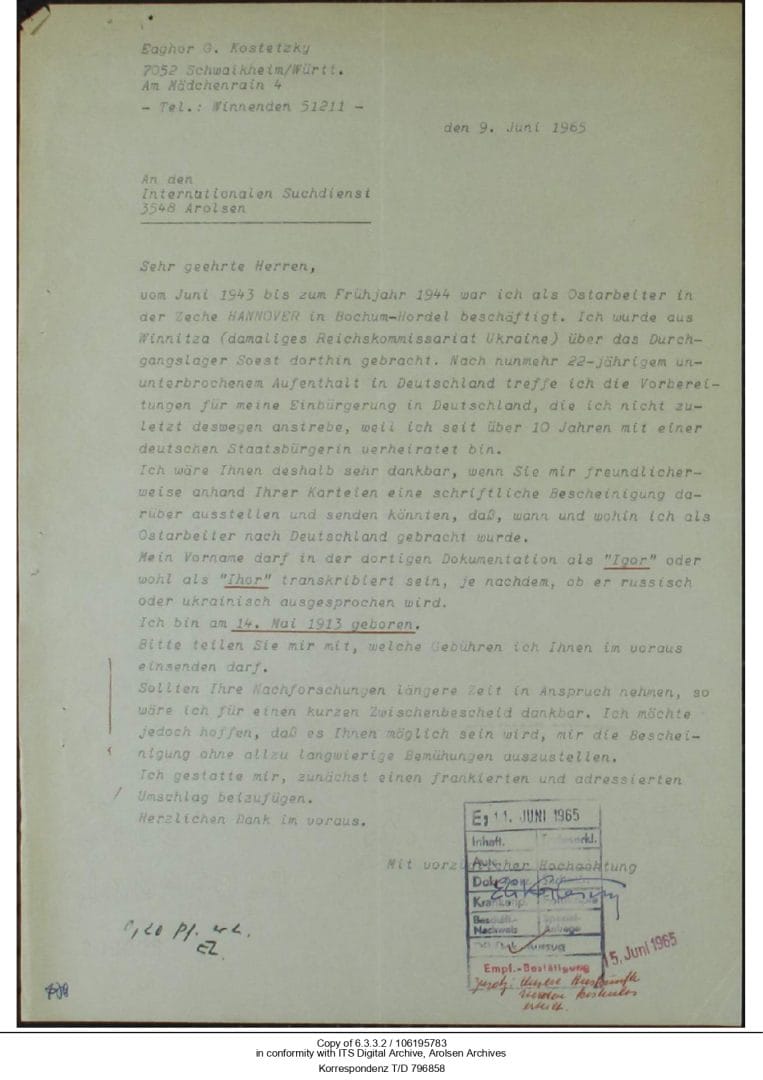

Letter from Kostetskyi to the International Tracing Service

Yegor G. Kostetskyi

7052 Schwaikheim/Württ.

Am Mädchenrain 4

-Tel.: Winnenden 51211

June 9, 1965

To the

International Tracing Service

3548 Arolsen

Dear Sirs,

From June 1943 to early 1944, I was an Ostarbeiter at the HANNOVER colliery in Bochum-Hordel. I was brought there from Winnitza (then Reichskommissariat Ukraine) via the Soest transit camp. After 22 years of uninterrupted residence in Germany, I am now making preparations for my application for citizenship in Germany, which I am seeking, not least because I have been married to a German citizen for over 10 years.

I would therefore be very grateful if you could kindly issue and send me a written certificate based on your files stating when and where I was brought to Germany as an Ostarbeiter.

The documentation there may transcribe my first name as “Igor” or probably as “Ihor,” depending on whether it is pronounced in Russian or Ukrainian.

I was born on 14 May 1913.

Please let me know what fees I may send you in advance.

Should your research take longer, I would be grateful for a brief interim reply. I hope, however, that you will be able to issue me with the certificate without too lengthy an effort.

Please allow me to enclose a stamped, self-addressed envelope.

Thank you very much in advance.

