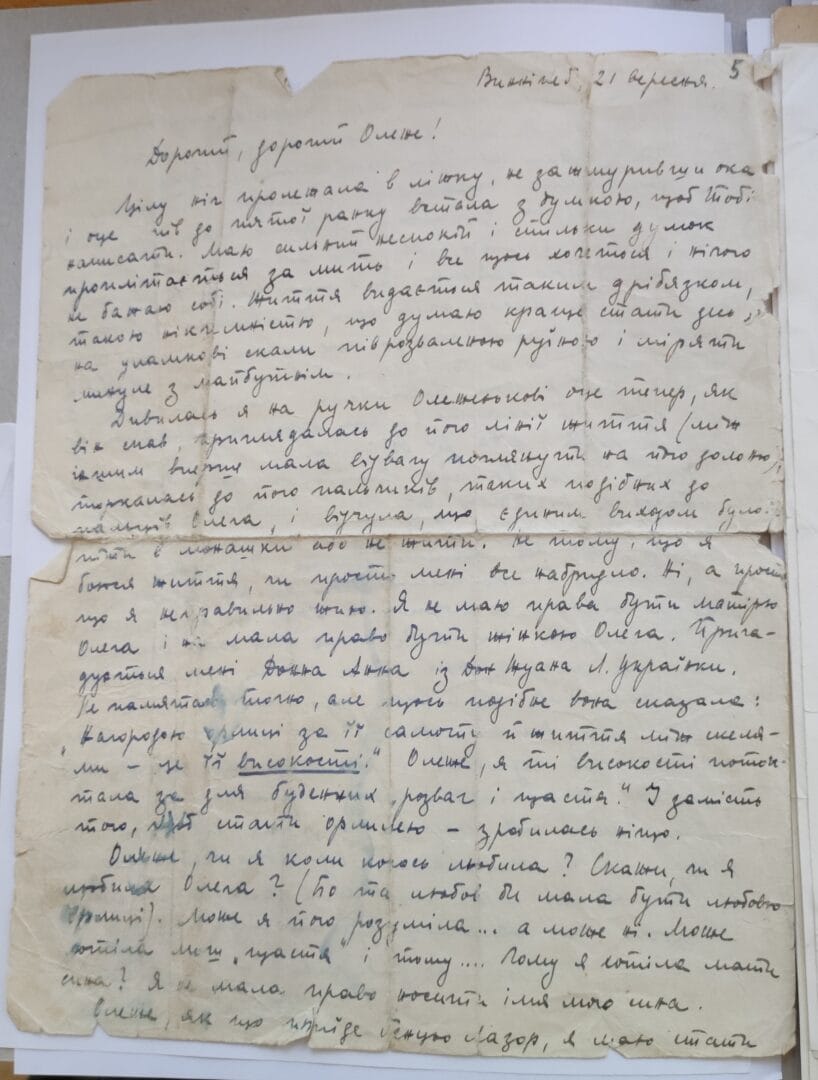

Winnipeg, September 21, 1950

Dear, dear Oleh!

I stayed in bed all night and couldn’t fall asleep, and at 5.30 in the morning I got up intending to write to You. I am very anxious, and so many thoughts are running through my mind, and I always wish something and do not want anything for myself. Life seems so trivial, so insignificant that I think it’s better to stand somewhere on a rock fragment as a run-down ruin, and measure the past with the future.

I looked at Oleh’s hands now while he was sleeping, looked at his lifeline (by the way, for the first time I had the courage to look at his palm), touched his fingers, which were so similar to Oleh’s, and felt that the only solution was to become a nun or not to live. Not because I am scared to live, or just fed up with everything. No, but simply because I don’t live the right way. I have no right to be Oleh’s mother and I had no right to be Oleh’s wife. I remember Donna Anna from Don Juan by Lesia Ukrainka. I don’t remember exactly, but she said something similar to this: “The eagle’s reward for her solitude and life among the rocks is her sublimity.” Oleh, I trod down that sublimity for the sake of routine “entertainment and happiness.” Instead of an eagle, I became nothing.

Oleh, did I ever love anyone? Tell me, did I love Oleh? (Because that love should have been the love of an eagle). Probably I understood him… probably not. Probably I only wanted “happiness” and that’s why… Why did I want to have a son? I had no right to bear my son’s name.

Oleh, if Gentsio[1] Lazor comes, I have to become his wife. The eagle wouldn’t do that, would she?

