Biletska lives with her son, sister, and parents, but she feels lonely without the social circle that had formed in Prague. “You can imagine how it is for me here, especially without you; because there, in Ulm, although I did not write to you, we somehow always had an opportunity to meet,” she writes to Lashchenko, “and here… a letter falls short!.. I don’t want to write at all, because I know that the day will come when we will pour out our hearts about what was unwritten or unfinished.” These testimonies prompt us to consider the language of trauma and the silent repetition of suffering, to think of trauma as a crisis of language, a crisis of representation.

According to trauma theory researcher Cathy Caruth, who develops the thought of Sigmund Freud, a person who has undergone a traumatic experience is constantly repeating it [4]. This involuntary re-experiencing of the event that cannot simply be left behind both retraumatizes and allows for a gradual rethinking of the experience.

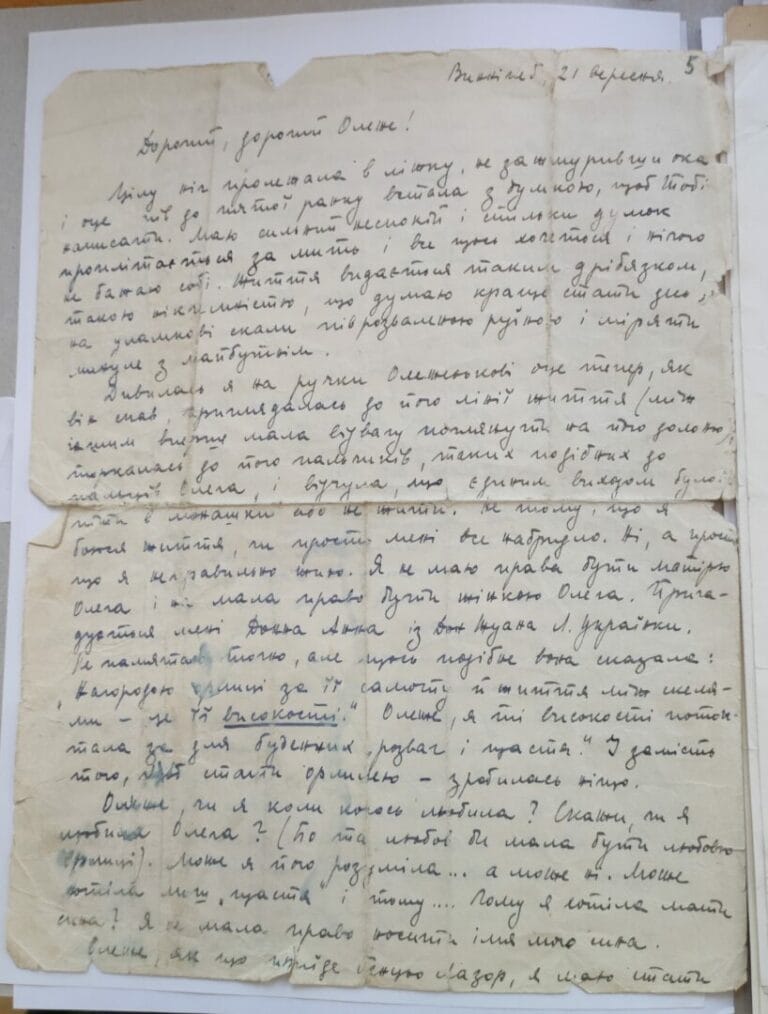

Some of Biletska’s letters are full of despair: “I am not capable of anything here. It seems to me that I have ceased to exist here. Nothing moves me, I don’t want anything, I don’t long for anything.” Her letters to Lashchenko become a kind of psychotherapy where she can express her feelings: “Life seems so trivial, so insignificant that I think it’s better to stand somewhere on a rock fragment as a run-down ruin, and measure the past with the future”; “…the only solution was to become a nun or not to live. Not because I am scared to live, or just fed up with everything. No, but simply because I don’t live the right way. I have no right to be Oleh’s mother and I had no right to be Oleh’s wife.”

Kateryna also recalls the day she learned the news of Olzhych’s death from Andrii Melnyk: “I didn’t cry then either. But I clenched my teeth so firmly that my jaws hurt,” and “I couldn’t realize the horror that he was gone.” Biletska doubts whether she truly understood her husband and reflects that she wanted her son more than anything else, wanted happiness.

