However, it was not party officials who held the highest incomes, despite appearances. The top earners were actually the heads of enterprises, factories, and plants. For instance, in 1952, the director of the R. Luxemburg Knitting Factory in Kyiv earned a salary of 1,500 rubles, while the head of a workshop at the Voroshylovhrad Locomotive Plant received 2,000 rubles. By 1954, the director of the Kharkiv Hammer and Sickle Plant was earning 3,000 rubles. Although these salaries were comparable to those of middle-level party nomenklatura, the latter did not benefit from financial privileges like “pay in an envelope”; instead, production workers often received bonuses that were frequently equal to their salaries. For example, party nomenklatura member Oleksandr Liashko dreamed of purchasing a Pobeda car, while Petro Shelest, the director of the Kyiv Aviation Plant, was able to buy it using his annual salary and bonuses.[8] Business leaders managed scarce resources—particularly valuable in the post-war context—and often exploited their positions by forming informal relationships with partners for personal gain.

Compared to ordinary citizens, the financial situation of the ruling nomenklatura was relatively favorable. For instance, in the mid-1950s, a first-year student at a medical or agricultural university received a scholarship of 220 rubles. In contrast, a “Stalinist scholarship holder” at Taras Shevchenko State University of Kyiv in 1951 received 780 rubles. A university lecturer with a degree or an associate professor earned 2,000 rubles in 1949. In 1954, an accountant at the Vasylkiv Executive Committee in Kyiv Oblast earned 450 rubles, while his cleaner received 225 rubles. By 1955, the average salary in the Soviet Union was 711 rubles, with agriculture averaging 458 rubles, healthcare 521 rubles, and industry 807 rubles [9].

The financial remuneration of the nomenklatura alone does not provide a complete picture of their economic security; the prevailing price scale is also a crucial factor. In the first half of the 1950s, the prices of certain goods were as follows: a liter of oil cost 20 rubles and 20 kopecks, semi-smoked sausage was priced at 30 rubles and 70 kopecks, an annual subscription to a regional newspaper cost 60 rubles, a men’s woolen suit was 241 rubles, a women’s suit was 354 rubles, a carpet could reach 5,000 rubles, and a Pobeda car was priced at 16,000 rubles. The monthly fee for a place in a student dormitory was 10 rubles. However, state retail prices often served a symbolic role in the context of chronic shortages, as many people were compelled to purchase goods at significantly higher prices on the black market. Additionally, family budgets were strained by mandatory “loans to the state budget,” which could range from 500 to 1,000 rubles or more per year.

The privileges of the nomenklatura were evident not only in their substantial remuneration, including personal pensions, but also in their access to desired goods and services. For high-ranking officials, shortages and speculation were largely peripheral concerns; they ordered clothing and shoes from specialized workshops, enjoyed inexpensive meals and select products in official canteens, and spent their holidays at sanatoriums and official dachas. While ordinary citizens envisioned communism as a system of prosperity and selflessly worked to build it, the nomenklatura, with their privileges, were already living within that reality.

The death of Joseph Stalin on March 5, 1953, marked a significant turning point for the Soviet Union. The country’s new leader, Nikita Khrushchev, shifted the focus of both domestic and foreign policy, as well as governance methods. He moved away from Stalin’s mobilization and repressive model, in which substantial financial privileges acted as a “sweet carrot” to balance the “ruthless stick of purges.” Khrushchev aimed to implement a more competitive and prestigious model, requiring the nomenklatura to demonstrate their effectiveness and be content with their status. The liberalization of the political regime and the reduction of mass repression diminished the fear for their lives, which had previously been the primary motivator for diligence among high-ranking officials. This abandonment of the “stick” naturally led to a decrease in the “carrot” of a substantial temporary allowance.

