The Soviet government aimed to profoundly transform the styles and structures of people’s everyday lives, encompassing housing, leisure, and work. Particularly ambitious projects were conceived and executed during the 1920s and 1930s. Workers were at the forefront of Soviet social policy, with the Bolshevik Communist Party depicted in Soviet discourse as the avant-garde of the proletariat, primarily serving the interests of the working class. One of the government’s first initiatives was to relocate workers from suburban areas to apartments previously occupied by the “bourgeoisie” in the central districts of cities. Party functionaries, invoking the concept of social justice, endeavored to redistribute resources in favor of those who had been stripped of privileges under the old regime. Through this, the Soviet government sought to provide workers with housing, thereby granting them tangible advantages in society. It can be asserted that this project either failed outright or yielded considerably fewer results than anticipated.

Several factors contributed to this situation, including workers’ apprehension about the stability of the Soviet regime, reluctance to relinquish the social connections established during their tenure in the outskirts of the city alongside their former neighbors, concerns about the challenges associated with heating larger apartments in the city center—requiring more resources compared to smaller apartments on the outskirts—and their aversion to spending additional time commuting from the city center to their workplaces, among others.

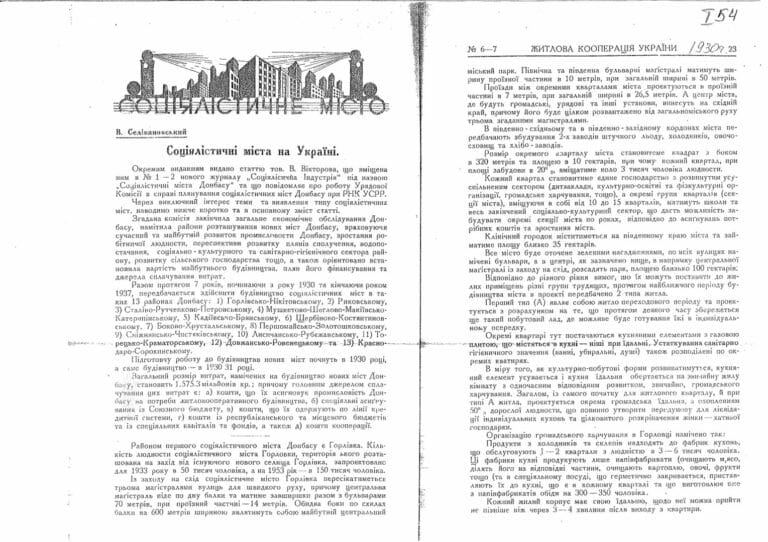

One of the most radical initiatives aimed at cultivating a new way of life and molding the new Soviet citizen was the establishment of socialist towns. These urban centers were strategically constructed adjacent to key industrial facilities, emblematic of the Soviet Union’s drive towards forced industrialization in the Ukrainian SSR, such as DniproHES and the Kharkiv Tractor Plant. The architectural design of these socialist towns served as a visual manifesto of the era. In the early 1930s, several socialist towns were designed in the Ukrainian SSR (“Velyke Zaporizhzhia,” [Big Zaporizhzhia] “Novyi Kharkiv,” [New Kharkiv] etc). In 1929-1930, there was an ongoing debate between “urbanists” and “disurbanists,” in the pages of specialized publications on socialist settlement, about what their spaces should look like. All participants agreed that socialist towns should contribute to the socialization of workers’ everyday life. For instance, in the design for Kharkiv Tractor Plant town, “New Kharkiv,” kitchens were intentionally omitted. The rationale behind this decision was to foster the development of a communal catering system and “liberate women from the drudgery of kitchen work.” Nonetheless, due to the inadequate development of the canteen network, individuals continued to cook and dine at home. It’s worth noting that many of the workers hailed from rural backgrounds, thus gradually acclimating to urban life while adapting the layout of their new apartments to suit their accustomed peasant lifestyle needs. The downside of industrialization was the urban sprawl. Residents resorted to unconventional measures such as keeping poultry on their balconies and housing pigs in their bathrooms. Despite its ideological importance, a consistent model of a socialist town failed to materialize. Instead, we can identify a particular framework—a set of basic principles—guiding the creation of new urban layouts: deliberate urban planning, consistent infrastructure development, proximity of residences to industrial enterprises, a homogeneous social demographic comprised mainly of workers, extensive socialization of daily life, and abundant green spaces. The construction of socialist towns served as a manifestation of novel social ideologies translated into architectural form. Despite its shortcomings and subpar quality, the “New Kharkiv” socialist town stood as one of the pioneering instances of standardized housing construction in the USSR. In the subsequent decades, particularly during the Khrushchev era, the housing plant that formed the foundation of this socialist town served as a blueprint for the expansion of Soviet urban areas characterized by microzoning.

