Metaphorically, the system of interaction between the government and the people in the USSR can be represented through Greek concepts such as ekklesia (ἐκκλησία), oikos (οἶκος), and agora (ἀγορά). The ekklesia symbolizes the sphere of political life, where the government engages with the people through decrees, mass media, and regulatory acts. It was within this domain that the professional community of architects and builders was assigned the task of addressing the housing problem in the Soviet Union. Those who lived in this new type of housing inhabited the space of the oikos—the private sphere where everyday life unfolded. But how can we “spy” on what happens within this sphere? Typically, the best sources are amateur media (photography, film, and video) that people used to document and archive their own lives. Beyond the sphere of power and the private realm, there was also the public sphere, known to the Greeks as the agora—a space of social and commercial interaction. For instance, a Soviet citizen would “encounter” the myth of individual housing at the movie theater (agora), whether by watching a comedy about life in Soviet apartments or newsreels touting solutions to the housing problem in the USSR.

In these distinct spheres—ekklesia, oikos, and agora—different media played crucial roles, linking specific imaginaries to politics and transforming realities into myths. Authorities issued decrees; professionals such as architects and builders published magazines; directors created films; television broadcast the news; and ordinary citizens took pictures of their daily lives. Media did not function in isolation but operated within their own established rules, genres, and forms. An example of how certain ideological constructs were transformed through the influence of Soviet media culture will be examined in this module. We will briefly trace the mediatization of the “housing issue,” exploring the idea of mass housing and how this phenomenon was perceived and represented in Soviet media culture [6].

Mikhail Bulgakov (1891–1940), a native of Kyiv, a man of imperial outlook and a critic of Ukrainian autonomy who later became a Soviet writer, frequently addressed the housing problem in the USSR in his works. He dedicated an entire story to the subject of communal apartments and returned to the theme in many of his literary texts. For example, his novella The Heart of a Dog (1925) is structured around the housing problem, with frequent references to communal apartments and the miserable, cramped rooms in which the characters are forced to live [7]. In his famous novel The Master and Margarita, Bulgakov includes a scene in which, following the death of one character (Berlioz), as many as 32 people suddenly emerge with applications for the newly vacated living space. Their appeals to the authorities range from pleas and threats to gag orders, denunciations, complaints about unbearable overcrowding and the impossibility of sharing an apartment with criminals, promises of suicide, and even confessions of secret pregnancies. Bulgakov famously places into the mouth of Voland—Satan’s embodiment in the novel—the assertion that Soviet people are like any others, but they have been profoundly corrupted by the “housing issue.”

Indeed, in the pursuit of a house or apartment, a Soviet citizen might be willing to do almost anything: from conquering Siberia to committing serious crimes. The Soviet government, which held a monopoly on resolving the housing crisis, skillfully exploited the promise of “free apartments” and the broader housing question to promote and implement various policies. Even during Stalin’s lifetime, the housing issue had already become central to the project of Soviet socialism. The first experimental frame-panel social housing buildings appeared in the Soviet capital in 1948, based on designs developed by Gosstroyproekt, the USSR Academy of Architecture, and Mosgorproekt, Moscow Academy of Architecture. These early buildings were still quite different from the standard Soviet housing that later became familiar: they featured decorative elements and had a higher number of storeys.

Characteristic, minimalist, and economical housing began to appear in the second half of the 1950s. The architect behind these typical residential projects was civil engineer Vitalii Lagutenko, often referred to as the “father of the Soviet Khrushchevka.”[8] Initially, these economical buildings were constructed with a steel frame and reached four stories in height. However, due to the high metal consumption—over 16 kg per cubic meter of building volume—architects soon transitioned to using prefabricated reinforced concrete frames, which reduced costs by a factor of four. This experiment in building affordable housing was deemed successful, and from 1950 onward, frameless panel houses began to be constructed in addition to frame-panel houses with connected joints. These new forms of housing appeared in cities such as Moscow, Leningrad, Kyiv, Magnitogorsk, and others [9]. The emergence of cheap housing, now being provided on a massive scale by the builders of socialism, was met with great enthusiasm by Soviet citizens, as it fulfilled one of the core promises of state communism.

