“[…] Olga Ilyinichna conscientiously fulfilled her duties as a member of our bureau and always submitted her documents on time. In both her work and her attitude toward me, I noticed no trace of seniority or the sense of superiority one might expect from an experienced party official from the capital—despite Shelest’s earlier warnings about it. Perhaps my firm demands on Senin¹, who had been late in preparing materials for the Presidium, played a role—after all, she worked closely with him and oversaw the same sectors of the economy. I treated her with respect, as a woman who had lost her husband in the war and raised two children on her own. By then, she already had grandchildren. Yes, her life had been difficult: she had endured a tough school of engineering and economic work at the factory—especially demanding for a woman. And yet, her character seemed more typical of a man’s.”

But one day, she surprised me with an act that only a woman—driven by pure feminine pride—could dare to do. She came to me holding a folder of papers. I stood up from the table and complimented her on how good and youthful she looked, especially in her new dress-suit, which suited her remarkably well. Compliments are always pleasant for women, and even more so for those nearing retirement age, as was the case with Olga Ilyinichna. And the dress truly was beautiful—expertly tailored from thick silk with an unusually intricate pattern, dyed in carefully chosen colors. Apparently, my unexpected compliment brought her such joy that she immediately told me everything about the dress’s origin.

“It’s the only one of its kind!” she exclaimed. “No one else has a pattern like this! The fabric was made at the Darnytskyi Silk Factory and sewn at the House of Models. By the way, where do your wife and daughter have their clothes made? I can introduce them to the best designers—they’re true craftsmen!”

“Thank you, Olga Ilyinichna, but they’ll manage on their own. You mentioned that no one else has a pattern like yours. Why is that? It’s such a beautiful design—you can clearly see the master’s hand in it.”

“As soon as they showed it to me, I immediately asked them to make fabric for a dress, and then to break up the printing board. Let them create new designs, but not repeat this one!”

I was taken aback by her revelation. She herself, it seemed, realized she had said too much.

“Do you understand what you’re saying, Olga Ilyinichna?” I asked, switching to a formal tone. “An artist and a carver worked on that design—and now their work is to be destroyed? For what? Just so no one else can have the same pattern? They’ll write it off as a production expense, and people will talk.”

I looked closely into her eyes and saw her face flush—not with shame for what she had done, but from the realization of her own imprudent candor.

“Oh, it’s just me… I was just talking nonsense, like women do,” Olga Ilyinichna began to excuse herself in a low voice. “No one actually broke the board, I’m sure. I will check, just in case…”

“I respect you, Olga Ilyinichna,” I said, “but I must warn you: if I learn of such actions—or anything like them—being committed by anyone, I will openly condemn them before the Presidium. I consider this unacceptable. Now, let’s get down to business.”

Trying to move past the sudden tension, I began reading aloud the draft resolution she had brought. After about an hour of working through the documents, we parted on a cold note. The conversation remained between us, but the sense of mutual trust that had developed at the beginning of my work at the Central Committee was now replaced, on her part, with a degree of wariness.

Later at home, I told my wife about the unpleasant exchange, adding jokingly:

“You can expect trouble from a female leader just as much as from the wives of leaders. They operate according to their own logic.”

“And how much trouble have you had from me?” my wife shot back.

“None from you.”

“Exactly!”

I should note that during all our years living in Kyiv, neither my wife nor my daughter ever used the services of the House of Models. They had their clothes made in the Kommunar workshops, where all employees went.

If anyone reading this gets the impression that I am hesitant to promote women to leadership positions because of their character traits, that would be a mistaken conclusion. In fact, I will say more: throughout my many years in leadership roles, I have never once doubted the erudition, exceptional intelligence, and strong organizational skills of women. Even during my time as secretary of the oblast committee, I became convinced that when a collective farm had three or four chairmen but showed no improvement, a woman should be recommended for the position. In our oblast, there were six such women. They were elected from among agronomists and zootechnicians, and one was a local schoolteacher. These women pulled their farms out of the quagmire of debauchery and drunkenness that had taken hold, a problem that often began with the treatment of each newly elected chairman. Thanks to their leadership, these farms improved markedly and were honored with orders and medals. One of them, Lidiya Yurgen, chairwoman of the Karl Marx collective farm in the Selidovo district, was even awarded the title of Hero of Socialist Labor.