It’s so dirty when the body prevails over the spirit.

Oleh, what do You think about that?

Will You ever come here… Why do I look for excuses and advice so helplessly? You know, I’m scared to meet Oleh. I’m scared of the other world.

And, Oleh, I have a son. His head smells exactly like his father’s. Am I entitled to raise him? Sometimes I spank him when he is naughty, and he cries and stretches his hands out to me in tears: “Mommy, I love you so much, I love you very much…” and stretches out to me to kiss him. When he cries, something hardens in me, but I have never cried from great grief, rather from a movie.

Oleh, I miss the day when you came to work with a piece of news from Col. Melnyk. I didn’t cry then either. But I clenched my teeth so firmly that my jaws hurt. And I’m sure that if I had seen Oleh after he died, I probably would have never left him; that doesn’t mean that I would have died too, but I would have dedicated my whole life to him. Though, these are just words. I couldn’t believe it, and neither did I realize; I couldn’t realize the horror that he was gone.

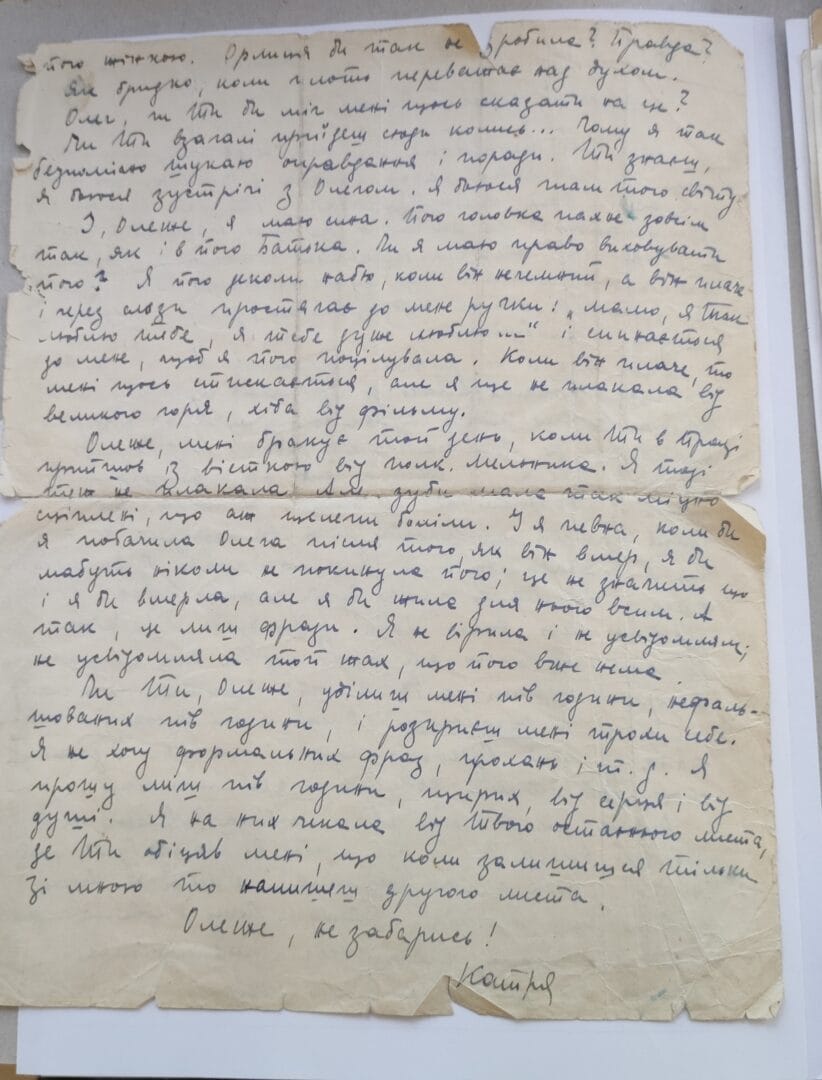

Will you, Oleh, devote me half an hour, not a fake half an hour, and reveal a little bit of yourself to me? I don’t want formal expressions, requests, etc. I ask only for half an hour, a sincere one, from your heart and soul. I’ve been waiting for it since Your last letter, in which you promised me that when you stayed alone with me, you would write a second letter.

Oleh, don’t tarry!

Katria

[1] Affectionate form of the name Yevhen.

