Despite state control over media, home movies emerged and gradually developed in the USSR—particularly from the 1950s onward, when 8mm cameras became more affordable. These films typically documented family events, travel, and scenes from everyday life. Unlike in the West, however, they were far less likely to be made public. Amateur films could only be shown through officially sanctioned festivals, and ideally in cooperation with state-run amateur studios affiliated with production enterprises.

A network of so-called “people’s film studios” and film clubs across the Soviet Union provided opportunities for cinema enthusiasts to experiment with the medium. These clubs frequently organized local screenings and competitions. The state supported such initiatives insofar as they promoted Soviet values, creating a paradoxical space in which amateur filmmakers enjoyed a degree of creative freedom but remained confined within strict ideological boundaries—and could not always present their work to the broader public. Amateur photography, using accessible Soviet-made cameras like the Russian Zenit or the Ukrainian FED, was far more widespread than amateur filmmaking, which remained limited due to technical and logistical constraints. In the 1980s, some enthusiasts began to gain access to portable video cameras, yet VHS and home video culture only truly took root during Perestroika and the post-Soviet period.

Home movies and videos today serve as valuable historical testimonies, documenting the everyday practices, rituals, and social structures often ignored by mainstream media. They offer alternative perspectives on the past, complementing official archives and artistic works with personal, marginalized, and non-institutionalized narratives. The study of amateur media not only reveals the evolution of media technologies—from analog film to video to digital platforms—but also challenges the conventional boundaries between personal memory, domestic life, and public cultural history. Amateur cinema is distinguished by its specific visual aesthetics and narrative techniques, which deviate from the norms of commercial or state-produced film and lend it particular historical and cultural value.

The Urban Media Archive at the Center for Urban History in Lviv includes a series of film recordings by Lviv-based media amateur Albert Patai, a member of a film club at the Lviv branch of the Ukrainian Society for the Deaf. His family, like many others with hearing impairments, lived in specially designated or adapted housing complexes with access to Ukrainian Society for the Deaf infrastructure. In the Ukrainian SSR, such societies often operated cultural centers that hosted amateur groups, including film clubs. Patai’s recordings date from the early 1970s—one reel is specifically labeled 1974, though it likely contains scenes shot at different times. This period coincides with the large-scale resettlement of Soviet citizens into newly constructed residential districts in socialist cities, which played a crucial role in the modernization efforts of that era.

At the beginning of the film, the filmmaker seeks to capture the rhythm of daily life in the communal yard: we see plants, a dog, and children playing. Amateurs often recorded such everyday scenes on a single reel, which means a single tape could document the passage of time—even seasonal transitions. On this reel, a hand-written note appears on screen, filmed directly: “First snow, October 31 – November 2, 1974.” The scene shows an autumn that already looks like winter. The camera pans over a cityscape of typical Lviv apartment blocks, their rooftops crowded with television antennas. Most likely, the author wanted to record the first snowfall—a noteworthy event in Lviv—but alongside it, he captures something more intimate: a quiet interaction between a grandmother and her granddaughter in the apartment kitchen. The camera alternates between the snowy yard outside and the warm, domestic interior, where the grandmother is feeding the girl. At one point, we see a close-up of a woman’s face as she speaks, but her words remain inaudible. Then we return to the yard, where snow falls more heavily, before shifting again to the grandmother bustling in the kitchen. The sequencing suggests a deliberate attempt to construct a visual narrative, using cinematic techniques such as shot and reverse shot—reminiscent of professional film editing.

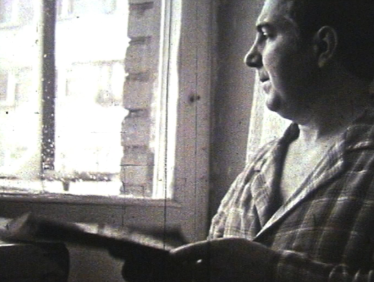

Next, we see the granddaughter playing with a caged bird, followed by a cut to the same girl posing outside in the snow, bearing witness to the unexpected early snowfall of 1974. Then, the camera is set on a tripod. In a meta-cinematic moment, the filmmaker steps into the frame himself. This is Albert Patai. He looks out the window and flips open a copy of Soviet Photo magazine, subtly identifying himself as a Soviet media amateur. The camera shifts again to the balcony, where we see a small birdhouse—typical of those Soviet city dwellers placed to feed birds in winter. Such feeders were common, often built by parents and children as part of school assignments promoting care for nature. The camera lingers on the birdhouse, suggesting it holds symbolic meaning for the filmmaker—perhaps representing both the apartment as a shelter and the home as a shared space with non-human life.

Then, in a striking juxtaposition of media, the filmmaker attempts to record scenes from popular cartoons on the television screen—Nu, Pogodi! and Gena the Crocodile. Abruptly, the frame shifts again to show the grandmother knitting and speaking, while the granddaughter plays nearby. The family appears immersed in ordinary domestic rituals: watching TV, knitting, playing, simply being together. The filmmaker then directs the camera toward the window, filming the world outside—neighbors walking, children playing in the snow. The camera returns to the television, where we see footage of Soviet cosmonauts and a rocket launch. The TV emerges as the central “bard” of Soviet life: it structured time, organized space, and served as a window into the wider world.

In addition to the official media (ekklesia)—the imagined narratives and myths presented through theatrical performances, films, and other sanctioned representations consumed by Soviet citizens in the agora (for instance, in cinemas as part of the public sphere, or via television as a window onto it)—there also existed a private sphere (oikos). But how can we uncover what everyday life was like for ordinary people? One valuable source for accessing this lived reality is amateur film recordings, which captured fragments of daily life in cheryomushky and khrushchovkas.

The Soviet Union maintained a unique ideological system that simultaneously restricted and encouraged amateur media. The state promoted amateur filmmaking through official clubs—such as those affiliated with the All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions—and through branches of the Union of Cinematographers, which began operating a dedicated amateur section in the late 1950s. These clubs enabled non-professionals to create their own films, typically using 16mm or 8mm cameras, albeit within strict ideological boundaries. While amateur filmmakers enjoyed relatively more creative freedom than their professional counterparts, they were still expected to adhere to the tenets of Soviet ideology. As a result, these films often focused on themes such as socialist industry, everyday life, workers’ achievements, and local events, depicted in ways that reinforced the values of the socialist system. Experimental or overtly critical content was not permitted, though some filmmakers managed to express subtle dissent through irony or allegory.