Good for People — Good for Me

Lidia MAZUR, editor-in-chief of “Soviet Woman”, interviews Valentyna Semenivna SHEVCHENKO — member of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, Chairwoman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Republic, and People’s Deputy of the USSR.

— Dear Valentyna Semenivna, we are speaking at a time when Soviet citizens are following the work of the Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR with exceptional interest — which is only natural. The fate of the country is dear to each of us, and everyone is concerned about the future of perestroika. In your opinion, how should we assess the Congress, the decisions it has taken, and how does its work differ from that of the highest state authority in previous convocations?

— First of all, I would note the nature and style of the Congress’s work — businesslike, demanding, and principled. I have participated in sessions of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR in previous convocations, and I must admit that there has never been such interest, such a wide range of views and approaches, and at the same time such heated discussions. This is good, because it is precisely in this way — without the former pomp and thoughtless “unanimity” — that serious state decisions should be made.

The Chairman of the Supreme Soviet, M. S. Gorbachev, General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and the Supreme Soviet of the USSR were elected in an engaged and collegial manner, in full accordance with constitutional requirements. By the time this magazine is published, readers will already know how the organizational issues were resolved, so I will simply say that I believe power has been entrusted to politically far-sighted, educated individuals with strong will, who are deeply aware of their responsibility to the people and to future generations.

At the same time, I would point out that, in my opinion, the Congress is not without excessive ambition, and there are instances when individual deputies conduct discussions on an overly emotional level. Today, more than ever, we need deep analysis of phenomena, including their interrelationships, and highly qualified solutions to every problem.

The Congress of People’s Deputies, taking place at a turning point in our difficult history, is an extremely complex, important, and multifaceted event. Therefore, frankly speaking, it is not easy to assess all aspects of its work at present, when it is necessary to consider even the smallest details. However, one characteristic feature should be emphasized: despite the diversity and ambiguity of opinions and judgments, no one at the Congress has questioned the policy of perestroika. Everyone supports it and is unanimous in this regard.