In October 1950, she married journalist Yevhen Lazor and became the editor of the Ukrainian Women’s Organization of Canada’s magazine, Women’s World. For about thirty years, she worked in the acquisitions and binding departments, as well as the Slavic studies department at the University of Toronto. She tried her hand at science, directing, and fiction: she researched the Ukrainian press in the Czech Republic in 1848-1919, directed the children’s theater “Grandma’s Fairy Tale,” and wrote for children. The letter below provides insight into her situation, mentioning that she transcribed for Ukrainian studies courses and earned $15.

The second issue of the Women’s World magazine contains her article “The Role of Lesia Ukrainka’s Parents in Her Spiritual Growth,” along with the poem “And Yet My Thought Flies Back to You” (“I vse-taky do tebe dumka lyne”) by Lesia Ukrainka, which probably reflected Biletska’s own inner state. In this issue, under the pseudonym Grandma Kalyna, Biletska’s fairy tale The Princess Swan was published as well, a variation on the chronicle legend about the Lybid and the founding of Kyiv.

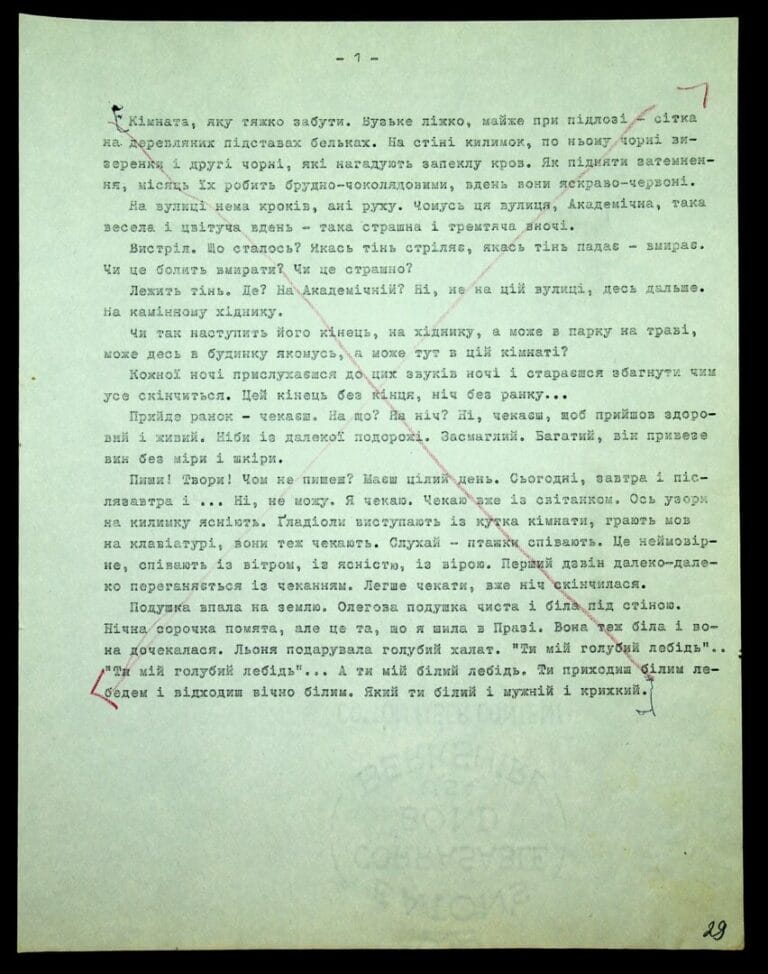

Gradually, Biletska becomes inspired by a new idea – a memoir project. She organized the archives of her father, Leonid Biletskyi, and donated his manuscripts and correspondence to the Ukrainian Free Academy of Sciences in the 1980s. And after observing the activities of the widow of assassinated President John F. Kennedy, as mentioned in a letter to Lashchenko, she decides to start writing up her own memories of Olzhych and her own youth. She discusses this idea with Lashchenko and writes that she dreamed of not working at all for a year so that she could devote herself entirely to writing her memoirs. However, this was not possible, so “I have to continue slogging through my ‘existentia’.” Kateryna edits, crosses out, and reprints on a typewriter. She rejects some memoirs that were never published and are kept as drafts at the Institute of Manuscript of the Vernadsky National Library of Ukraine. She corresponds with Olzhych’s acquaintances. In 1977, Biletska even wrote a letter to Ethel Lesser, Olzhych’s former fiancée. Lesser sent her letters and belongings she preserved, including dried rose petals and a doll in Ukrainian folk costume that Olzhych had given her.