It is no coincidence that from the mid-1950s onward, we can trace the mediatization of the housing construction issue: the entire system of Soviet media culture began to generate its own media products on this theme. These included official government texts such as the Resolution of the Council of Ministers of the USSR dated May 9, 1950, No. 1911, On Reducing the Cost of Construction, which launched the design of the first series of highly mechanized precast concrete plants. Another key document was the Resolution of the Central Committee of the CPSU and the Council of Ministers of the USSR from August 19, 1954, On the Development of the Production of Precast Concrete Structures and Parts for Construction, which marked the beginning of a large-scale shift toward new, progressive construction methods at that time [10]. The following year, in 1955, the government issued another significant decree, signed by Nikita Khrushchev, On the Elimination of Excesses in Design and Construction. This directive aimed to cut construction costs and curb the dominance of Stalinist classicism, which until then had served as the virtually official architectural style of the USSR.

The personal influence of Nikita Khrushchev, First Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee, on the development of housing construction in the USSR after Stalin is widely acknowledged. It is no surprise, then, that the cheap and compact apartment buildings became popularly known as khrushchevkas [11]. Although the authorities had already begun communicating innovations in housing construction in the early 1950s, progress in the sector remained relatively sluggish. That changed on July 31, 1957, when the CPSU Central Committee and the USSR Council of Ministers adopted a new resolution, On the Development of Housing Construction in the USSR, which marked the start of a new phase in Soviet housing policy. Soon after, the fields surrounding the village of Cheryomushki near Moscow became the site of an experimental construction project where five-story residential buildings were rapidly erected using prefabricated structures. While the Cheryomushki experiment drew on the technical developments of the preceding era, it was in 1957 that the principle of block development with medium-rise buildings spread across the entire country. The name “Cheryomushki” quickly became synonymous with the practice of mass housing construction aimed at relocating workers from overcrowded communal apartments and accommodating the waves of new factory workers arriving from rural areas.

Indeed, the early 1960s marked the beginning of an unprecedented era in housing development that transformed the urban landscape of cities and towns throughout the vast socialist empire. In Soviet Ukraine, the first khrushchevka appeared in Kyiv’s Pershotravnevyi residential area, where construction began in 1957. The scale of this shift is reflected in the statistics: while the total area of residential buildings commissioned in the USSR between 1951 and 1955 was 42,122 thousand square meters, this figure doubled to 87,429 thousand square meters between 1956 and 1960, and reached 94,994 thousand square meters between 1961 and 1965. By the end of the 1960s, nearly 60 million Soviet citizens had received new housing. Although the housing crisis in the USSR was never fully resolved, the sweeping changes of the 1960s brought significant improvements to the quality of life for millions.

The very year after construction began on the Cheryomushki housing estate in Moscow, in 1957, Soviet culture began to respond to the sweeping changes taking place in the country. Just ahead of the New Year holidays, on December 24, 1958, Moscow hosted the premiere of the operetta Moscow, Cheryomushki, with music specially commissioned from the renowned Soviet composer Dmitry Shostakovich and based on a libretto by Vladimir Mass and Mikhail Chervinskyi [12]. The musical performance quickly gained popularity, but it could not by itself convey the “good news” of housing reform to the wider population. That task increasingly fell to television, which was becoming the main tool for publicizing the Soviet government’s achievements in addressing the “housing issue.” It is no coincidence that in the early 1960s, television stories about the cheryomushki neighborhoods began to appear throughout the USSR. One such example was the 1960 report by the Lviv Television Studio, titled Lviv Cheryomushky, which showcased the construction of new social housing neighborhoods in the city [13].

