January 6, 1909, Wednesday

It is the evening of the Holy Supper. The weather is mild outside, with a slight drizzle and some wind. I sent Christmas cards to Slavko and Melania,[1] the Borodievychs, the Horodyskis, Theodore (Feds), my nephew in Stryi, the Tysovetskis, and the Listovetskis.

Mania (Maria Hrushkevych, ICh) arrived from the post office at 8 o’clock. Even on Christmas Day, she needs to go to the bureau at half-past seven as usual, and then she has Thursday and Friday off.

We gathered for dinner with my wife, Ivan, Zosia, Mania, Myroslav, and myself. In the kitchen were also gathered Maria Linchak, the head maid, Lisa B…(who follows the Latin rite), Maria’s aunt Piekarska, and her son Fransio (a boy from the third public school[2]). The atmosphere at dinner was jovial. Especially Granson seemed delighted, devouring almost everything except the fish (although the next day he was a bit hesitant). We upheld our old-world traditions of feasting and merriment. All of us drank a bit of alcoholic—wine and vodka—except for me and Grandson. The menu was the following (noting to remember): borshch with vushka,[3] fish stew, holubtsi[4] with porridge, fried fish, apple strudel, kutia,[5] oranges, and nuts. Except for wine and vodka (beer and vodka in the kitchen), tea was served towards the end of the meal. I only drank tea. After our dinner, we sang carols in this good company near the Christmas tree, laden with various treats, much to Grandson’s delight.

April 11, 1909, Sunday

The weather is chilly outside. I headed to the Voloska church early at 9 o’clock, catching the tail end of the Divine Liturgy. Communion was being served. Inside, I encountered my friend Koles Lev, pan[6] Revakovych, pan Pidlasheckiv, pan Pollnuk (illegible, ICh), Turchmanovych, and Onyshkevych. Afterward, I returned home and remained indoors until noon. We had breakfast and waited with Easter eggs for Mania, who was alone at the post office; it wasn’t until nearly quarter past two that we finally fetched her. We all shared the blessed eggs together, including our immediate family. There was no distinction in the ritual, as it was also the time of Latin Easter. So, my wife as well participated, and we all celebrated: my wife, Slavko and his wife, Zosia and her husband, Mania, and myself. My son-in-law tends to see to these customs in what some might deem less formal attire—without a jacket and tie. It’s becoming less common to follow holiday rituals, though perhaps someday it will be the norm; for now, it still remains surprising. I dined the blessed food with my maid Marynia and Slavko’s maid, who came to look after the kid.

We departed at 4 o’clock in the afternoon. Slavko and his wife, followed by Zosia and Ivan, headed to the Revakovychs.[7] The two of us elderly folks remained with the grandchildren and Tarasko’s[8] nanny. Later in the evening, around 9 o’clock, the Revakovychs sent a maid to escort us elderly folks to their home. Our children had already returned home. While Slavko, Melania, and Mania went to Urania,[9] Zosia and Ivan stayed home, and we elderly folks accepted the invitation…

Notes:

[1] Yaroslav and Melania Hrushkewych (formerly Borodiyevych), the son and daughter-in-law of Hrushkewych, residing in Ternopil during that period.

[2] A primary school, then called a “people’s school” (pol. szkola ludowa).

[3] Small dumplings, usually filled with flavorful wild forest mushrooms and/or minced meat.

[4] Cabbage rolls, stuffed with pork and rice or porridge.

[5] A ceremonial grain sweet dish, served mostly by Eastern Orthodox Christians and some Catholic Christians.

[6] Slavic honorifics in Poland and Ukraine.

[7] The family of Titus Revakovych, a founding member of Shevchenko Scientific Society, legal advisor to the Prosvita Society, chairman of the St. Raphael Society for Emigrants, and co-editor of the Ukrainian magazine Zoria.

[8] Another grandson of the Hrushkewyches, the son of Yaroslav and and Melania Hrushkewych.

[9] A branch of the Vienna-based Urania film studio, which began its work in Lviv in 1901.

