The two-part feature film, directed by Eldar Riazanov, was first broadcast on January 1, 1976, at 18:00 on the First Program of the Central Television of the USSR. The premiere attracted an audience of approximately 100 million viewers, and due to overwhelming public demand, it was re-aired on February 7 of the same year. According to estimates by film historian Razzakov, by 1978, around 250 million people had watched the film [1]. Its immense popularity quickly cemented The Irony of Fate as an integral part of Soviet New Year’s traditions, alongside champagne, caviar, chimes, and the ritual of holiday television viewing.

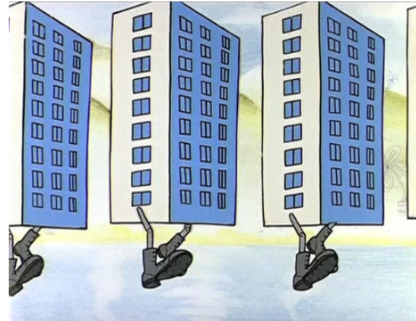

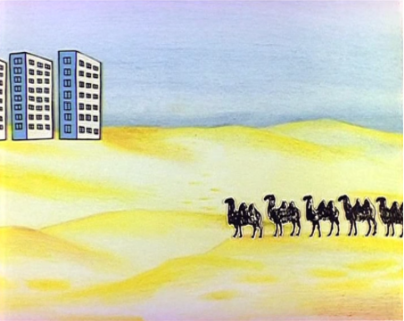

The film opens with a short satirical cartoon, created and animated by Vitaly Peskov, who lived in Moscow’s Cheryomushki district. This animated sequence critiques the uniformity of Soviet urban planning, presenting a conceptual contrast between “standardized” and “individual” designs, as well as the tension between “bureaucratic” and “creative” approaches. The story follows an architect who envisions an original, elaborate building adorned with columns, staircases, and balconies. However, as his design passes through various levels of bureaucratic approval, each revision strips away decorative elements until the once-distinctive structure is reduced to a standard Soviet “box.” Though only three minutes long, the cartoon serves as a crucial part of the film’s prologue, reinforcing themes later echoed in the opening monologue on Soviet architecture.

This monologue, delivered over visual plans of a typical Soviet city, sets the stage for the film’s central motif:

“In the old days, when someone arrived in a new city, they felt lost and out of place—unfamiliar streets, unfamiliar houses, an unfamiliar way of life. But today, things are different. Now, wherever a person goes, they feel at home. How foolish our ancestors were, agonizing over every architectural project! Today, every city has a typical ‘Rocket’ cinema where you can watch a typical feature film. <…> Street names are the same: almost every Soviet city has its own Cheryomushki, indistinguishable from the rest. What city doesn’t have a 1st Sadovaya, 2nd Zagorodnaya, or 3rd Fabrichnaya? A 1st Parkovaya, 2nd Industrialnaya, or 3rd Stroitelnaya? It’s beautiful, isn’t it? Identical stairwells painted in the same pleasant colors, standard apartments filled with uniform furniture, and faceless doors fitted with identical locks.”

Following this ironic monologue, visually accompanied by architectural plans of a typical Soviet city, the film presents its epigraph: “A completely atypical story that could only happen on New Year’s Eve.” This text, set against sweeping shots of a snowstorm and a multi-story residential building, underscores the film’s fairy-tale quality, aligning it with the tradition of Christmas (or, in Soviet culture, New Year’s) stories, where the extraordinary is always possible. While this epigraph signals the film’s whimsical nature, its true significance becomes clear only in relation to the opening monologue, which emphasizes the monotonous uniformity of Soviet urban life.

In 1969, Soviet playwrights Emil Braginskiy and Eldar Riazanov wrote the play Enjoy Your Bath! Or Once Upon a Time on New Year’s Eve, which quickly became a favorite in Soviet theaters. In the early 1970s, the decision was made to adapt it for television, leading to the premiere of the two-part TV movie during the New Year’s holidays of 1975–1976. Much like the 1959 Moscow operetta about the Cheryomushki neighborhood, a popular theatrical plot was reimagined in a new medium—this time, not through cinema but television. Unlike the 1963 film musical Cheryomushki, the adaptation took the form of a television movie enriched with numerous musical interludes, which became widely popular after its release in 1976.

The film’s lyrical songs, featuring poetry by Yevgenii Yevtushenko and Bella Akhmadulina and performed by Sergei Nikitin and Alla Pugacheva, became as beloved as the movie itself. They evoked a unique sense of nostalgia and a distinct form of socialist romance. The 1970s in the Soviet Union were an era of guitar-strumming bards performing on hiking trips, in parks, and at celebrations. It is no surprise, then, that the film’s “guitar songs” resonated deeply with audiences and became a cultural phenomenon.