With the highest consideration

EG Kostetzky

In original German

Eaghor G. Kostetzky

7052 Schwaikheim/Württ.

Am Mädchenrain 4

-Tel.: Winnenden 51211

den 9. Juni 1965

An den

Internationalen Suchdienst

3548 Arolsen

Sehr geehrte Herren,

vom Juni 1943 bis zum Frühjahr 1944 war ich als Ostarbeiter in der Zeche HANNOVER in Bochum-Hordel beschäftigt. Ich wurde aus Winnitza (damaliges Reichskommissariat Ukraine) über das Durchgangslager Soest dorthin gebracht. Nach nunmehr 22-jährigem ununterbrochenem Aufenthalt in Deutschland treffe ich die Vorbereitungen für meine Einbürgerung in Deutschland, die ich nicht zuletzt deswegen anstrebe, weil ich seit über 10 Jahren mit einer deutschen Staatsbürgerin verheiratet bin.

Ich wäre Ihnen deshalb sehr dankbar, wenn Sie mir freundlicherweise anhand Ihrer Karteien eine schriftliche Bescheinigung darüber ausstellen und senden könnten, daß, wann und wohin ich als Ostarbeiter nach Deutschland gebracht wurde.

Mein Vorname darf in der dortigen Dokumentation als „Igor“ oder wohl als „Ihor“ transkribiert sein, je nachdem, ob er russisch oder ukrainisch ausgesprochen wird.

Ich bin am 14. Mai 1913 geboren.

Bitte teilen Sie mir mit, welche Gebühren ich Ihnen im voraus einsenden darf.

Sollten Ihre Nachforschungen längere Zeit in Anspruch nehmen, so wäre ich für einen kurzen Zwischenbescheid dankbar. Ich möchte jedoch hoffen, daß es Ihnen möglich sein wird, mir die Bescheinigung ohne allzu langwierige Bemühungen auszustellen.

Ich erlaube mir, zunächst einen frankierten und adressierten Umschlag beizufügen.

Herzlichen Dank im voraus.

Mit vorzüglicher Hochachtung

EG Kostetzky

Ihor Kostetskyi was just one example of several several million individuals who were taken by the Nazi Army from occupied eastern European territories and had to work as Ostarbeiter in the German war industry. Before the war, Kostetskyi was involved in several cultural, artistic, and creative projects and initiatives. Born in Kyiv, he made little declaration of his Ukrainianness until Carpathian Ukraine started to seek independence in 1938. When he was mobilized into the Red Army at the start of the German invasion in 1941, he was in the process of changing his real name, Ivan Merzliakov, to the pen name, Ihor Kostetskyi. This is the name he would use in the future. After the German capture of Vinnytsia, Kostetskyi worked as the editor of “Vinnytski Visti,” the German occupation newspaper for the local population.