Simultaneously with the forced industrialization of the Ukrainian SSR, there occurred a compulsory collectivization of agriculture. Between 1932 and 1933, the republic endured the Holodomor, orchestrated by the Soviet authorities, claiming the lives of an estimated 4 million individuals. Internal passports were implemented to restrict the movement of peasants, though they were often denied issuance. Furthermore, stringent sanitary cordons were established around major cities. Peasants attempting to travel by train were intercepted, while police patrols on roads apprehended those journeying towards urban areas. Nonetheless, numerous individuals succeeded in reaching regional centers despite these measures. Lines formed outside grocery stores, with weary individuals clad in tattered clothing, and corpses strewn along the roads; these sights became common and integral aspects of urban life. This grim reality is vividly depicted in the photographs of Alexander Wienerberger, an Austrian engineer stationed in Kharkiv. Amidst this bleak landscape, workers hurried to their workplaces, navigating past the tragic scenes of peasant corpses. Among the notable foreigners striving to shed light on the Holodomor was Welsh journalist Gareth Jones. There are also instances of other published accounts authored by individuals who bore witness to the Holodomor in Ukrainian cities.

Promoting the transformation of tradition and the introduction of novel forms of leisure stood among the key objectives of the Soviet government’s social policy. The endeavors of the Bolsheviks in this realm could be described as striving to indirectly standardize everyday life. Workers’ clubs served as instrumental platforms for introducing Soviet holidays and rituals marking life events (“octobering,” red weddings, etc.). Within these venues, the government presented itself as a staging orchestrator. The clubs spearheaded ideological campaigns aimed at social mobilization (combating hooliganism and traditional lifestyles, and advocating for party “purity” or solidarity with republican forces during the Spanish Civil War, etc). In the late 1920s and early 1930s, concurrent with political and socio-economic shifts in the country, new ideological objectives were appended to the clubs’ agenda, transforming them into centers for the re-education of workers. Club leaders were tasked with engaging in party purges, enhancing workers’ technical proficiency, organizing social competitions, meeting quotas, and more.

Furthermore, in Soviet discourse, workers’ clubs were portrayed as the sole venues designated for recreational activities for the working populace. However, the clubs’ agenda, heavily laden with ideological campaigns, often deterred workers from attending. Club leaders faced the ongoing challenge of striking a balance between ideological agitation and providing enjoyable entertainment. The clubs found themselves in a constant battle to attract visitors, facing opposition from pubs and churches. Prior to religious holidays, club administrators arranged dances or games with prizes. Conversely, on communist holidays such as May Day or Paris Commune Day, to engage workers in political discussions, they offered to conclude the event with a film screening. Workers, driven by practicality, seized this chance to exhibit loyalty to the authorities while enjoying themselves after the formal proceedings. Lecturers commonly lamented that their speeches were frequently disrupted by audience shouts demanding, “Enough! Give us a movie!”

It is noteworthy that the administrators of workers’ clubs often regarded their positions as a means of advancement and career progression. A common scenario involved officials treating propaganda efforts perfunctorily, with leisure activities at the club limited to games like dominoes. However, workers exhibited a strong inclination towards reading, particularly favoring adventure, light, and entertaining literature. The surge in the publication of such books in Ukrainian during the late 1920s, spurred by Ukrainization, was a response to this reader interest. Despite the Soviet government’s efforts to politicize workers’ leisure time, numerous gaps at the grassroots level persisted beyond ideological control. Authorities labeled apolitical behavior as an anomaly, yet for most Soviet citizens, it was the norm and a coping strategy in everyday life.

