feelings, and the desire to enjoy nature and life. Fear killed the desire to write, to create for children.

I had repeatedly mentioned to Oleh that we should get married or that we should live together on our own, as a couple. He was also afraid, but not for himself, but for me.

“Not now; you know that in this system a woman is responsible for her husband, children for their parents. If I were arrested, you would be gone too.”

The desire to be close both physically and spiritually, and especially the desire to maintain his lineage through his son eclipsed my fear for a moment, and it seemed to me that it was all such a trifle and that this small external reason could not be the reason why we did not get married.

The murder of Slavko Baranovskyi.

Oleh’s trip to Berlin and Prague. The conversation with his mother.

I did not realize the danger Oleh was in. Isn’t that easy, to take a train and cross the border twice with fake documents.

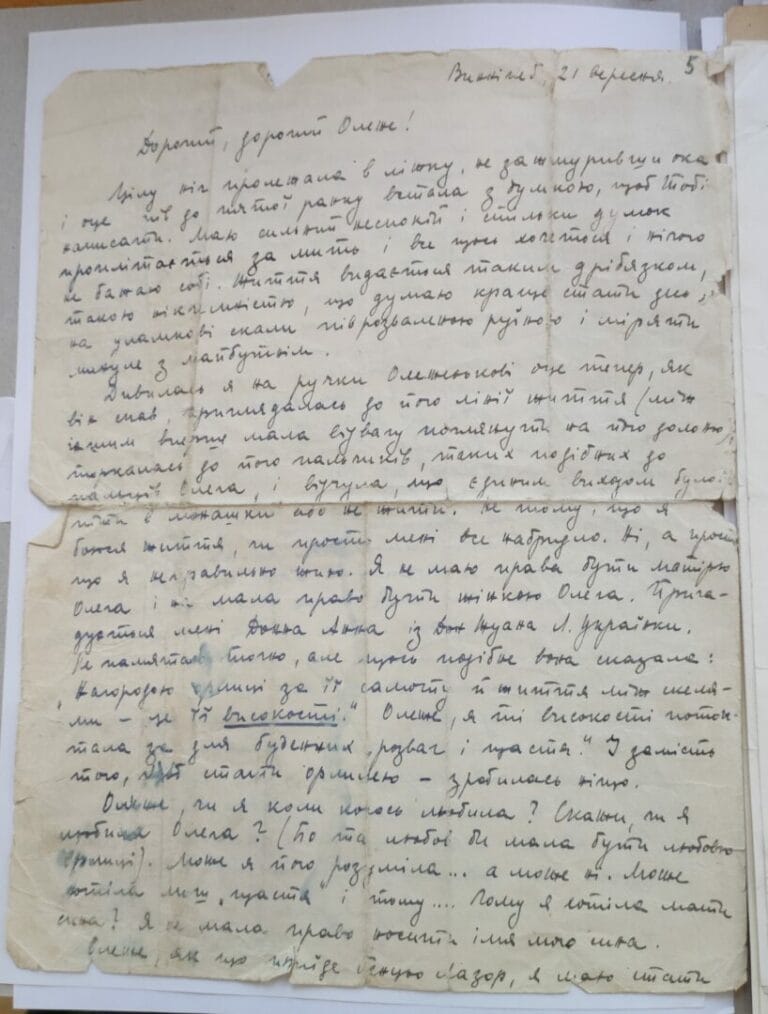

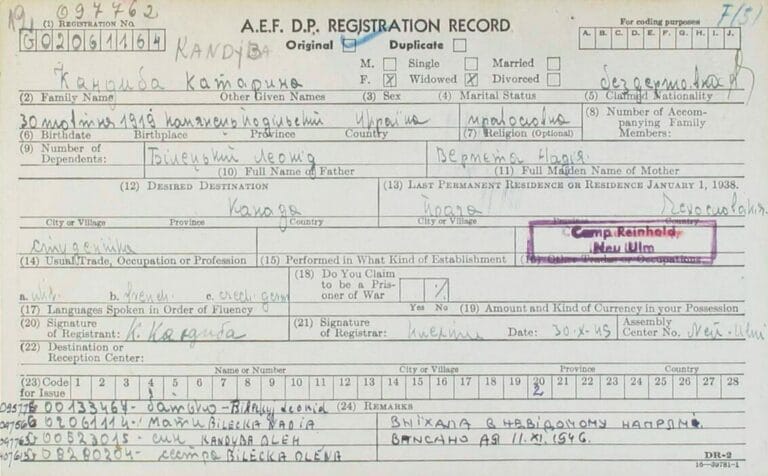

Kateryna Biletska (Kandyba by her first husband), the wife of Oleh Kandyba (known by the literary pseudonym Oleh Olzhych), a poet and member of the Ukrainian nationalist underground, head of the cultural and educational department of the Provid (Leadership) of Ukrainian Nationalists (PUN) and the Revolutionary Tribunal of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) (1939-1941), wrote her memoirs for decades. She first mentions the idea of writing a memoir in letters to a mutual friend of the Kandybas since the 1950s, Oleh Lashchenko. One of the last surviving memoirs is dated May 1994. She sent some of her memoirs to Lashchenko and wrote that she had more. These memoirs mainly cover the years 1940-1944, from their acquaintance with Olzhych to his death in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in 1944, and the Prague and Lviv periods. The memoirs focus primarily on the author’s inner experiences. Two memoirs were published in 1985 and 1991, while the rest, including the one below, have never been published. Some memoirs have been preserved in manuscript and printed versions with certain changes that allow us to trace the movement of the author’s thoughts.

The following memoir describes her life in Lviv in 1943. The text mentions the murder of Yaroslav Baranovskyi, an active member of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists. On May 11, 1943, he was shot dead at the corner of modern-day Vakarchuk and Ustyianovych streets in Lviv. Baranovskyi died under mysterious circumstances, just as Omelian Senyk-Hrybivskyi and Mykola Stsiborskyi, the founders of the OUN, did in 1941. Andrii Melnyk’s followers accused Stepan Bandera’s supporters of these murders. Some researchers suggest the involvement of the NKVD in these murders. After the murder of Yaroslav Baranovskyi, the OUN regional provid issued a statement condemning individual terror as a means of political struggle.