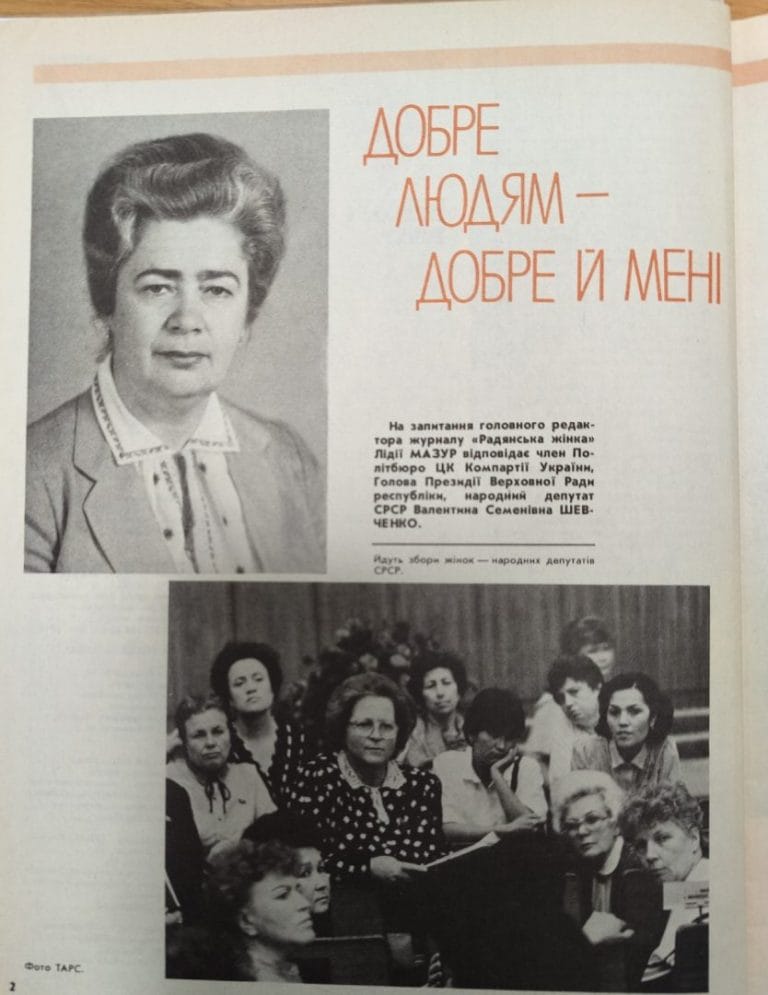

Here in Kyiv, I met many women who were directors of enterprises and organizations across various fields and cities, as well as party and Soviet officials. It was customary for one of the positions among the secretaries of oblast and city committees, deputy chairpersons of oblast, district, and city executive committees to be held by a woman. Many women also worked within the apparatus of the Central Committee, the Council of Ministers, the Supreme Council, ministries, and state committees. This personnel policy was actively pursued by party organs to involve women in public life. The Central Committee strictly ensured that women elected as people’s deputies made up at least one-third of the total number of deputies in the Supreme Council and in councils at other levels. Today, new democrats criticize this as an artificial regulation of the personnel composition of elected bodies. That is true, but perhaps someone knows a better way to guarantee the right of women—who comprise more than half of society—to participate in the work of state and political institutions?

Women who rose to leadership positions in government, public, and economic sectors performed their duties no worse than men. In fields such as public education and healthcare, they often held leading roles nationwide. We owe them, first and foremost, the high level of social and cultural life and the upbringing of the younger generation, which was admired throughout the world at that time.

[1] Ivan Semenovich Senin (1903–1981) was a party and state official in the Ukrainian SSR. He rose from working as a miner in 1917 to becoming director of the Ukrakabel factory in Kyiv from 1932 to 1937. Beginning in 1938, he held various government positions. From 1959 to 1965, Senin served as first deputy chairman of the Council of Ministers of the Ukrainian SSR. See: Lozitsky, V. S. (2005). Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine: History, personalities, relations (1918–1991) (p. 257). Kyiv: Geneza.

Oleksandr Liashko (1916–2002) had a distinguished career, rising from engineer to head of the Ukrainian government. In his memoirs, written shortly before his death, he offered a detailed account of the era, its administrators, and their governing practices. In 1963–1964, while serving as secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, Liashko worked closely with Olga Ivashchenko—one of only two women to serve on the Central Committee’s Politburo during its entire existence. The episode involving her, recounted in the excerpt below, was tied to the improvement of domestic services for the nomenklatura and, in its own way, reflects the character of Soviet-era governance