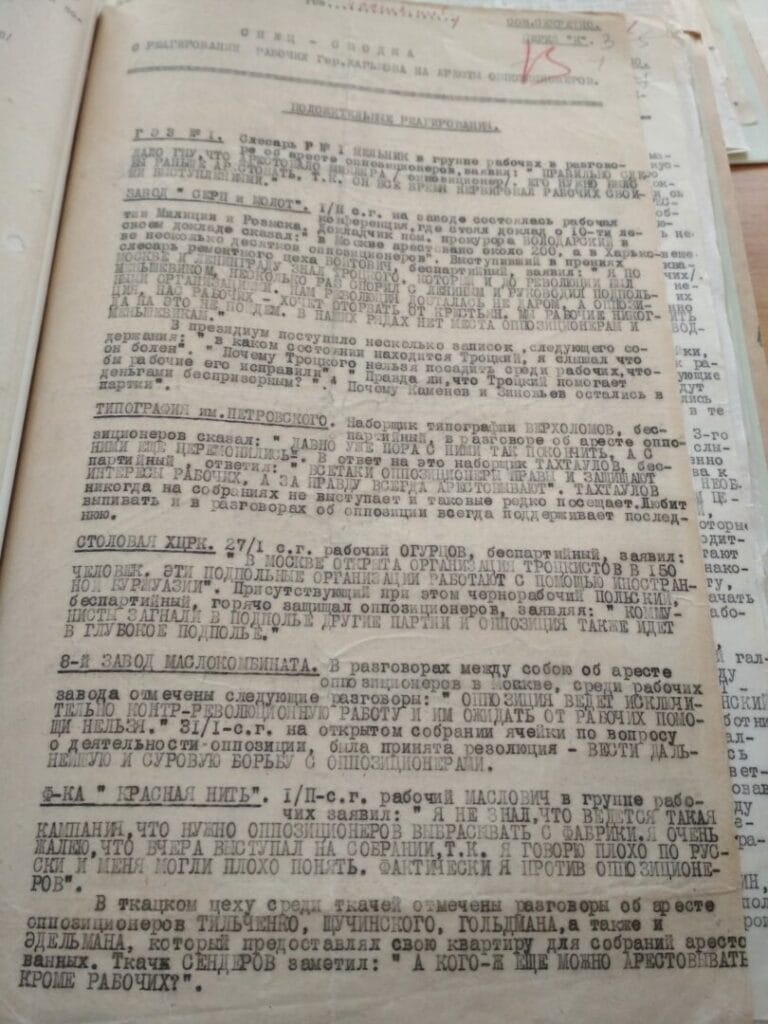

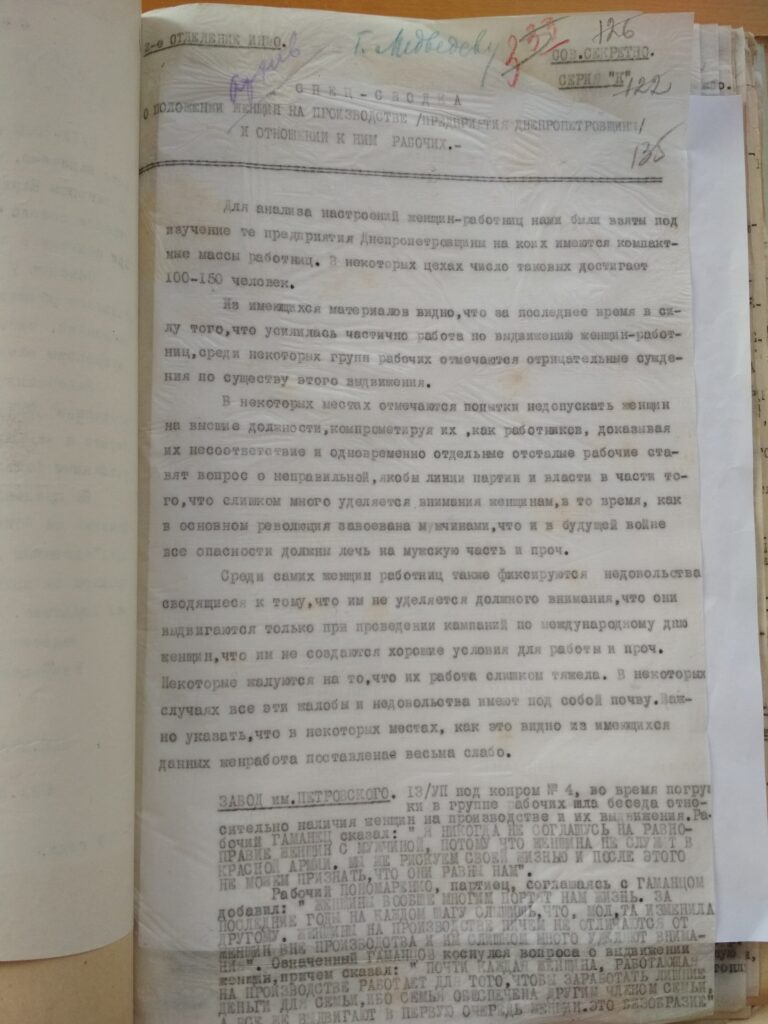

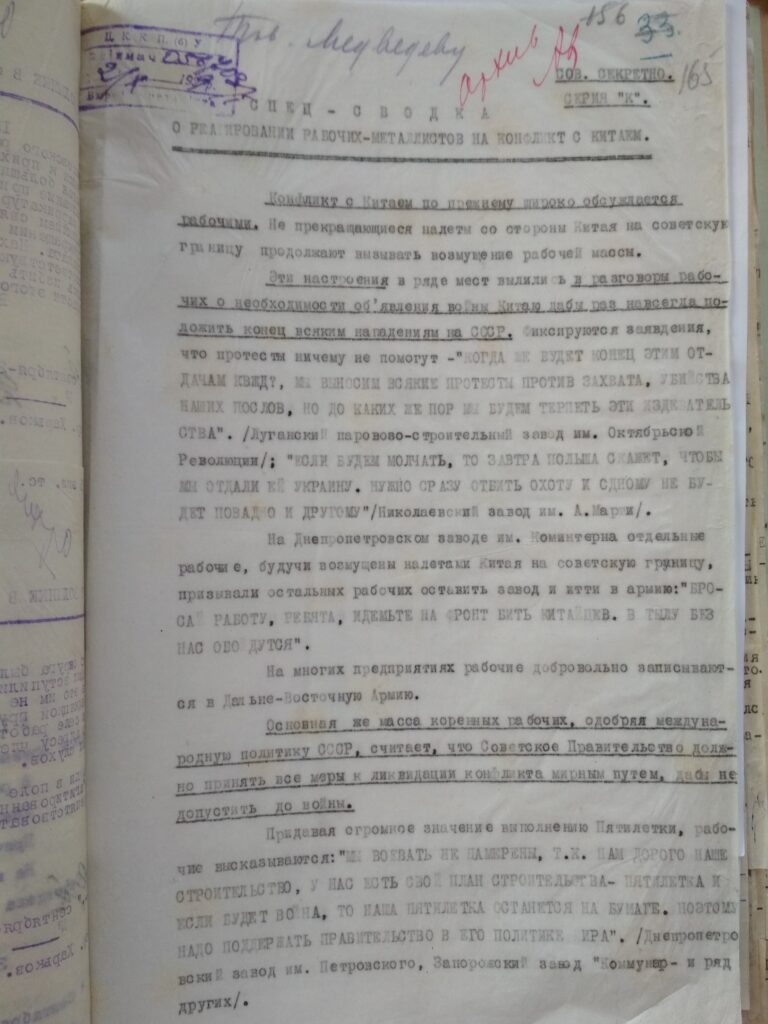

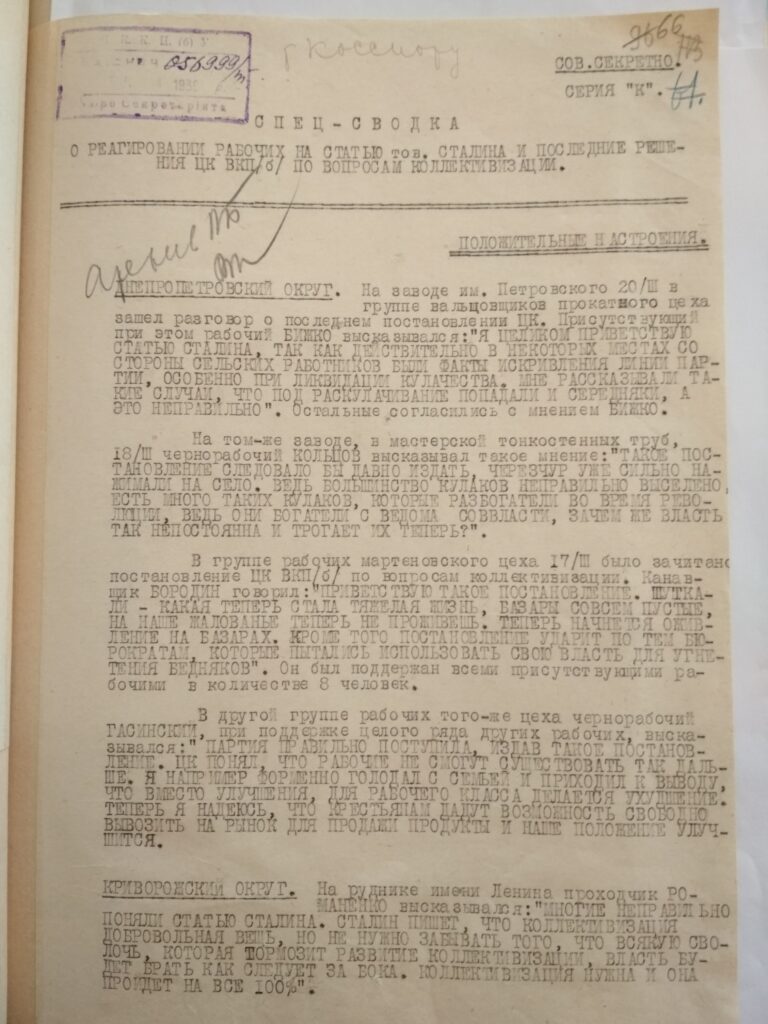

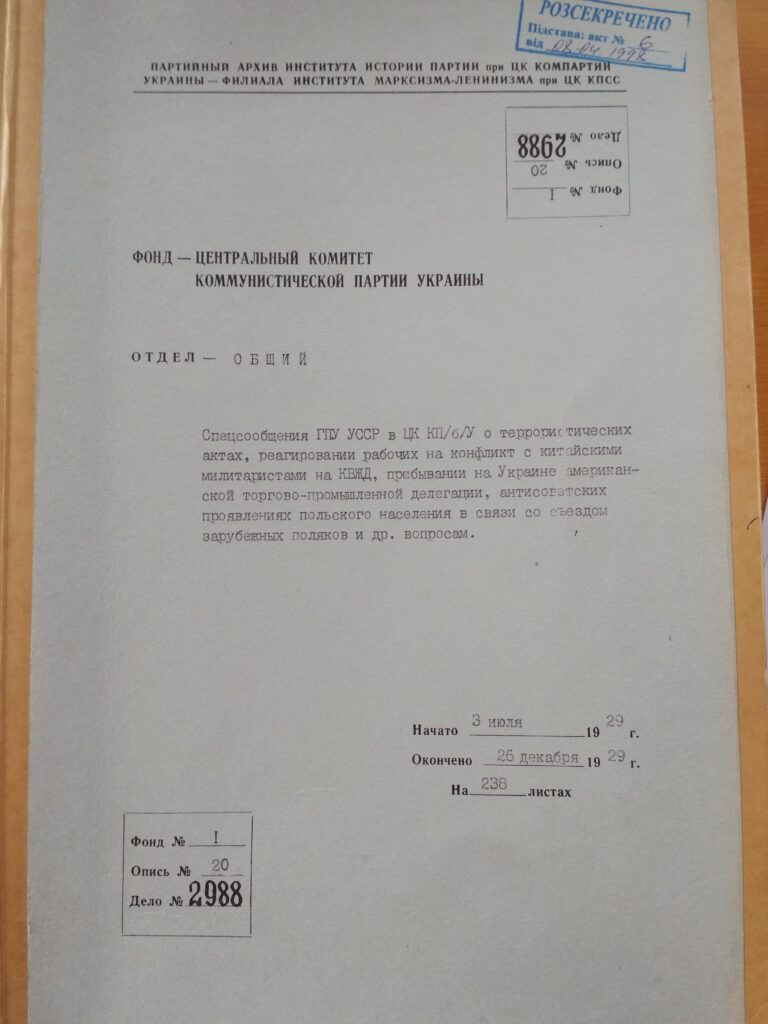

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, the Ukrainian SSR underwent a transition towards totalitarianism. This period was marked by the arrest of opposition figures, the fabrication of cases, and show trials (such as the Shakhty trial and the trial of the Union for the Liberation of Ukraine), widespread repression, the implementation of collective farming, and the brutal suppression of the peasantry. These events were not merely a facade of political or economic life but deeply intertwined with the daily experiences of workers. In various capacities, workers found themselves entangled as actors within these processes. Public silence or discussions about the prevailing situation in the country constituted a significant aspect of socio-cultural reality. The authorities diligently and systematically gathered information about the sentiments of the workers, recognizing the importance of public opinion even within a totalitarian regime. Following Stalin’s significant and pivotal political maneuvers (such as the deportation of Leon Trotsky, engagement in the war with China, and the campaign against the “kulaks”), internal affairs authorities meticulously monitored the mood among the workforce. This enabled the party leadership to tailor the narrative of authority, steering and strategizing its future actions. Workers’ conversations during