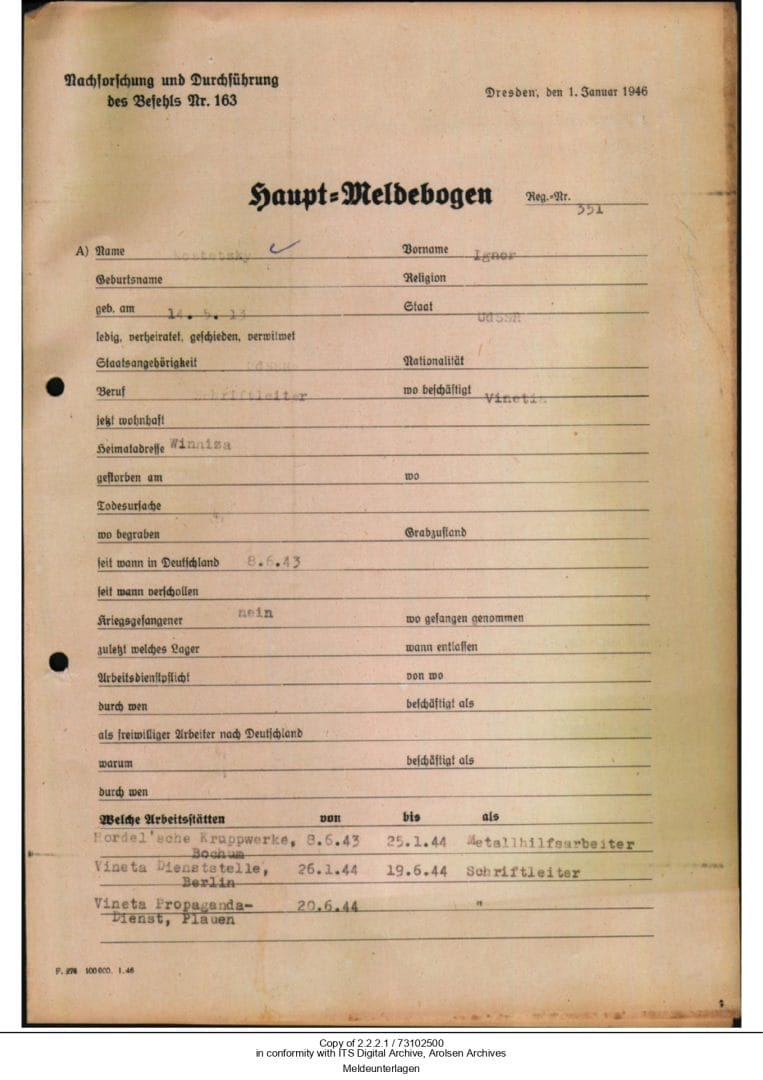

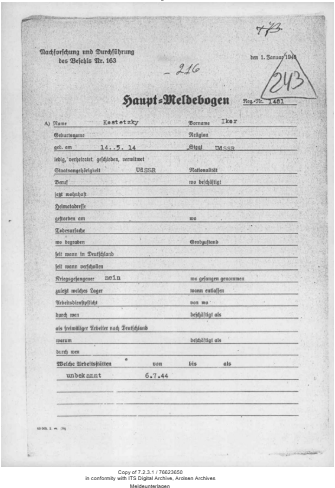

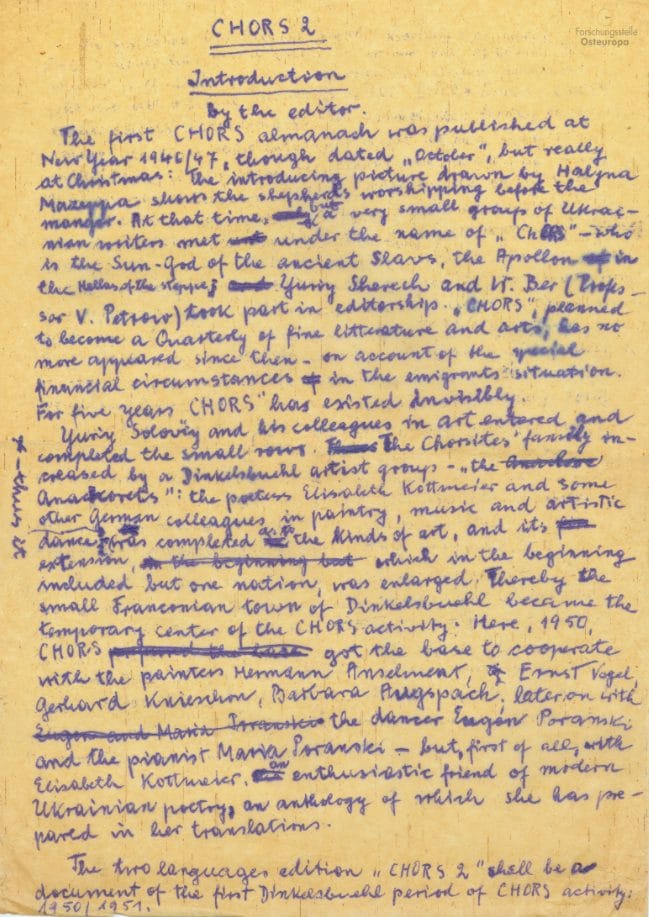

Kostetskyi’s documents, written immediately after the war, nevertheless showed that he was seemingly not a prisoner of war when he was taken from the city of “Winniza” (the authorities meant the Ukrainian city of Vinnytsia) and arrived in Germany on June 8, 1943. According to the historian Marko Robert Stech, Kostetskyi reported himself for duty to prevent his friend from being taken. Via a transit camp in Soest, he was then taken to Bochum to work as an unskilled laborer in the “Hordel’sche Kruppwerke” metal plant. The working conditions were very difficult, and the number of deaths during such work was extremely high. Kostetskyi nevertheless managed to survive. Most likely, his literary experience came in handy again. The Nazi authorities decided to move him away from the hard labor in the metal plant and instead employ him in the “Vineta Propagandadienste,” first in Berlin, then in the city of Plauen. There he was, according to Stech, in a leading position in charge of publishing the German propaganda newspaper “Dozvillja,” which was to be distributed to the other Ostarbeiter in German forced labor camps and plants. He seemingly stopped working at the Vineta office in Plauen on July 6, 1944. At the end of the war, he was in the Bavarian city of Fürth. This prevented him from being forcefully repatriated to the Soviet Union, where he would most likely be imprisoned, deported, or executed because of his sheer service, even though forced, in the apparatus of the German war industry.