Overcoming depression (Biletska uses this word in her correspondence with Lashchenko) and finding words to represent trauma was partly facilitated by the discovery of the role model, namely Jacqueline Kennedy, as well as the activation of collective memory – memories of World War II survivors were being published, and a public narrative about the role of Ukrainians in the struggle for independence began to emerge in the diaspora. Since residents of Soviet Ukraine were not able to broadcast their traumatic experiences openly, and contacts with Ukrainian emigration were occasional, the comprehension of individual and collective traumas was renewed only after 1991, and it reached a new level after 2014. As the researcher of traumatic experiences Marinella Rodi-Risberg points out, the transformation of individual suffering into collective trauma depends on ritual, political action, and various forms of narrative [5].

Trauma increases the existential threat that prompts the search for meaning, and the experience and comprehension of trauma becomes a process of identity construction [6]. It is cynical to talk about the creative potential of trauma, because a person’s self-determination is possible without it, but when this experience does happen, one has to live with it. The memory of trauma prompts attempts to construct meaning around the experience of extreme distress, and it allows one to regain a sense of control over one’s own life. Writing her memoirs was an attempt for Kateryna Biletska to make sense of her own tragedy.

References:

[1] Zubko, O. “Prague everyday life of Professor Vasyl Simovych (1923-1933)” [Празьке повсякдення професора Василя Сімовича (1923–1933)]. History Journal of Yuriy Fedkovych Chernivtsi National University. Chernivtsi: Chernivtsi University, 2022. № 1. 47.

[2] Kardash. “Ukrainian preschool education” [Українське дошкілля]. Neznanomu voiakovi. Kyiv, 1994, 132.

[3] Lazor, K. “Following Olzhych in thoughts” [Думками вслід за Ольжичем], The Ukrainian Historian. 1985. No. 1-4; Lazor, K. “Olzhych in my memories” [Ольжич, яким я його пам’ятаю], Oleh Olzhych. Tsytadelia dukha. Bratislava, 1991.

[4] Cathy Caruth, “Introduction: The Wound and the Voice”, Unclaimed Experience: Trauma, Narrative and History. JHU Press, 1996, 1-10.

[5] Marinella Rodi-Risberg, “Problems in Representing Trauma” Trauma and Literature. J. Robert Kurtz eds. Cembridge UP, 2018, 110-124.

[6] Gilard Hirshberger, “Collective Trauma and the Social Construction of Meaning” Frontiers in Psychology. Vol. 9, 10.08.2018, 1-14.