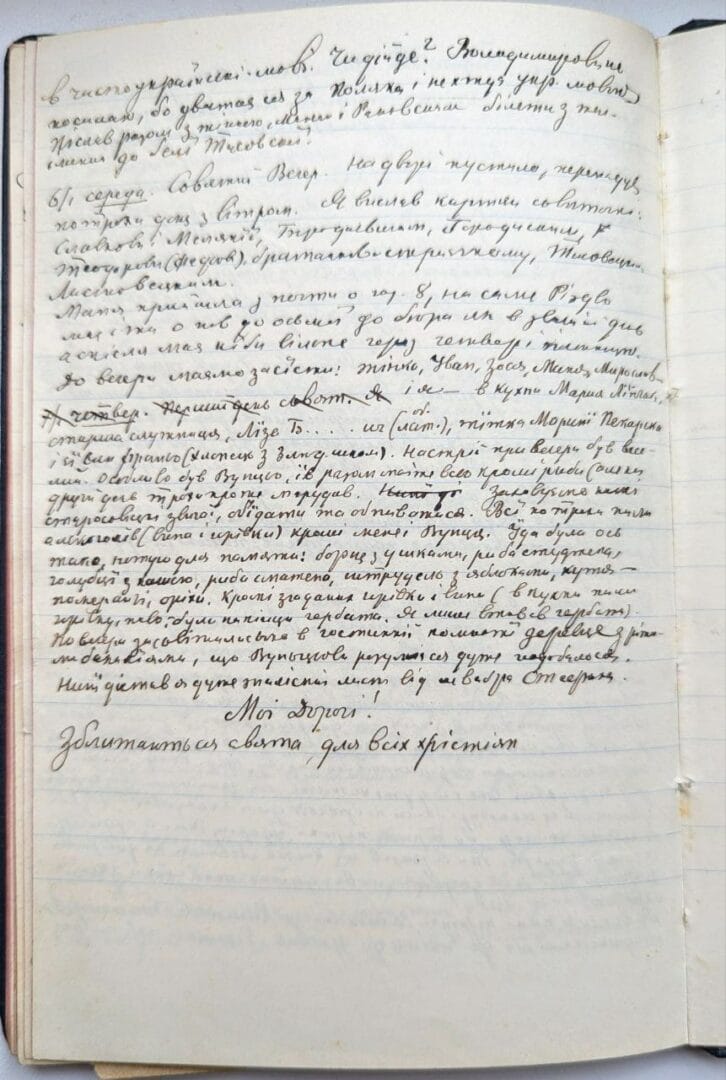

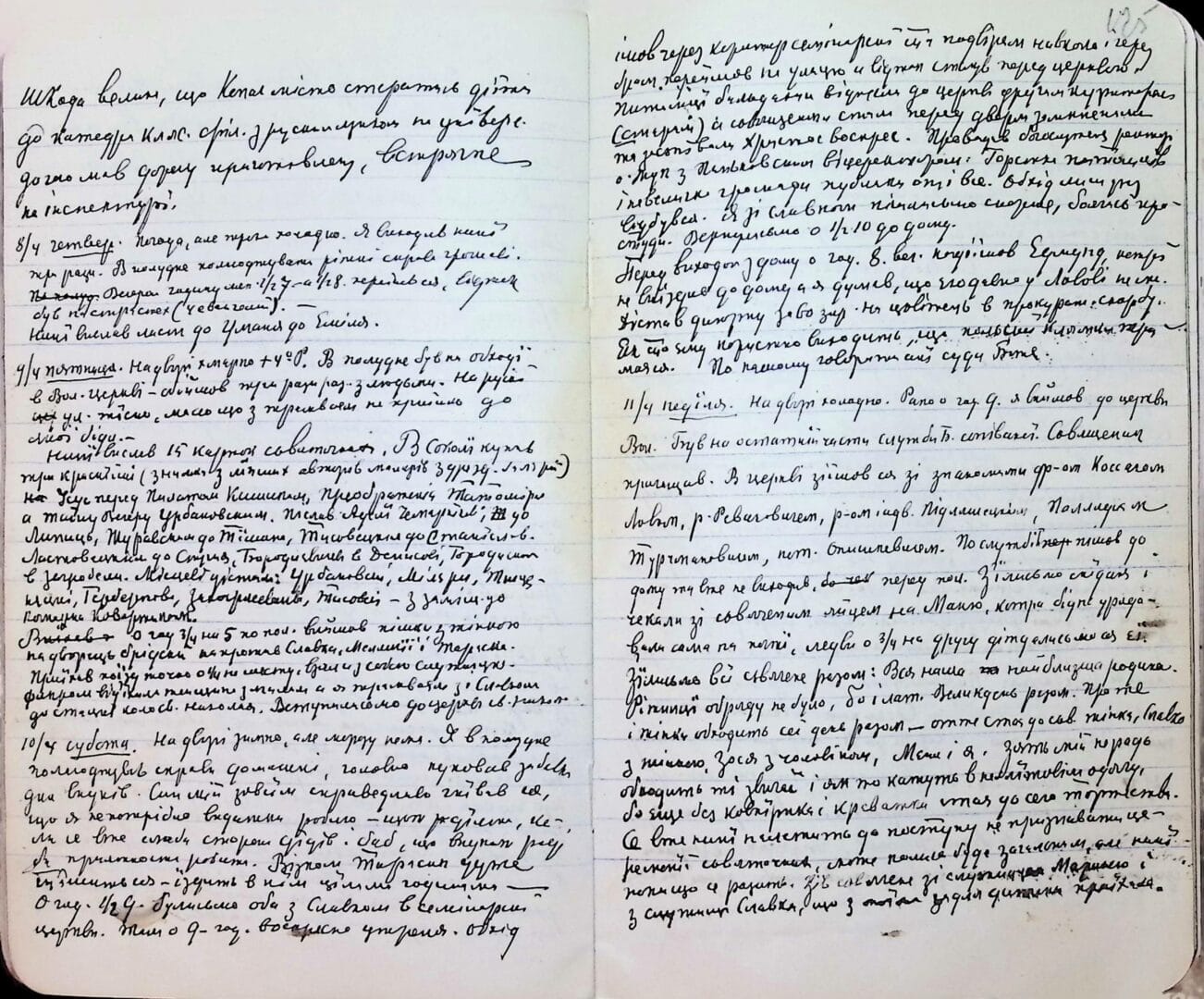

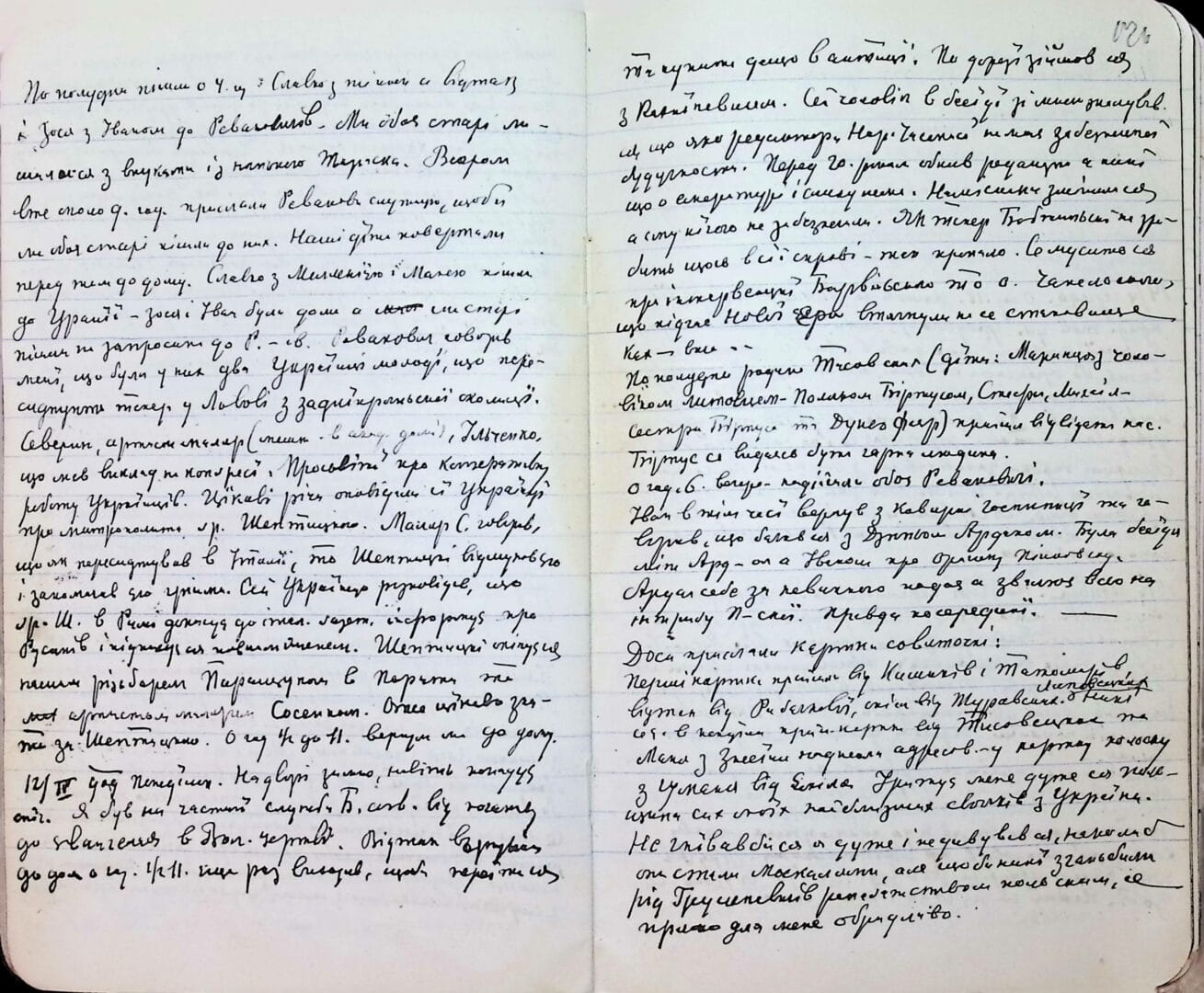

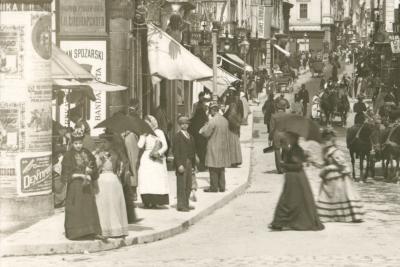

Teofil Hrushkevych a teacher of classical languages at the Second (German) Gymnasium in Lviv, commenced his diary in 1895, though it was only after his retirement in 1906 that his entries became regular. The extant handwritten diary comprises eight notebooks, documenting entries for 1895, 1903, and 1906 (intermittent), and for 1908-1915 (almost daily). Typically, the author penned his notes in the evening, commencing with a depiction of the weather, followed by an account of the day’s events: personal matters, such as receiving a pension, settling bills, visiting friends or acquaintances, attending church services, and social engagements, such as participating in meetings of Ukrainian societies to which he belonged, attending the theatre or a concert, and engaging in electoral activities, among others.