breaks, preceding and following trade union and other gatherings, held considerable interest for the authorities. The opinions and evaluations documented by the special services provided the authorities with insight, allowing them to remain attuned to public sentiment and accurately evaluate the situation. In this manner, a form of interaction with the authorities unfolded, with the voices of workers being systematically documented in special reports and analyzed by party officials. The spectrum of sentiments and responses from the populace towards the government’s actions extended far beyond a simplistic support-opposition dichotomy. Workers could publicly express support for the regime while privately criticizing it, partake in Soviet celebrations while simultaneously engaging in everyday forms of resistance, leverage propaganda activities to secure specific material advantages, and so forth. Furthermore, everyday resistance did not necessarily signify outright opposition to the regime. The authorities, while gathering information on the moods, actions, or remarks of workers, frequently categorized these as forms of protest or dissent diverging from the norm of behavior. However, for the workers themselves, such actions might not have been deliberate acts of opposition. James Scott, in his studies on Malaysian peasants, illustrated the myriad forms of everyday resistance. It is crucial to underscore that these conclusions hold significant relevance within the Soviet context. Scott observed that such resistance typically fails to bring about substantial changes, remains non-systemic and individualistic, and ultimately facilitates individual adaptation to the regime. Reports on the workers’ mood during 1929-1930 reveal frequent instances of criticism or rather ironic commentary regarding both domestic and foreign policies of the Soviet government. However, their actions remained within the bounds of “permissible dissent.” These boundaries were primarily delineated in the late 1920s and early 1930s, gained more prominence during the Great Terror, and subsequently became pivotal for Soviet society in the ensuing decades.

Literature

[1] Borysenko, М. V. (2009). Housing and Life of the Urban Population of Ukraine in the 20-30s of the Twentieth Century [Житло та побут міського населення України у 20-30-ті рр. ХХ ст.]. Kyiv: VD «Stylos», 183-210.

[2] Bauhaus – Zaporizhzhia. Zaporizhzhia modernism and the Bauhaus school: Universality of phenomena. Problems of preserving the modernist heritage [Баугауз — Запоріжжя. Запорізький модернізм і школа Баугауз: Універсальність явищ. Проблеми збереження модерністської спадщини]. (2018). Kharkiv: TOV «Disa Plius».

[3] Kuzina, К. Architectural paradise or prison for citizens? Designs of Socialist Cities in Soviet Ukraine (1929-1933) [Архітектурний рай чи тюрма для містян? Проекти соціалістичних міст радянської України (1929-1933 рр.)]. Ukraiina Moderna. https://uamoderna.com/md/arxitekturna-utopiya-chi-tyurma-dlya-mistyan-proekti-soczialistichnix-mist-radyanskoi-ukraini-1929-1933-rr/

[4] Christina, E. Crawford. (2022). Spatial Revolution Architecture and Planning in the Early Soviet Union. London: Cornell University Press, 221.