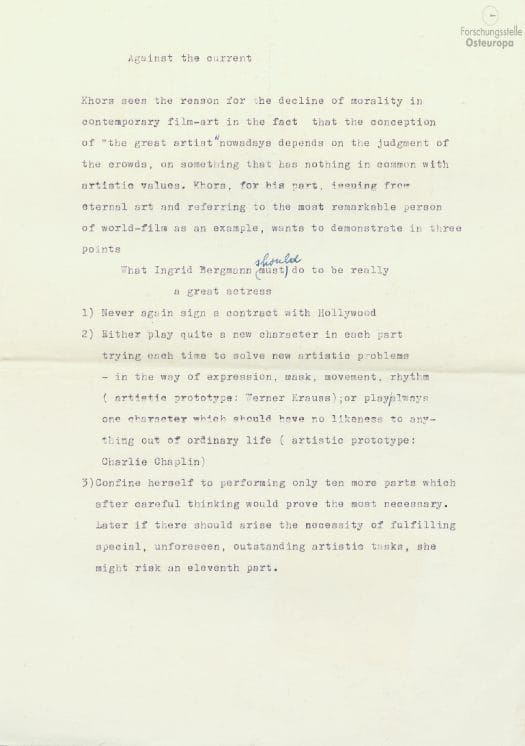

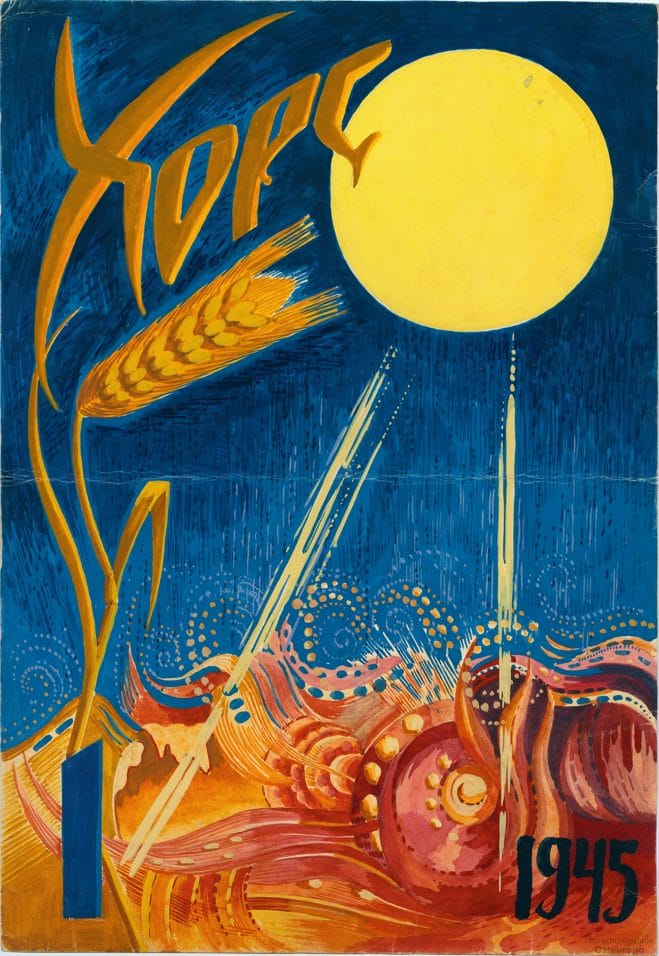

From Fürth, he was sent to one of the Ukrainian DP camps in Bavaria, and began working on the Ukrainian diaspora magazine KHORS. In the letter below, written by Kostetskyi to the Arolsen Archives in 1965, he asked for official confirmation of his past as a forced laborer, as this could help him in the process of applying for German citizenship.