One of the most frequently mentioned individuals in his notes was his immediate family: his wife, Liudmyla, and his youngest daughter, Maria, who worked as a postal worker in Znesinnia (then a nearby suburb of Lviv, now integrated into the city). At the time of writing, his older married daughter, Sofia, along with her husband, Ivan Rakovskyi, and their young son, Hrushkevych’s grandson Myroslav, resided with him.

Other inhabitants of his household, specifically domestic servants, also featured prominently in Hrushkevych’s writings. By 1908, Maria Linchak, affectionately referred to as Marynia by the Hrushkevyches was employed as a servant in their home. Marynia remained in the service of the Hrushkevyches for approximately three years. Additionally, another girl named Lisa worked in the household as a nanny for their grandson.

The Hrushkevych family observed the major Christian holidays in accordance with both the Julian and Gregorian religious calendars. Theofil Hrushkevych hailed from a lineage of Greek Catholic priests, while his wife, Liudmyla, originated from an Armenian, possibly Armenian-Jewish background, and adhered to the Roman Catholic faith. Despite their differing religious affiliations, private correspondence within the family attests that these differences never led to misunderstandings between the couple. Liudmyla regularly went to her church (Pol. kościół), just as Theofil – to his; she corresponded with their children in Polish (although the exact language spoken at home remains unclear), while he communicated in Ukrainian. Their family dynamic stood in contrast to the prevailing negative portrayal of mixed marriages (particularly Ukrainian-Polish unions) prevalent in the Ukrainian press and memoir literature of the era, which often depicted such unions as a threat to Ukrainian national interests.