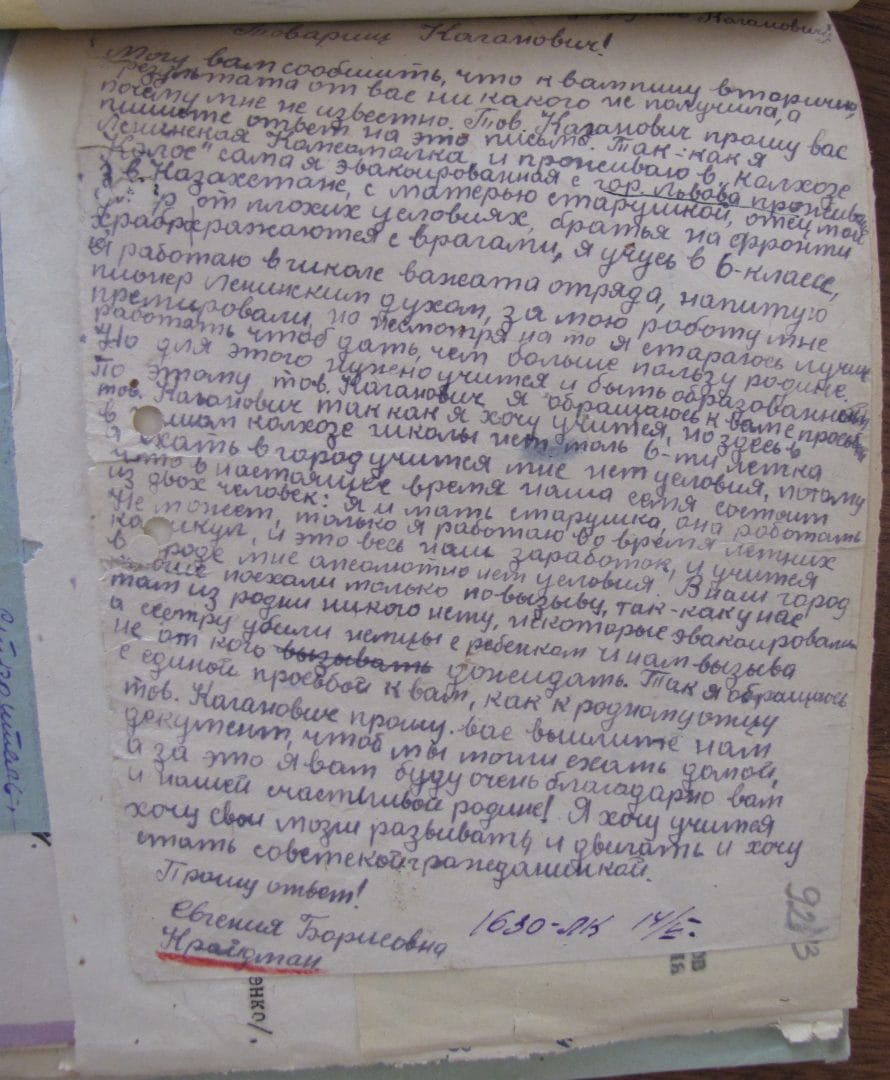

Comrade Kaganovich!

I can inform you that I am writing to you for the second time, I did receive any result from you, and why I do not know. Comrade Kaganovich I beg you to write an answer to this letter. Because I am a Leninskaia Komsomolka [youth communist party] and live in the collective farm [kolkhoz] “Kolos” myself I am evacuated from the city of Lviv and I live in Kazakhstan, with my old mother, my father died from bad conditions, my brothers are fighting with our enemies on the front, I am studying in the 6th grade, I work in school as the leader of our detachment [like their Komsomol group], I fill up the pioneers with the Leninist spirit, they have given me a prize for my work, but despite that I am trying to work to give as much as possible to the motherland. But for that I need to study and to be educated. And so comrade Kaganovich I turn to you with the request Comrade Kaganovich because I want to study, but here in our collective farm there is no school, only a six-year school [i.e., elementary school], but there is no way of going to the city to study, because right now our family consists of two people: me and my old mother, she can’t work, only I am working during the summer vacation, and this is all we earn, and there is just no way I can study in the city. Many people have gone to the city [that is, back to Lviv where she is from] by invitation [by having an invitation letter that shows they are hosted by a person or institution], but because there is no one left from our family, some were evacuated, and the Germans killed my sister with her baby and there is no invitation to (to invite crossed-out) to wait for from anyone. So I am turning to you with one request, as to my own father Comrade Kaganovich I beg you to send us the document so that we can go home, and for that I will be very grateful to you and to our happy motherland! I want to study I want my brains to develop and to move and I want to become a Soviet citizen.

I beg for an answer!

