Bibliography:

[1] Pokrovskyi Historical Museum. Documentary Collections, KN – 4950 / KPBG – 963, Manuscript [Pokrovskyi istorychnyi muzei, dokumentalni fondy, КН – 4950 / КПБГ – 963, rukopys] (Zhelezniak M. N. Autobiography of Mark Nikitovich Zhelezniak, written in his own hand in 1967 [Avtobiografiia Marka Nykytovycha Zhelezniaka napysana yoho sobstvennoyu rukoyu v 1967 rotsi]).

[2] Zaliznyak, Volodymyr. With the Guardian Angel and Photography through Life [Z anhelom-okhorontsem i foto po zhyttiu]. Kyiv: Dukh i Litera, 2018.

[3] “Results of the October Photo Contest on the First Theme” [Rezultaty oktiabrskoho fotokonkursu po 1-i temi]. Sovetskoe foto, no. 2 (1929): 48–50.

[4] Sartorti, Rosalinde. “Photoculture II, or ‘Faithful Vision’ [Fotokultura II, abo ‘vernoe videnie’]”. In Soviet Power and Media [Sovetskaia vlast i media], edited by Hans Günter and Sabine Hänsgen, 145–163. St. Petersburg: Akademicheskii proekt, 2006.

[5] A Soviet avant-garde photographer, he criticized the established approach to photography from the position of “camera on the stomach” and sought unusual angles, from bottom to top and top to bottom. (Rodchenko, Alexander. “Ways of Contemporary Photography [Puti sovremennoi fotografii].” Novyi LEF: Journal of the Left Front of the Arts [Novyi LEF: Zhurnal levogo fronta iskusstv], no. 9 (21) (1928): 31–39).

Marko Zalizniak (1893–1982) was a rural amateur photographer best known for his images from the front lines of World War I and for documenting collectivization in the villages of what is now the Pokrovskyi District of Donetsk Oblast, Ukraine. The opening of a primary school in his home in the Romanivskyi khutir in 1927 can be seen as a prologue to his 1929 competition photograph, which will be discussed below. The following year, the residents of the khutir decided to construct a separate school building at their own expense. The new school opened in 1928, timed to coincide with the 11th anniversary of the October Revolution. Soon afterward, the Soviet authorities took the building under their jurisdiction and assigned a teacher and a cleaner to the school. Children from neighboring khutirs began attending classes there [2].