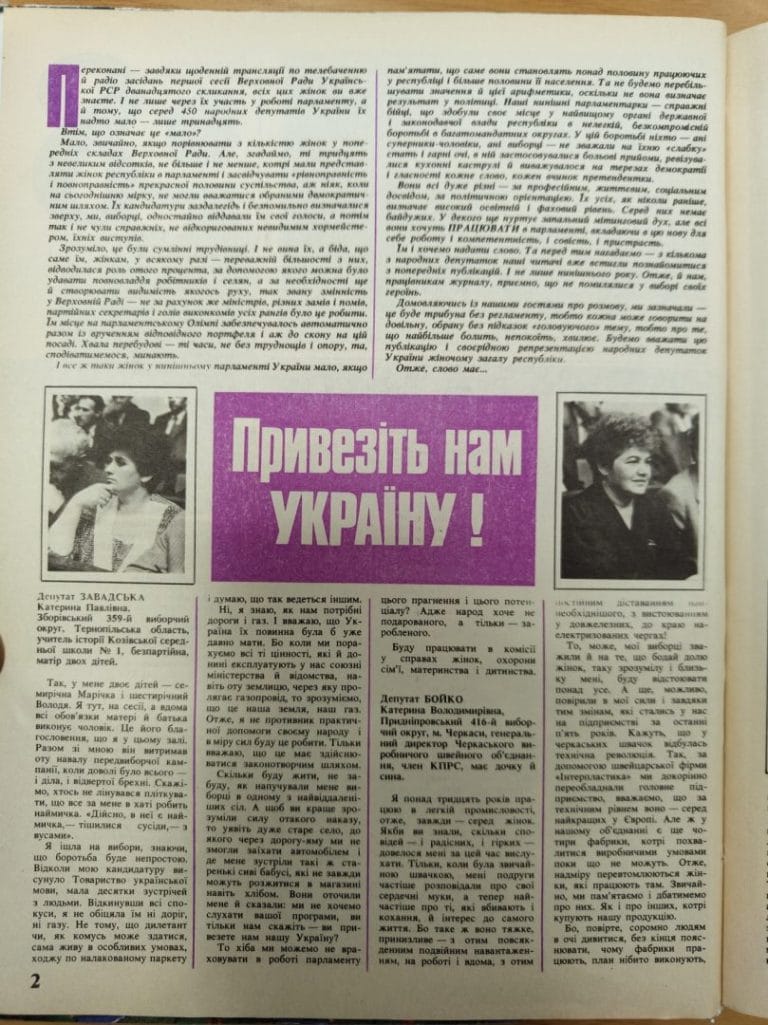

— Today, compared with previous years, there are only half as many women among the people’s deputies, even though they make up the majority of the country’s population and of those employed in public production, and have a higher level of education than men. In your opinion, does this reflect a realistic assessment of women’s role in the social and political life of the country, or is it rather the result of the fact that in the past we were not elected but, as they say, selected?

— During the recent elections, I witnessed the following incident at one of the polling stations. An elderly woman, shrugging her shoulders, muttered to herself: “How many times have I voted in my life, and this is the first time I’ve had to cross someone off the list…” Indeed, for the first time in many years, we have a real opportunity to choose — to choose from among alternative candidates — without the former organization and formalism. A fundamentally new situation has emerged in society, and while existing problems connected with the elections have become clearer, new ones have also appeared.

One of these is the representation of different groups of the population in the highest body of power. Workers, collective farmers, and young people received significantly fewer seats, and there are very few women among all categories of those elected.

Why did this happen? Some argue that certain shortcomings in the new electoral legislation came to the fore, while others point to the difficulty of applying it in practice. In the case of women specifically, some believe that their modest representation in the current composition of the country’s parliament is due to the fact that there are few real leaders among them…

But let us look at it more closely. How many women — and not only women — were truly prepared to vote and to stand for election? You may recall that Olexandra Vasylenko, an assembler at the Octava Production Association, and Valentyna Savchenko, a weaver at the Darnytskyi Silk Factory, were registered as candidates for the USSR People’s Deputies in the Minsk territorial constituency No. 467 in Kyiv. They were young, energetic, conscientious, experienced in public work, and well known in their work collectives. Yet neither received the necessary number of votes to win a seat in parliament. Why? I believe that the long-standing assumption played a decisive role: it was enough simply to “put someone forward,” and people would vote for them. In short, we were not ready to conduct campaigning and explanatory work under the new conditions.

As for women as leaders, government officials, or public figures, there remains a certain psychological bias in society — one that is not easy to overcome.

— Some people even believe, Valentyna Semenivna, that women should abandon competition, business, and political careers altogether, devoting themselves solely to their children and families.

— Should, shouldn’t… I am convinced that today we should first and foremost focus on creating optimal conditions in which women can fully realize themselves as individuals while remaining women in the highest sense of the word — mothers. The participation of women in public affairs is not a whim, nor merely a tribute to the principles of social justice upheld by our system, but an objective factor in the humanization of society and in the proper and competent development and selection of public policies. It is precisely their involvement in shaping party and state policy that enables women to ensure that the notorious “residual principle” does not extend, above all, to such vital areas of our life as health care and culture. Women will be able to make a positive impact only when they take part in resolving national issues and possess a comprehensive understanding of the economic and social situation on the ground.

— Elections for members of the parliament of our republic and local councils will soon take place. So, what conclusions should we draw? Is it worth fighting for “women’s” seats?

— We must seize every opportunity to ensure that women hold a worthy place in the new governing bodies of the republic. I emphasize once again: the more women there are in the councils, the greater the chances we will have to address specifically women’s concerns alongside all other important matters.

The elections for people’s deputies of the Ukrainian SSR and local councils, scheduled for next spring, will be conducted under the new republican electoral laws. Drafts of these laws, together with proposed amendments to the Constitution of the Ukrainian SSR, will soon be submitted for public discussion. I consider it fundamentally important that our women put forward their proposals and wishes regarding these new legislative acts, and that they approach them seriously, with a proper sense of civic responsibility.