Evgenia Borisovna

Kraidman (red underline)

This letter comes from a collection of individual inquiries sent to the Lviv Executive Committee and the Temporary Governmental Commission for Entrance into Lviv between summer 1944 and spring 1945 and kept in the State Archive of Lviv Region – DALO. This and other letters can be read in at least three larger contexts: massive mobility and displacement brought by the Second World War across the entire European continent, both as a part of war and as a part of postwar settlement; attempts by individuals to find home or a place of residence in the context of anticipated postwar; and a particular role of letter writing in citizen-state relationship. More specifically, the contexts of the Soviet state and the city of Lviv have to be taken into account. The Soviet authorities were actively using various regulatory, security, and violence tools in this process, from granting or not residence permits to so-called “transfers of populations” across new borders, and forcibly resettling entire ethnic groups, like Chechens, Crimean Tatars, and Ingush. The city of Lviv was a new place for the Soviet authorities, annexed from the Polish Republic after the outbreak of the war in 1939 together with other territories stretching from Finland to Romania. Between 1939-44 the city went through Soviet and Nazi occupation, which diminished its inhabitants more than in half, while leaving few physical destructions. In the last days of July 1944, the city was taken by the Red Army and incorporated into Soviet Ukraine as a part of the Soviet Union. Following years saw massive displacement of Polish Lvivians and influx of people from the surrounding regions, the Soviet Ukraine and the entire Soviet Union.

The present source is a letter Evgenia Kraidman wrote to Lazar Kaganovich, a top Soviet official. Yet, it was redirected to the Temporary Commission for the Entrance in Lviv, a city she saw as her desired destination. Hers is one of several hundred letters preserved in this archival collection and her second attempt to reach Kaganovich. In other words, she is engaged in a process of communicating with authorities by petitioning her case and there are many people doing the same. While not unique to the Soviet context, such communication was a central element in shaping the relationship between the state and citizens and fashioning both Soviet statehood and Soviet self. Writing letters to authorities was not only an activity for adults. Children were writing letters as a part of their school and extracurricular education, often supervised by adults – teachers or relatives. Among numerous corpus of letters those written during and right after the war stand out as an instrument of coming with the war traumas, as a means to show brutality and educate vengeance, as well as a bridge between war experiences and anticipated post-war life.

There are a couple of insights in a close reading. As many letters written during the time of war, this one utilizes what was available at hand – a half of the A4 page, probably taken out of a notebook. Clear handwriting and self-description as a pupil of the 6th grade, reveal that Eugenia is a teenager between 12 and 14 years old. Belonging to “Lenin Komsomol” is a bit confusing as 6th- graders were not yet accepted to the Komsomol. However, it might be the case that her age and her grade did not align, given the context of war and evacuation (or deportation). She has sent her letter from Kazakhstan, a residency which could testify for both. She clearly indicates the reason for her and her mother to be in Kazakhstan and more specifically in kolkhoz “Kolos” („Ear”) – evacuation. In doing so she places herself in a cohort of people loyal to the Soviet state, who went to evacuation and did not stay under Nazi occupation. Furthermore, she distances herself and her mother from a cohort of people who were “deported” to Kazakhstan, especially from Lviv and the surrounding regions annexed into the Soviet state in 1939-40. Evgenia clearly wants to be in the cohort of evacuated citizens, not deported.

Presenting the proper past was a prerequisite for a better future. Evgenia uses the word “happy” to describe the Soviet state as “happy Soviet homeland.” Describing her personal and family hardship – lack of money, poor health of her mother, killed relatives – she constructs an image that runs contrary to the image of “happy childhood” promoted by the state and from this point of hardship comes her plea for the better future – as a part of Soviet polity. She leans forward and inscribes herself as a part of it, where she “could develop and move her brains to become a Soviet citizen” conflating her personal trajectory with the one of the “happy Soviet homeland.”

In the letter she uses “our home town” without providing a specific address, but refers to it as. Two options are possible here: either Lviv became a place of residence for her and her family between 1939 and 1941, when the city was annexed into the Soviet state and integrated into Soviet Ukraine. Or, it was a place where she was born or/and lived before 1939. Her letter is written in Russian, which supports the possibility that she came to Lviv with her family between 1939-41. Yet given that she had several years of education in a Soviet school in Kazakhstan and her Russian comes with numerous mistakes, the possibility that her family resided in Lviv before 1939 can not be ruled out entirely. She does not dwell on the past, but emphasizes that Lviv is first of all a city, where she can study “to be educated” and thus “to serve motherland.” In other words, she sees Lviv as a place where she expected to find education, work, and housing, key elements of moving on from war and shaping post-war life.

Evgenia writes on behalf of herself and her mother. The content and the language of her letter tell a story of a teenager, but her signature is adult. She uses a full form – name, patronymic, and surname (Evgenia Borisovna Kraidman). This can be a sign of respect and officialness. After all, she addresses a very powerful person. But it also can be a sign of taking up a role of adult in the family, with her brothers on the front, her father dead, her sister killed and her mother sick. Whatever the family situation is, there are high chances that war and life in evacuation had a toll on her family as it did on many others.

Finishing with the very last word of the letter. Evgenia’s surname “Kraidman” gets red underlining at some instance in some official office. Is it a note that her family is a Jewish and what it implies? The passage about her sister and her baby killed by the Nazis support this version. Moreover by 1941 the anti-Jewish policies were known even if the scale was still to be revealed. Hence comes one more reason to evacuate. Or maybe her family was deported? In 1940-41, the waves of Soviet deportations from western Ukraine included well-to-do Jewish inhabitants and Jewish refugees. What we know is that there was nobody from relatives in Lviv who could send a formal request to come (vyzov), as she points out. Thus, it was in the power of authorities to give her permission to travel to Lviv for which she asked and hoped.