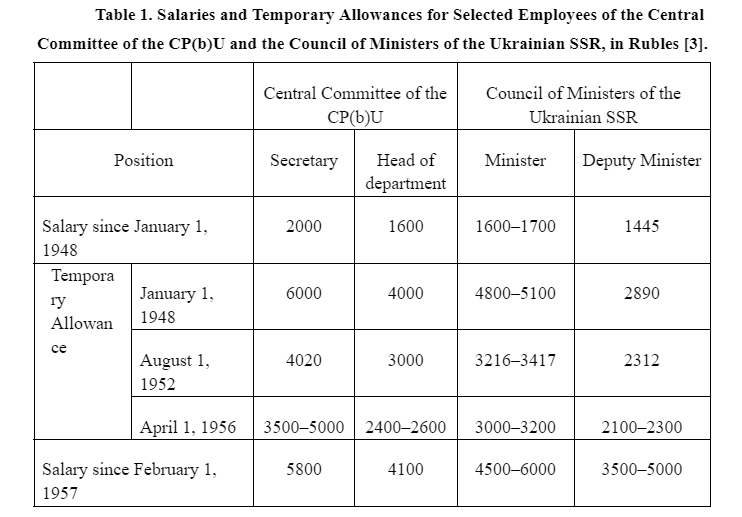

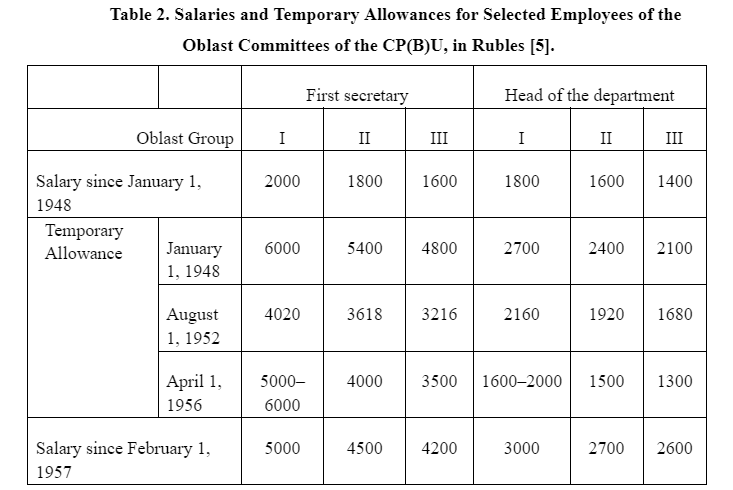

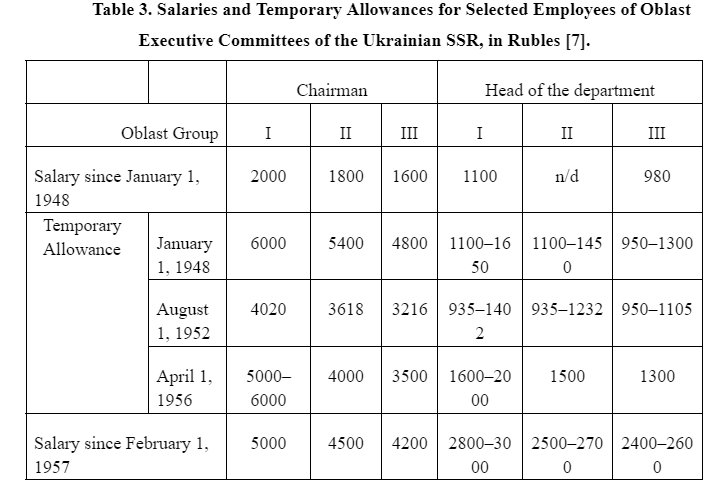

In an effort to enhance the efficiency of the governance system, Nikita Khrushchev advocated for a reduction in the size of the administrative apparatus and a decrease in its costs. On March 16, 1956, the CPSU Central Committee transferred the authority to determine the amount of temporary allowances for the party nomenklatura exclusively to the party’s Central Committee, excluding the government from this decision. As a result, several Central Committee members had their allowances canceled and instead received a “special allowance” amounting to about 80% of their salary. In April 1956, the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine mirrored this decision. Consequently, consultants, as well as heads of sectors or groups, were allotted a supplement of 850 rubles, down from the previous 1,062 rubles. The CPSU Central Committee established both the upper and lower limits of these allowances, with the final amount contingent on the nomenklatura’s family composition. For instance, while an instructor of the Central Committee was eligible for 2,400 rubles in 1952, the 1956 guidelines set the limits at 1,600 to 1,800 rubles. Thus, inspector Mykyta Tolubeyev, with a family of five, received 1,800 rubles, while Vasyl Taradaiko, with a family of four, received 1,700 rubles.[10] At the same time, the overall amount of financial privileges was slightly increased, likely reflecting Khrushchev’s desire to solidify his position on the political stage by garnering support from the nomenklatura following his exposé speech at the XX Congress of the CPSU in late February 1956.

Oleksandr Liashko, the secretary of the Donetsk oblast committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine in the mid-1950s, acknowledged in his memoirs that, despite not being able to save much money due to financial support from relatives, “our family was considered relatively well-off at that time.”[11] Temporary allowances enabled the upper echelon of the nomenklatura to live quite comfortably. Liashko’s family, with his wife working as a teacher, was more of an exception than the norm; most wives of high-ranking officials, who benefited from “pay in an envelope,” did not engage in employment. For instance, in early 1956, none of the wives of the secretaries from the Voroshylovhrad, Kirovohrad, Lviv, and Chernihiv oblast committees held jobs. Among the 19 individuals receiving temporary allowances in the Poltava oblast committee, only four wives were employed. In the Dnipro oblast committee, out of 25, twelve wives worked; in Odesa, nine out of 25; and in the Stalin oblast committee, eleven out of 26. This lack of employment among wives was clearly not due to difficulties in finding jobs, but rather to the families’ considerable wealth and the absence of a necessity for them to work, which further highlighted their elevated social status.