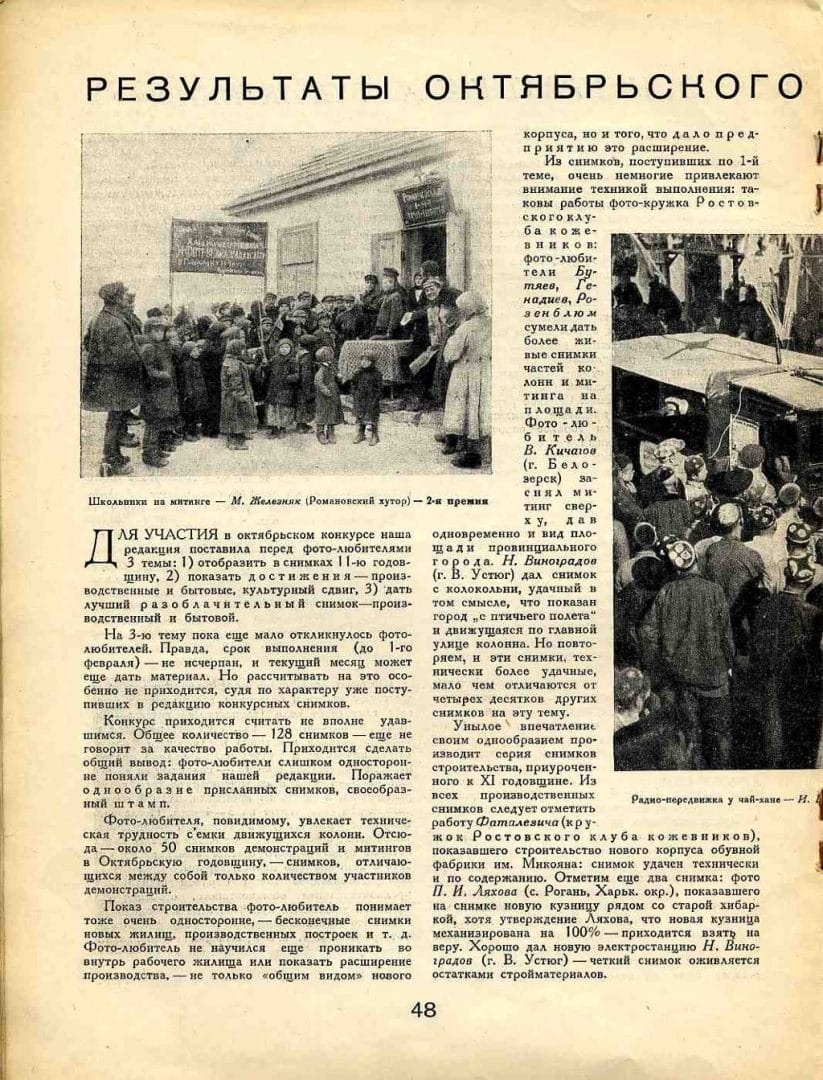

At the grand opening, a local photographer captured a scene of children and adults holding a banner with a slogan characteristic of the Bolshevik rhetoric of the time: “Children of all countries, unite! Long live the 11th anniversary of October, which brought education to this remote corner.” He submitted the photograph to a contest announced at the end of 1928 by the editors of the magazine Soviet Photo (Sovetskoye Foto).

The magazine, launched in 1926 by the Ogoniok Publishing House, served as a printed platform for promoting photography among the broader population, thereby contributing to the creation of a so-called proletarian culture of amateur photography. By the late 1920s, it functioned not only as an ideological mouthpiece but also as a forum that embraced the then-fashionable progressive spirit of avant-gardism, engaging in debates over new forms of artistic expression within its pages. The magazine not only provided readers with guidance on the basics of photography, classic and alternative principles of composition, types of angles and shooting points, and instructions on how to construct equipment and cameras by hand, but also offered opportunities to take part in photo contests, correspond with the editorial board, learn about the latest technical innovations abroad, order chemical reagents, and obtain practical advice on how to establish a photography club in one’s city or village. Between September 1931 and January 1934, the publication appeared under the title Proletarian Photo (Proletarske Foto), before reverting to its original name. According to Zalizniak’s memoirs, he subscribed to Soviet Photo in 1927–28 and preserved his collection until the late 1960s, when he donated it to the local museum [1].