Founded in 1955, the Lviv Television Studio had been actively producing local news since 1957. The 1960 broadcast described the first wave of low-rise residential construction in Lviv, designed by Heinrich Schwieckyj-Vińcki and Lyudmyla Nivina, beginning in 1957. According to local researchers, it was not until 1962–1963 that the mass construction of high-rise residential buildings began (under the direction of architects Oleh Radomskyi and Liubomyr Korolyshyn), an effort that significantly transformed the landscape of the postwar city [14]. Thus, the solution of the “housing issue” in Lviv and its portrayal in television media remained closely intertwined.

In the early 1960s, the success of the operetta was set to be repeated—this time on the silver screen. The Lenfilm studio adapted the popular Moscow, Cheryomushki operetta into a musical film, which premiered across Soviet cinemas in the spring of 1963 [15]. Directed by Herbert Rappaport, the film unfolds in a newly built residential district of the Soviet capital. Its plot follows the lives and romantic entanglements of several young characters, each dreaming of a better life and a home of their own. Along the way, they encounter familiar bureaucratic hurdles, the schemes of corrupt officials, and the everyday challenges typical of Soviet reality. Yet, the film’s dominant notes are optimism, faith in a brighter future, and the lighthearted struggle of ordinary people against bureaucracy. Brimming with cheerful songs, energetic dances, and a satirical take on the housing distribution system, the musical reaches its emotional peak in a festive housewarming scene: in the apartment awarded to a pair of newlyweds, the new residents of the building gather to offer their congratulations. Their shared joy bursts forth in a lively polka, danced with exuberance by all. This film stands as a colorful example of Soviet entertainment cinema, blending propaganda with an upbeat vision of social progress and the promise of happiness in the new residential neighborhoods.

Joyful milestones in the lives of Soviet citizens—such as housewarming celebrations in newly built Khrushchevka apartments—were not only depicted in films but also captured by the people themselves with portable cameras, which began to be manufactured in the USSR in the late 1950s. By the 1960s, a culture of private home filmmaking had taken root, allowing us today to glimpse how residents lived in the new cheryomushki and khrushchevka neighborhoods. Indeed, the “joyful” narrative—the government placed great emphasis on public displays of happiness—around the resolution of the housing problem reached its peak in Soviet media culture during the 1960s. This theme united official speeches by party leaders, articles in professional journals, theater productions, films, and television broadcasts. Over time, however, the initial enthusiasm began to fade. By the 1970s, members of the postwar generation increasingly questioned the meaning of life in the uniform and repetitive districts that now defined Soviet cities. What was once promoted as a source of joy and progress gradually settled into the realm of the mundane and the banal.

In 1969, Russian playwrights Emil Braginsky and Eldar Ryazanov wrote the play Enjoy Your Bath, or Once Upon a New Year’s Eve. The play was successfully staged in several theaters across the Soviet Union, and in 1975, the idea emerged—much like in the case of the 1958 operetta—to adapt the work for the screen. This time, however, the remediation of the popular story occurred not through cinema, but through television. The result was not a movie musical (as with the 1962 film), but rather a television film enriched with numerous musical interludes. Following its television premiere in 1976, the film quickly gained immense popularity [16]. It soon became an integral part of the semi-official New Year’s Eve ritual in the USSR, alongside champagne, caviar, the chiming of the Moscow Kremlin clock, and the now-traditional collective TV viewing.

The film opens with a brief satirical cartoon, created by Vitaly Peskov—himself a resident of a newly built neighborhood in Cheryomushki—that pokes fun at the uniformity of Soviet housing designs and the monotony of identical city blocks. Against this backdrop, the main narrative unfolds, telling the story of an accident that unexpectedly intertwines the lives of two seemingly incompatible people: Zhenia, a Moscow doctor, and Nadia, a Leningrad schoolteacher. Despite the absurd premise, viewers are drawn in by the fairy-tale quality of their blossoming relationship, a narrative of serendipitous happiness. At the same time, the film gently mocks the standardization pervasive in Soviet urban planning—identical buildings, streets, and even interchangeable apartment keys across different cities—a satirical motif that resonated deeply with Soviet audiences accustomed to the suppression of individuality. The lyrical songs, set to poems by Yevgeny Yevtushenko and Bella Akhmadulina and performed by Sergei Nikitin and Alla Pugacheva, quickly became as iconic as the film itself, imbuing the story with a distinct atmosphere of nostalgia and Soviet romanticism.