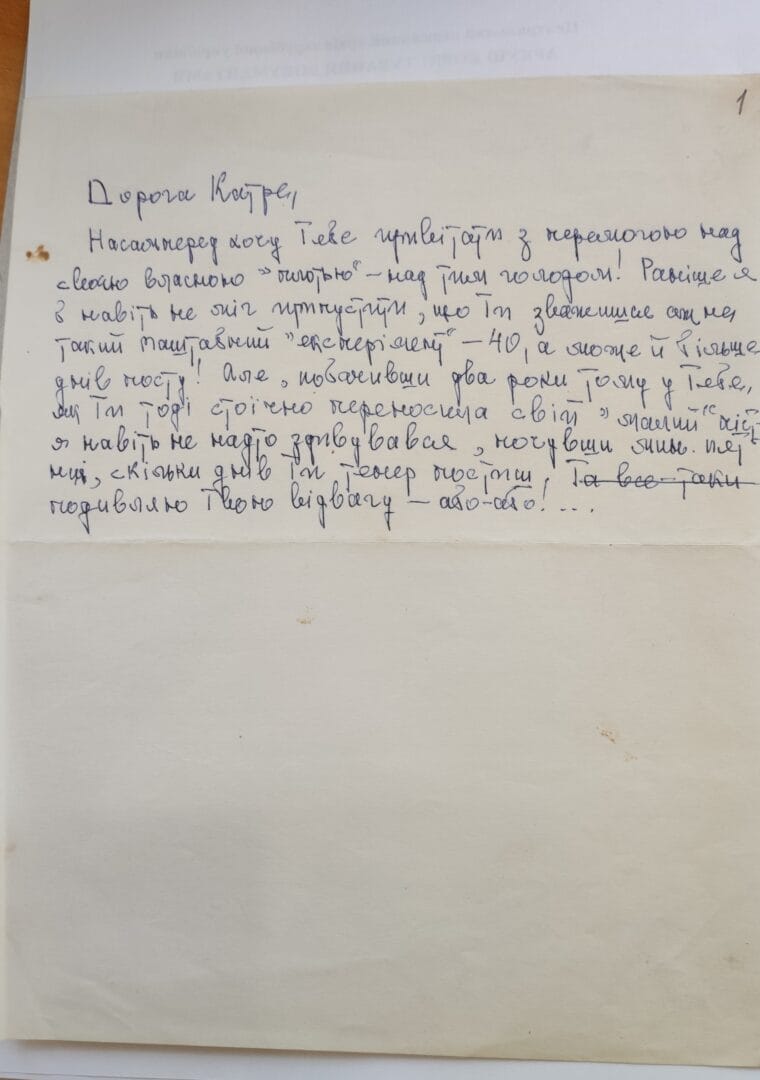

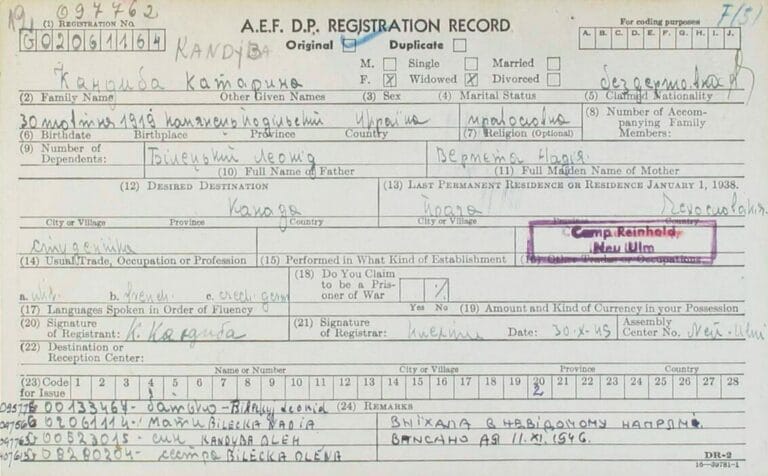

The fund of the Ukrainian publicist and public character Oleh Lashchenko at the Central State Archive of Public Associations of Ukraine contains seven letters and one postcard from Kateryna Biletska (Kandyba by first husband), Oleh Kandyba’s wife (literary pseudonym Oleh Olzhych), a poet and member of the Ukrainian nationalist underground movement, head of the cultural and educational department of the Provid of Ukrainian Nationalists (PUN) and the Revolutionary Tribunal of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN) (1939-1941).