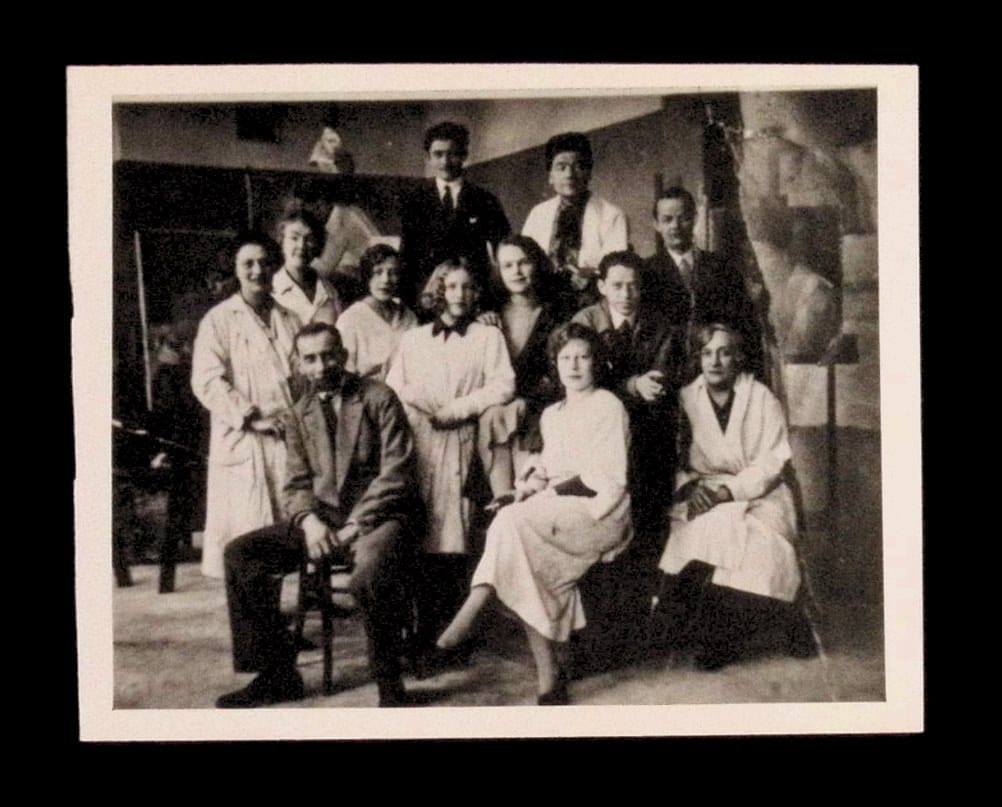

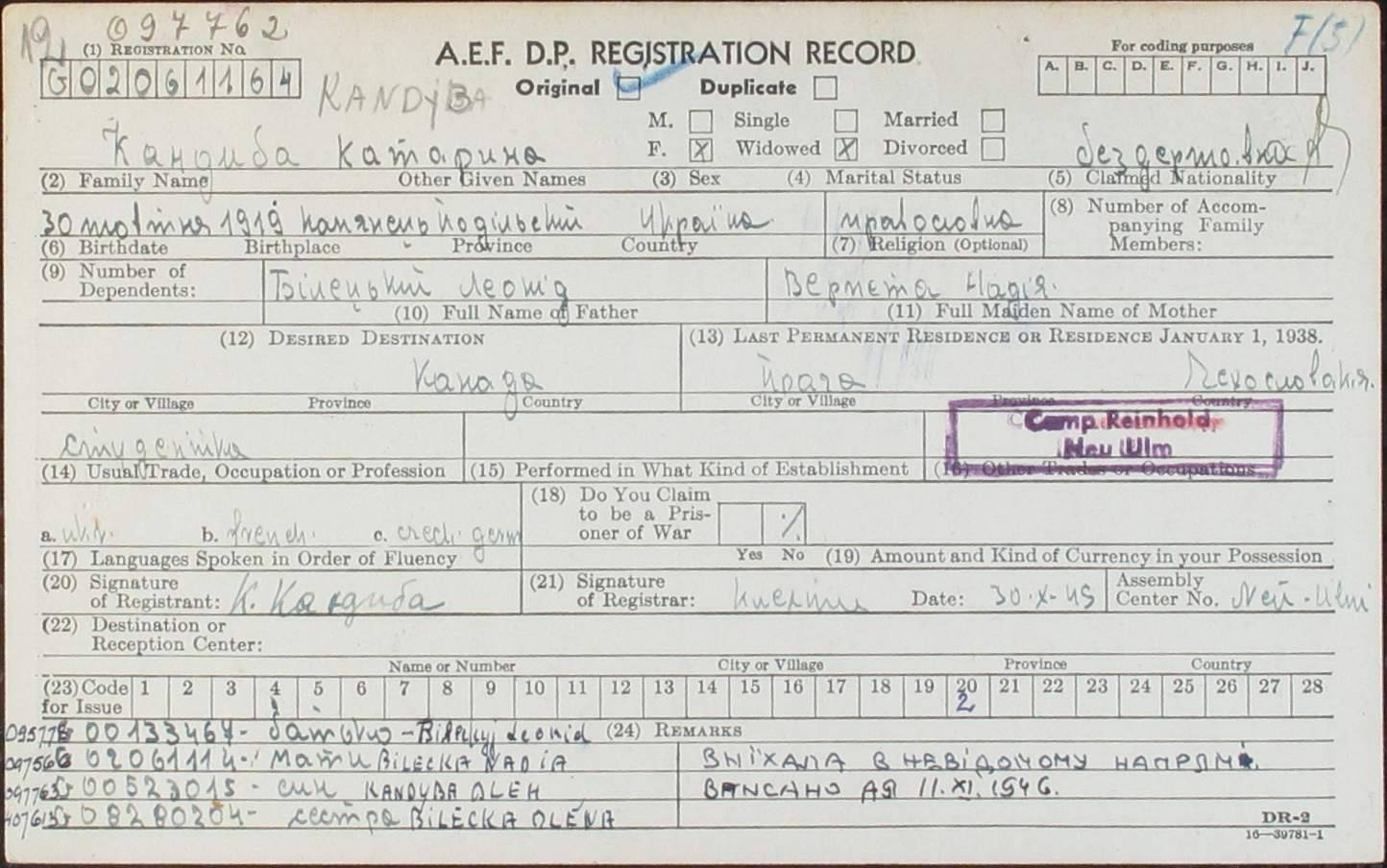