Today, women themselves must recognize the urgency of the political moment. There is a broad field of practical activity for Soviet bodies, as well as for public, party, trade union, women’s, and youth organizations. But it is equally important that we skillfully promote female candidates and stand firmly in their defense.

— Valentyna Semenivna, in our republic, among those engaged in heavy physical labor, the so-called “fair sex” makes up 80 percent, and women also predominate among those working the third shift… Unfortunately, the list goes on. What, in your opinion, can be done about this? Perhaps we need new legislation?

— These problems are indeed acute and pressing, and they are not solely “women’s” issues but societal ones. I realize this may not please some of our female readers, but I will say it plainly: to a certain extent, these difficulties stem from our own passivity and insufficient legal literacy.

Under labor law, women are prohibited from working night shifts and may do so only on a temporary basis. Is this humane and fair? Yes. But it is another matter entirely how these and other protective provisions are interpreted and applied in practice. How many economic managers, at various levels, truly see female workers as more than a source of maximum productivity—often at any cost, including health, free time, and family well-being? I do not exempt myself from responsibility here.

But tell me—where are our trade unions, our labor councils, our prosecutorial oversight, our sanitary inspectors, our women’s councils?

We are all partly to blame for the struggles of mothers and homemakers, for the inadequate network of consumer services and the meager selection of consumer goods. Life is hard for a city woman, and even more so for a rural woman who has a plot of land, a household, and countless chores—yet is left to manage it all alone.

Women have little reason to be satisfied with their employment status. While nearly every second man with higher or secondary education holds a managerial post, only seven percent of women do. There are very few female ministers, department heads, or directors. Among the secretaries of the oblast party committees, again, only seven percent are women—despite the fact that women make up a third of the party’s membership. Does this reflect the principles of social justice? Let’s be honest—no!

It seems no one doubts the necessity and importance of recognizing and recommending a talented, qualified female engineer for the post of enterprise director, or an agronomist for the position of collective farm head. Yet this has still not become the norm. The decisions of the 27th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the documents of the 19th Party Conference stress that women should be actively promoted to leadership roles in economic and organizational work—at the level where decisions are actually made. In practice, however, these directives are not being implemented, and prejudice against women—this relic of a stagnant past—continues to persist. And we women, too, often fail to show the necessary persistence and interest.

To change this situation, substantial efforts are required from the state, from society, and from us, the women ourselves. We must achieve tangible progress in improving services and service quality, and we must accelerate the fulfillment of the five-year plan of measures aimed at improving women’s working conditions. This matter has been raised repeatedly in recent sessions of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR, in meetings of its Presidium, and in standing committee discussions.

One urgent task is to update existing legislation on benefits for women. I believe we need a union-level law on the protection of motherhood and childhood, one that would improve working and living conditions for women and mothers—extending paid maternity and childcare leave, shortening the working day, and more.

Even now, much can be done at the enterprise level. With self-financing in place, many enterprises have significant resources for social development. At the Trypilska Thermal Power Plant, for example, I learned that the labor collective council had decided to extend paid childcare leave for mothers of young children to three years. This is an excellent step, and such opportunities should be used more often. Of course, the question of preserving a mother’s length of service during this period must be resolved legislatively.

Strengthening women’s social protection is one of the points in my own program as a deputy. It includes measures to support those whose incomes fall below the so-called subsistence minimum: mothers with many children, soldiers’ widows, as well as certain categories of war and labor veterans and pensioners. It is gratifying that we have already succeeded in improving pension provisions for disabled veterans of the Great Patriotic War (3rd group), for participants in the war in Afghanistan, and for the families of fallen internationalist soldiers.

If we want a mechanism that genuinely guarantees women’s social protection, then we must improve coordination between political parties, state bodies, and labor collectives, and we must strengthen the contribution of trade unions, women’s councils, youth organizations, and other public groups to this work. In short, we need a strong, coherent, and—above all—effective state policy on women, for such a policy is the key precondition for women’s professional, intellectual, and political growth, and for enabling them to combine productive work with raising children and enjoying a full life.