Lashchenko was not only a longtime friend of the Kandybas, but also the godfather of their only son. He was born in Kyiv in 1914, in 1920 he emigrated to Poland with his parents and elder sister Halyna, and in 1921 the family settled in Prague. Lashchenko earned his doctor’s degree at Charles University and joined the OUN in 1935. It was probably at this time that he met Olzhych and Kateryna. In the autumn of 1941, he arrived in Kyiv as part of an OUN march unit, a member of the Ukrainian nationalist underground; he returned to Prague at the end of the year. In 1941, his book Cultural Life in Ukraine was published. After the death of Oleh Olzhych, he headed the cultural and educational department of the Provid of Ukrainian Nationalists. At the end of the war, Oleh Lashchenko left for western Germany, and in 1951 he emigrated to the United States.

The first of the letters quoted here dates back to 1950, as it mentions Biletska’s future marriage to her second husband, the journalist Yevhen Lazor — who wrote feuilletons for the Lviv newspaper Dilo under the pseudonym Yevhen Cherevan, and who worked in the editorial office of the Ukrainian newspaper Volyn during the Second World War — on August 31, 1941, in Rivne, the then capital of the Reichskommissariat Ukraine. Later, Lazor emigrated to Canada and wrote for the magazine Novyi Shliakh (New Way).

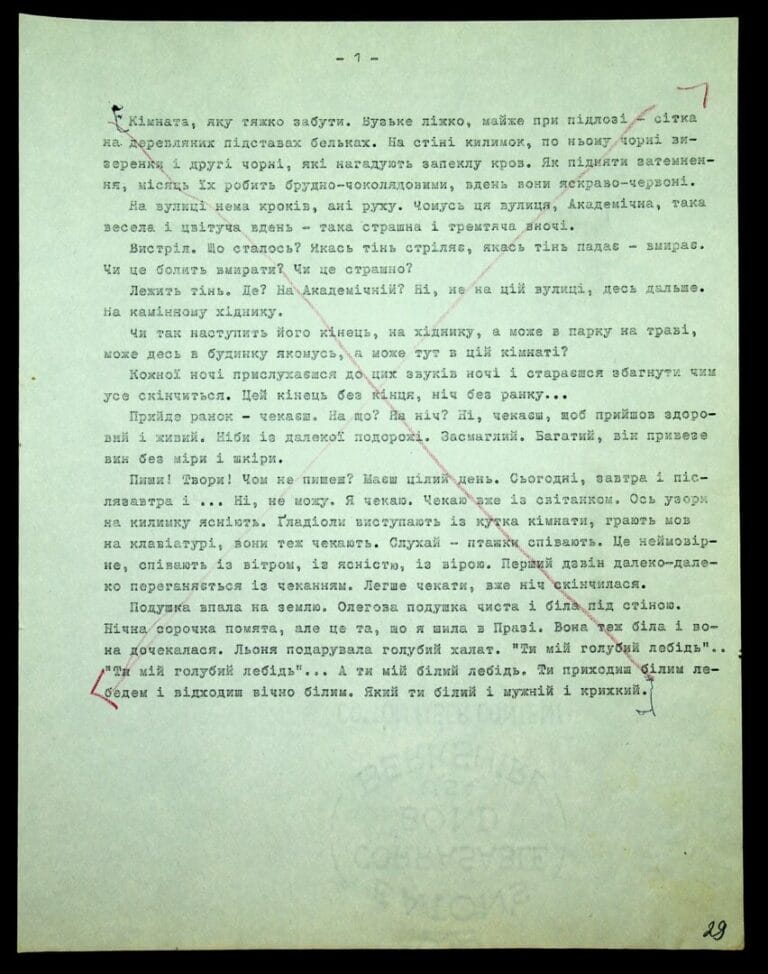

Several key topics can be identified in Biletska’s letters to Lashchenko: admitting depression; evaluations of the cultural environment of Canadian Ukrainians; references to common European experiences; reflections on her relationship with Olzhych; and discussions of the idea of writing a memoir. Biletska reflects on exemplary women. She writes in quotation marks about the “local Ukrainian ‘intelligentsia'”, which she initially assesses critically: “I want to cry or laugh… They wear make-up, their clothes are first-class, but their brains are like a chicken’s. They also speak English with each other. And in general, they hardly understand the Ukrainian language.” She complains about loneliness and lack of empathy: “How can I talk to them, how can I influence them? When they have no interests other than business and money.”

Lashchenko’s letters to Kateryna are more concise. His last letter quoted here was probably never sent.