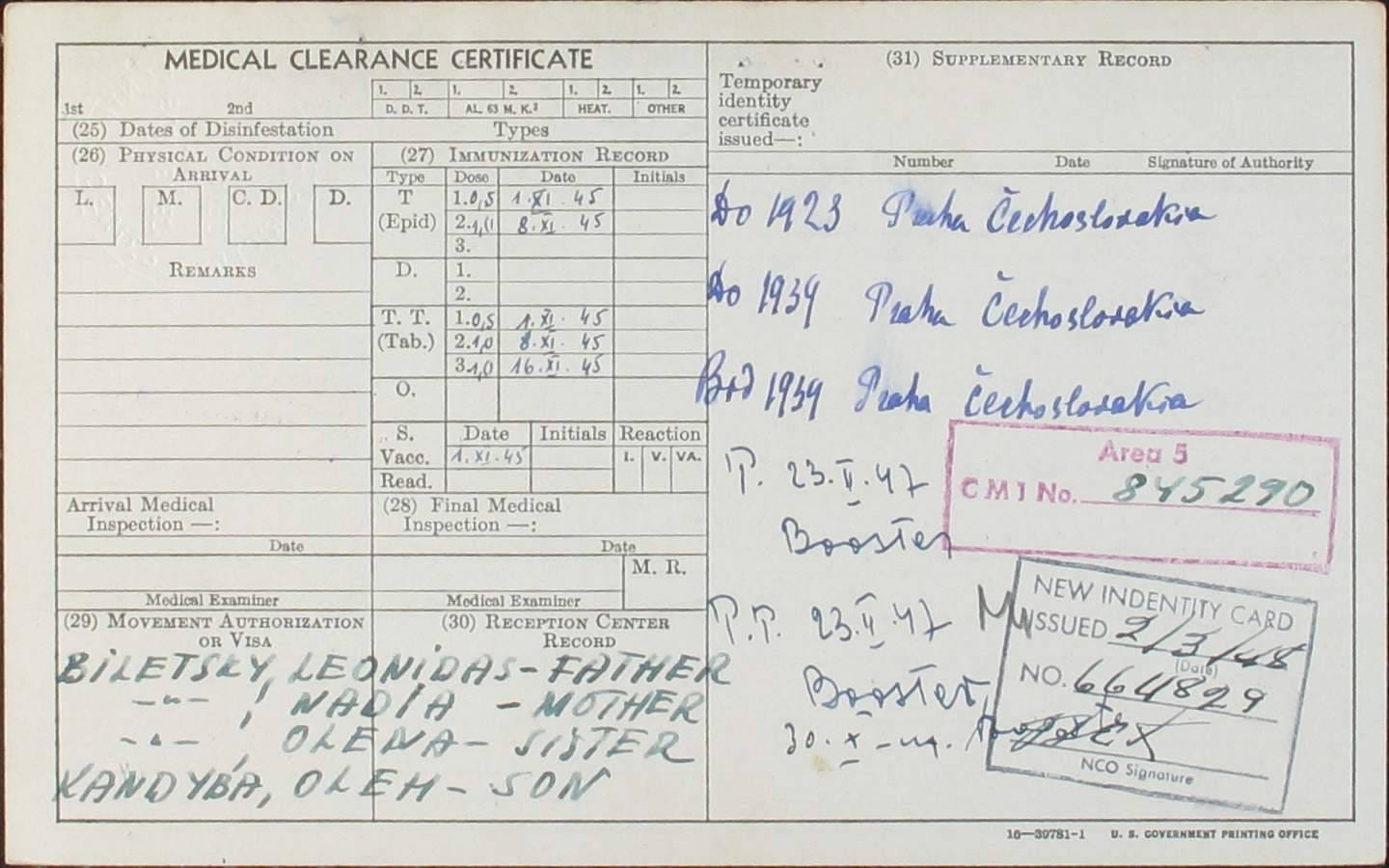

Photos courtesy of the author.

Translated into English by Yulia Kulish