Following the 20th Congress of the CPSU, which opened avenues for limited public criticism of Stalin, discussions began to extend beyond the critique of his “cult of personality.” Disoriented by this unexpected shift in attitudes toward the “father of nations,” the public increasingly voiced concerns regarding the shortcomings of the current leadership, criticizing their management methods, reprisals against dissent, immoral behavior, privileges, and more. On March 28, 1956, during a party meeting at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Ukrainian SSR, Ivkin expressed his indignation that “the leadership has many dachas, receives large salaries, and occupies good apartments, which cannot be said of many workers and employees.” [13] Even bolder in his critique of the elite lifestyle of the nomenklatura was Borys Shcherbyna. At a closed party meeting of the Kyiv State Pedagogical Institute of Foreign Languages, he directly pointed out the privileged status of the leaders of city and oblast party organizations, as well as the Central Committee: “They are separated from the people by a guard of several individuals, receive not only salaries but also ‘pay’ in envelopes that are several times larger than their official salaries—payments for which they do not pay membership fees or taxes. They obtain food at wholesale prices, utilize special workshops, and attend theaters free of charge, not only for themselves but also for their wives, who usually do not work and have domestic staff. All of them have dachas surrounded by restricted zones, which cost a considerable amount of money to secure.” [14]

Ultimately, influenced in part by public criticism of the nomenklatura’s lifestyle expressed during the discussion of the “cult of personality,” the financial privileges of the nomenklatura were abolished. On January 29, 1957, the CPSU Central Committee and the USSR Council of Ministers officially rescinded temporary allowances and established new salary rates. In February of the same year, the Central Committee of the CP(b)U and the Council of Ministers of the Ukrainian SSR independently reaffirmed these resolutions.

The rationale for canceling the temporary allowance was rooted in the disparity in remuneration among various categories of apparatchiks. The CPSU Central Committee paternalistically invoked social justice, a principle it had undermined a decade earlier. The significant inequality was an objective concern even within the government, let alone on a national scale. However, the 1957 decrees did little to resolve the issue of inequality; the new salary rates were only marginally lower than previous earnings, including temporary allowances. Party and Soviet officials retained approximately 80-90% of their prior compensation. Temporary allowances were reclassified from a privilege into a legitimate component of salary, recognized as a financial reward for work. Efforts to strip high-ranking officials of their privileged financial status and to equalize citizens’ rights faltered by the end of perestroika. Brezhnev’s era of “stagnation” primarily signified stability for the nomenklatura: a predictable personnel policy, enhanced official comforts, and a tolerance for misconduct.

Thus, in the Soviet Union, two contrasting realities existed. One reality was inhabited by representatives of the authorities, whose well-being was directly linked to their integration within the political system. The allure of attractive privileges fostered loyalty to the regime. Through rose-colored glasses, the nomenklatura perceived the other reality, where ordinary people, balancing work and the struggle to meet their basic needs, sought moments of joy and clung to illusions of an impending “just” communism.

List of sources and references:

[1] Matthews, M. (1978). Privilege in the Soviet Union: A study of elite life-styles under communism (pp. 19–21).

[2] Central State Archive of Public Associations and Ukrainian Studies. File 1, Inventory 24, Case 4869, Pages 42-43.

* In the Central Committee of the CP(b)U, the privileged cohort included secretaries and their assistants, heads of structural units and some of their deputies, consultants, and inspectors, as well as the secretary and members of the party board. In the government, this group encompassed the head and his deputies, advisers and consultants, heads of structural units, and certain deputies, along with the heads and deputies of ministries, departments, and administrations. Within the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR, the head and his deputies, their advisers and consultants, as well as heads of structural units and some deputies, were also included. At the oblast level, the executive committees granted privileges to chairmen and their deputies, secretaries, and heads of structural units, along with chairmen of oblast courts and commissioners of the Ministry of Foreign Trade. This also extended to chairmen of city executive committees in oblast centers, the chairman of the Kyiv city executive committee, and its secretary and department heads. In oblast committees, secretaries, heads of structural units, and some deputies were financially supported, as were the first and second secretaries, secretaries, and department heads of the Kyiv city committee. Editors of republican and oblast newspapers, rectors of higher and oblast party schools, directors of branches of Lenin museums, secretaries of the Central Committee, oblast committees, and the first and second secretaries of the Kyiv city committee of the Leninist Communist Youth Union of Ukraine also belonged to this privileged group.