This film, unlike the earlier musical and the operetta set to Shostakovich’s music—which continues to be staged in musical theaters—has largely lived its life on television, with only rare cinema screenings [17]. Across the works of Soviet media culture that engaged with the housing issue, the shift in emphasis between 1962 and 1975 is striking. Although the central plot in both cases revolves around romantic entanglements unfolding against the backdrop of mass-produced architecture, the characters’ attitudes toward their environment change profoundly. In the 1962 film, we still see optimism and faith in the transformative potential of Soviet modernity. By 1975, however, irony and sarcasm dominate, leaving little space for the once-prevailing ideology of unshakable Soviet optimism. The mediatization of the “housing issue” in the USSR thus traces a broad arc: from the critical portrayals in literature and the widespread negative perception of communal living in the 1920s and 1930s, through the euphoria and hopeful optimism of the 1960s—when many Soviet citizens finally acquired private housing—to the growing disillusionment of the 1970s, when it became clear that the promised dream of communism could not, in itself, deliver happiness. Even in the 1980s, the housing problem persisted, as millions remained in need of adequate or improved living conditions. Ultimately, the “housing issue” in the USSR would remain unresolved until the very collapse of the Soviet state in 1991.

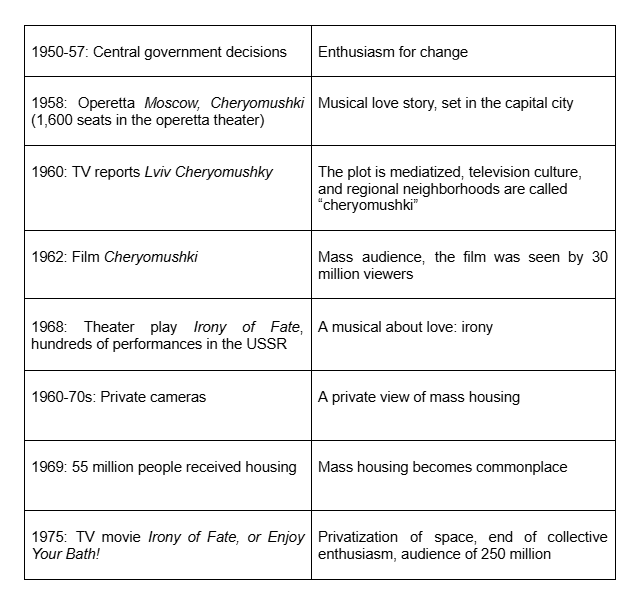

The table below illustrates how the mediatization of the “housing problem” unfolded in the USSR. In the 1950s, Soviet government decisions led to the construction of the experimental Cheryomushki district and the creation of a musical performance dedicated to the theme of housing. While the performance enjoyed great popularity, its reach was limited to tens of thousands of spectators in the Soviet capital. Nevertheless, the government’s “messages” found receptive audiences across the broader peripheries of the Soviet empire, and by the early 1960s, cities throughout the USSR began developing their own “cheryomushki” districts. The adaptation of the stage musical into a film marked the next step in the mass mediatization of the housing issue, allowing it to reach a far wider audience. By 1975, a similar remediation occurred when a popular theatrical performance was transformed into a television film, broadcasting the narrative to nearly the entire Soviet population. Yet by this stage, the initial enthusiasm for mass housing construction had begun to fade, giving way to growing disappointment and pessimism: the socialism promoted by the authorities could provide an apartment, but it could not guarantee happiness.