[5] Kulchytskyi, S., Yefymenko, G. (2003). Demographic Consequences of the Holodomor of 1933 in Ukraine. All-Union Census of 1937 in Ukraine: documents and materials [Демографічні наслідки Голодомору 1933 р. в Україні. Всесоюзний перепис 1937 р. в Україні: документи та матеріали]. Kyiv: Institute of History of Ukraine of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine.

[6] Ewald, Ammende’s. Muss Russland Hungern? Wien, 1935. https://www.garethjones.org/soviet_articles/thomas_walker/muss_russland_hungern.htm

[7] Fred, E. Beal. (1937). Proletarian journey: New England, Gastonia, Moscow. New York: Hillman-Curl.

[8] A naming ceremony which occurred during the early era of the Soviet Union.

[9] Rolf, M. (2013). Soviet Mass Festivals 1917–1991. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

[10] Liubavskyi, R. (2016). Daily life of Kharkiv workers in the 1920s and early 1930s [Повсякденне життя робітників Харкова в 1920-ті – на початку 1930-х років]. Kharkiv: Rarytety Ukraiiny, 138-168.

[11] Palko, О. (2019). Reading in Ukrainian: the working class and mass literature in early Soviet Ukraine. Social History 44: 343-368.

[12] Shlikhta, N. (2015). History of Soviet society: A course of lectures. 2nd ed. [Історія радянського суспільства: Курс лекцій. 2-ге вид., переробл. і доп.]. Kharkiv: Akta, 145-161.

Cover photo: A group of workers in the shop of the Elektrosyla No. 1 plant. Early 1920s Kharkiv. From the collections of the M. F. Sumtsov Kharkiv Historical Museum (photo provided by the author)