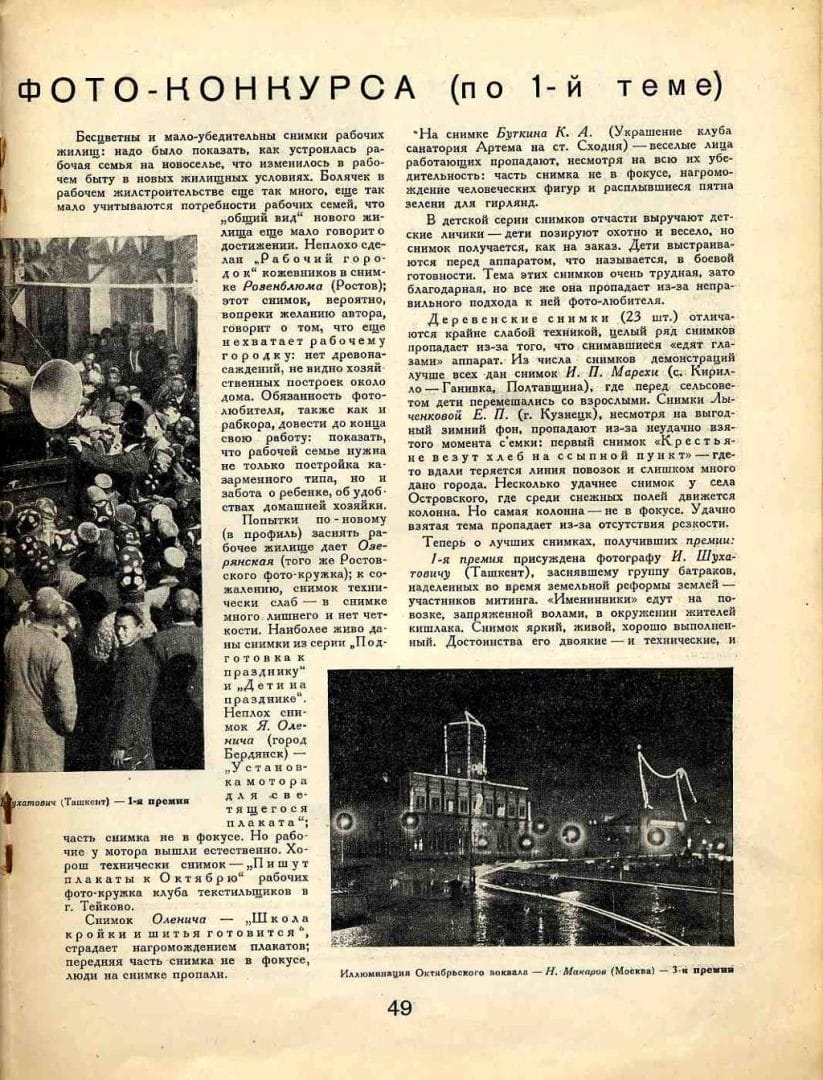

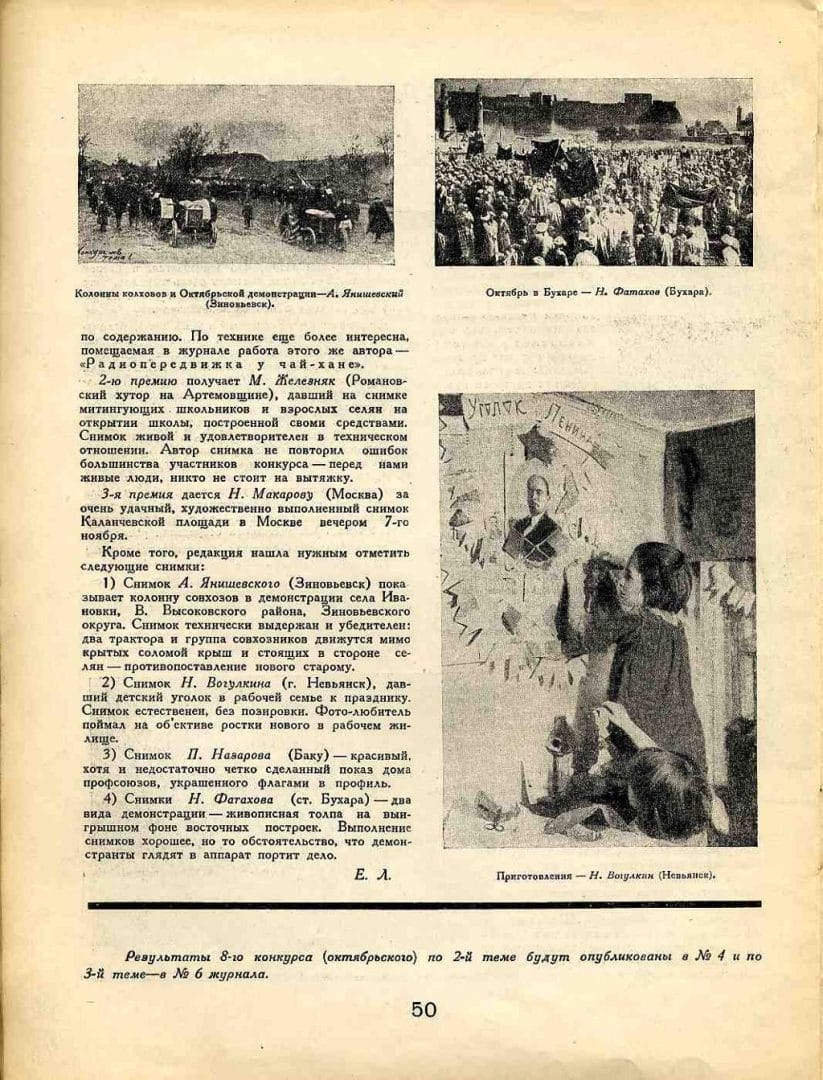

The photo contest was organized around three themes: the first celebrated the anniversary of the revolution; the second highlighted “achievements in production, everyday life, and cultural change after the revolution”; and the third aimed to expose “vestiges of the past” through critical depictions of production and daily life. In total, 128 photographs were submitted. However, the organizers deemed the contest largely unsuccessful, citing the monotony of the works and their generally low artistic quality [3, p. 48].

Zalizniak’s photograph won second prize in the first category and was published in the second issue of Soviet Photo in 1929 with the caption: “Schoolchildren at a rally — M. Zalizniak (Romanivskyi khutir) — 2nd prize.” Alongside the image, the editors added a note: “The second prize goes to M. Zalizniak (Romanivskyi khutir, Artemivsk region), who photographed children rallying and adult villagers at the opening of a school built at their own expense. The photograph is lively and technically competent. Unlike most contestants, the author avoided typical mistakes: we see real people, no one is standing stiffly at attention” [3, p. 50].

From a technical standpoint, the photograph suggests that Zalizniak concentrated primarily on documenting the event itself, paying less attention to innovation in its visual presentation. He photographed “from the navel—the camera on the stomach” ( by Alexander Rodchenko [5]), a position common at the time when cameras were typically held at waist or stomach level [4, p. 147]. Although the picture records an actual event, it does not exclude the possibility of partial staging. Alongside the school’s opening, Zalizniak also captures a carefully structured collective composition: the figures at the edges of the frame appear to bracket the image, while the central points of focus—the banner and the speaker behind the makeshift podium—are deliberately highlighted. The surrounding crowd serves largely to fill the space defined by these focal elements.

It appears that the photographer does not sharply distinguish between the event itself and the methods of representing it, working instead in a relatively straightforward manner. Perhaps for this reason, the competition organizers did not award the photograph first prize, although they clearly intended to encourage capturing the villagers from “remote corners.”