[3] Central State Archive of Public Associations and Ukrainian Studies. File 1, Inventory 16, Case 84, Pages 10, 49, 51–53, 121; Case 78, Pages 75, 83; Case 85, Pages 30, 42.

[4] Russian State Archive of Social and Political History. File 17, Inventory 121, Case 638, Page 50.

[5] Political leadership of Ukraine [Политическое руководство Украины], pp. 153; Central State Archive of Public Associations and Ukrainian Studies. File 1, Inventory 16, Case 78, Pages 86, 88, 90; Case 84, Pages 16, 19, 27, 35; Case 85, Pages 31. Arkusha, O. H., Boyko, O. V., Borodin, E. I., Motrenko, T. V., & Smoliy, V. A. (Eds.). (2009). History of civil service in Ukraine: In 5 volumes [Історія державної служби в Україні: у 5 т.] (Vol. 5, Documents and materials. Book 1. 1914-1991; G. V. Boryak, L. Y. Demchenko, & R. B. Vorobey, Eds.). Nika-Centre, pp. 553.

[6] Baran, V. K. (2011). Ukraine in the first postwar decade [Україна у першому повоєнному десятилітті]. In V. M. Lytvyn (Chair), H. V. Boryak, V. M. Heets, & others (Eds.), Economic history of Ukraine: Historical and economic research [Економічна історія України: Історико-економічне дослідження: в 2 т.] (Vol. 2, p. 398). National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, Institute of History of Ukraine.

[7] Vasiliev, V. Y., Podkur, R. Y., Kuromiya, H., Shapoval, Y. I., & Vainer, A. (2006). Political leadership of Ukraine, 1938-1989 [Политическое руководство Украины. 1938–1989]. Moscow: Russian Political Encyclopaedia, p. 153; Central State Archive of Public Associations and Ukrainian Studies, File 1, Inventory 16, Case 78, Pages 79, 80, 81; Case 84, Pages 59, 67, 79, 97; Case 85, Pages 45, 47, 49; Central State Archive of Higher Authorities and Governments of Ukraine, File 2, Inventory 8, Case 10235, Page 11.

[8] Baran, V., Mandebura, O., & others. (Eds.). (2003). Petro Shelest: ‘The real judgement of history is still ahead’. Memoirs, diaries, documents, materials [Петро Шелест: «Справжній суд історії ще попереду». Спогади, щоденники, документи, матеріали] (Y. Shapoval, Ed.). K.: Genesis, p. 106.

[9] Rogovaya, E. Yu. (2003). Soviet life, 1946-1953 [Советская жизнь. 1946–1953 гг.]. Moscow, p. 501-502.

[10] Central State Archive of Public Associations and Ukrainian Studies. File. 1, Inventory 16, Case 168, Pages 35–36.

[11] Lyashko, A. P. (1997). Cargo of memory: Trilogy: Memories [Ляшко А.П. Груз памяти: Трилогия: Воспоминания] (Book II: Way to the nomenclature [Кн. II: Путь в номенклатуру]). Kyiv: Id ‘Delovaya Ukraina’, p. 246.

[12] Central State Archive of Public Associations and Ukrainian Studies, File 1, Inventory 24, Case 4435, Pages 12–87.

[13] Central State Archive of Public Associations and Ukrainian Studies, File 1, Inventory 24, Case 4255, Page 179.

[14] Central State Archive of Public Associations and Ukrainian Studies, File 1, Inventory 24, Case 4255, Pages 71–72.

Questions for Discussion:

- What arguments did the apparatchiks of the Kharkiv regional committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine present to the Party Control Commission to advocate for an improvement in their financial situation?

- Why were there disparities in remuneration between party and Soviet officials and between employees of ministries and departments in similar positions across the USSR? What factors influenced this hierarchy?

- According to O. Liashko, Khrushchev referred to temporary allowances as “bribery.” Do you agree with this characterization of financial privileges?

- Khrushchev, as the leader of the USSR, was known as a fighter against Stalin and bureaucracy, striving to make the Soviet management system more dynamic (for example, through the liquidation of ministries, the creation of sovnarkhoz [Regional Economic Soviet], the restructuring of the party based on production, and the introduction of rotation). Why was he cautious about reducing the monetary allowances of the nomenklatura in his attempts to improve management and personnel?

- What factors contributed to the significant disparity in financial remuneration between the elite and the rest of Soviet society?

- Most documents regarding the financial privileges of the nomenklatura were classified as “top secret” and remained unpublished during the Soviet era. Why were these privileges shrouded in secrecy?

Cover image: Registration of Candidates, State Archives of Lviv Region Collection, Urban Media Archive

Translation into English: Yuliia Kulish