— Valentyna Semenivna, it so happened that Soviet people are well acquainted with the biographies of foreign leaders, their hobbies and preferences, and even the virtues and flaws of their wives, children, and grandchildren. We often perceive our own leaders as if they were robots, with no interests beyond their official duties. But this is not the case.

So please, tell us about yourself. Is it difficult for a woman to be president? Do you sometimes envy your friends who are not burdened with such extremely difficult and responsible work? What songs do you sing? What is your favorite color? And finally, what do you think about women — not only as a woman yourself, but as a woman with unique experience as a political and public figure?

— To be honest, I have been asked these questions quite often lately. I believe this reflects not only traditional human curiosity, but also, quite clearly, a certain inner need to know as much as possible about one another. Still, when it comes to a person’s private life, regardless of their position or profession, one must always maintain a keen sense of proportion and tact.

I was born into a working-class mining family in Kryvyi Rih. That is where I received my first lessons in life, where I became accustomed to lean borshch, clumsy jackets, rubber boots, and healthy human relationships. Perhaps this has left its mark on my entire life, making me undemanding about the so-called benefits of life — something that is very helpful now that, as you say, I am president.

To say this job is not easy would be an understatement. There are so many responsibilities, and they are so complex and demanding, that I must work 12–14 hours a day, sacrificing weekends and even holidays. I want to understand everything, get to the bottom of everything, know what is happening in our republic and in the country, constantly maintain contact with my constituents, and help them solve their problems. My attitude towards life is this: good for people — good for me. I also try to keep abreast of international events and follow the latest developments in literature, theater, cinema, and fashion.

On top of all this, no one has relieved me of my duties as a wife, homemaker, mother, and, more recently, grandmother. Even though my son and daughter-in-law have their own family and life, as the saying goes, there’s no place like home. Besides, I always want and need to be in good working shape. So, judge for yourself whether it is easy to be president. As for whether I envy my friends — that is for each person to decide for themselves, or, more precisely, to build their own destiny. Sometimes I do envy them…

As for my preferences, since childhood I have loved historical prose and classical poetry. I am fond of Ukrainian folk songs, many of which I heard and remembered from my mother. My favorite color is green — the color of spring, of the first leaves, of grass; in a word, the color of life.

What do I think about women? To answer that fully, we would have to begin the conversation from the very start, because it is a serious topic. In short, I deeply respect women for their innate intelligence and inner beauty, for their ability to be faithful and to lend a shoulder at the last moment. Yet sometimes I want to feel fragile for a while, I want to see that, as Alexander Blok has neatly put it, servitude of men — in the highest sense of the word. And, by the way, if a woman is happy, a man is happy too.

FROM THE EDITOR. We received galley proofs from V. S. Shevchenko with the note: “I am proofreading this well past midnight. Everyone else is already resting, but I still have work to do. In the morning, I have new meetings, exchanges of ideas, reflections, plans. And they are waiting for me at home in Kyiv… June 8, 1989.”

Valentyna Shevchenko (1935–2020) had a distinguished Soviet political career. She began her professional path in 1954 as a school Pioneer leader in Kryvyi Rih. Three years later, she transitioned to work in the Komsomol, and later moved into Party structures. In 1962, she assumed the position of Secretary of the Central Committee of the Leninist Communist Youth Union of Ukraine (LKSMU). From 1975 to 1985, Shevchenko served as Deputy Chair of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR, and in 1985 she became its Chair — making her, under the 1978 Constitution of the Ukrainian SSR, the head of the republic’s highest state authority.

Her interview, published in the newspaper Soviet Woman, was recorded after the First Congress of People’s Deputies of the USSR, which took place in late May and early June of 1989. Thanks to the actions of opposition deputies, the congress turned into a striking political event. Both the questions posed by the magazine’s editor-in-chief, Lidia Mazur, and Shevchenko’s answers clearly reflected the influence of Gorbachev’s policy of “glasnost.”