Reporting from the Wide Road

Recently, I traveled with a traffic inspector.

I became acquainted with the cargo of service vehicles speeding along after a short Saturday workday outside Kyiv.

Frankly, I didn’t expect what I encountered.

Let me start from the beginning.

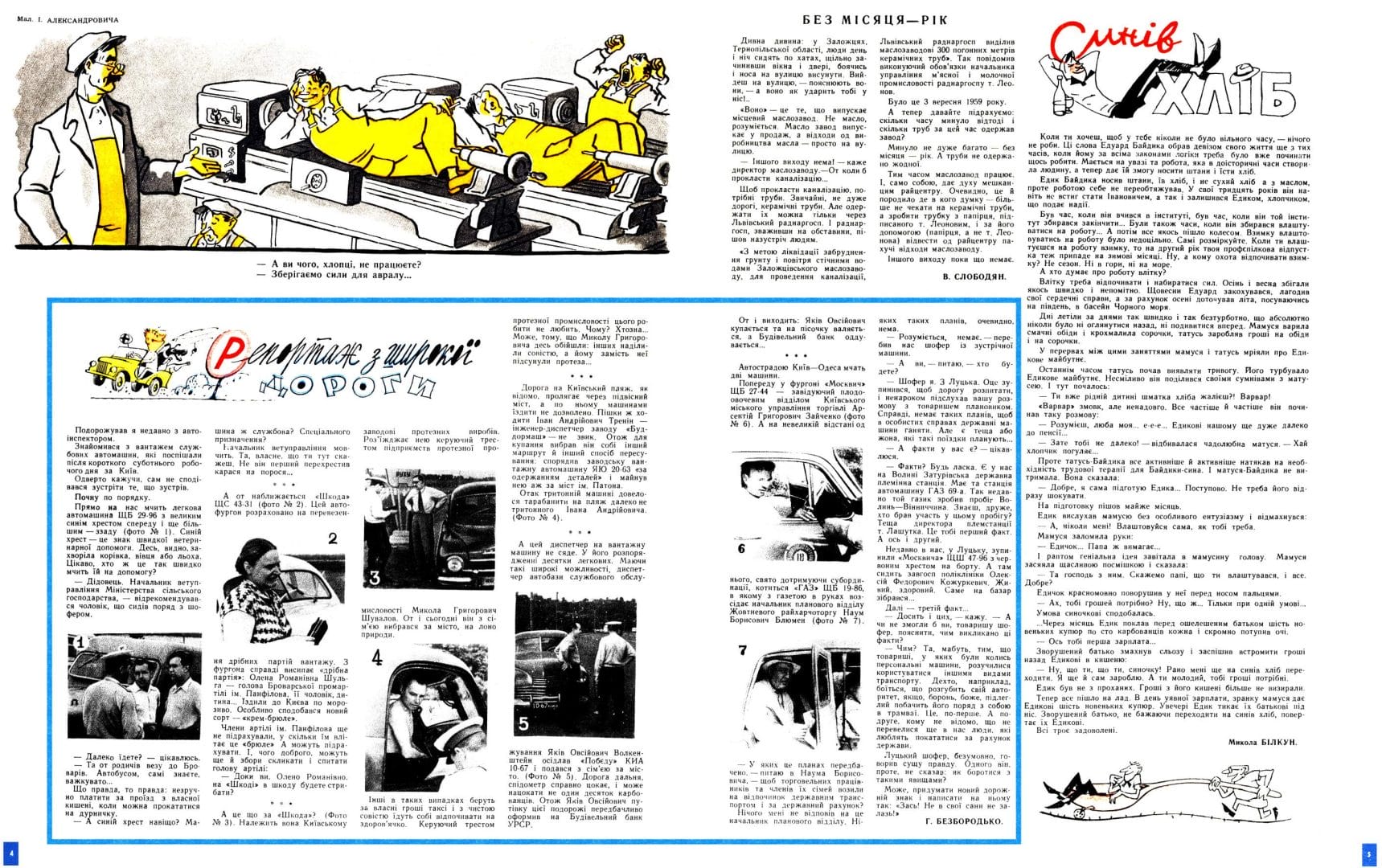

A passenger car with license plate ЩБ 29-96, marked by a large blue cross on the front and an even bigger one on the back, is coming straight toward us (photo 1). The blue cross indicates it’s an ambulance. Somewhere, it seems, a cow, sheep, or pig must have fallen ill. I wonder who is rushing to its aid so quickly?

“An elderly man. Head of the Veterinary Department of the Ministry of Agriculture,” introduces himself, sitting next to the driver.

“How far are you going?” I ask.

“Oh, I’m taking my relatives to Brovary. You know, it’s difficult to travel by bus…”

And it’s true; paying for transportation out of pocket is inconvenient when you can ride a state vehicle.

“What’s the blue cross for? Isn’t it supposed to be a special-purpose vehicle?” I ask.

The head of the veterinary department is silent. But, in fact, what can you say? He was not the first to cross a crucian carp into a pig…

The head of the veterinary department remains silent. But really, what could he say? He’s not the first to blur the line between public duty and personal convenience.

***

Soon, a Skoda with license plate ЩС 43-31 (photo 2) appears. This van is meant for transporting small cargoes. And “small cargo” is indeed pouring out of it: Olena Romanivna Shulha, head of the Panfilov Brovary Cooperative Artel, along with her husband and child. They went to Kyiv to buy ice cream. She especially likes the new crème brûlée flavor.

The artel members haven’t yet calculated the cost of this “brûlée.” But they could. And, who knows, they might even call a meeting to ask the head of the artel:

“How long, Olena Romanivna, will you keep hopping from Skoda to trouble?”

***

What kind of “Skoda” is this? (photo 3). It belongs to the Kyiv Prosthetics Factory, driven by Mykola Hryhorovych Shuvalov, head of the Prosthetic Industry Trust. Today, he and his family are headed out to nature. Others, in such cases, would take a taxi at their own expense. But the head of the prosthetic industry trust prefers not to. Why? Who knows… Maybe it’s because Mykola Hryhorovych missed out somewhere: others were given a conscience, and he was given a prosthesis.

***

The road to Kyiv Beach, as you know, crosses a pedestrian suspension bridge, where cars aren’t allowed. But Ivan Andriyovych Trenin, a dispatcher engineer at Buddormash, isn’t used to walking. So, he chose a different route, equipping the factory’s ЯЮ 20-63 truck “to pick up parts” and drove it across the Paton Bridge, bringing this three-ton truck, along with himself, whose weight is far from being three tons, down to the beach (photo 4).

***

Another dispatcher here wouldn’t even consider taking a truck. He has access to dozens of passenger cars. With such resources, Yakiv Ovsiyovych Volkenstein, dispatcher at the motor depot, hopped into his personal Pobeda, license plate КИА 10-67, and headed out of town with his family (photo 5). The trip was long, and the speedometer ticked up accordingly. So, Yakiv prudently applied for a voucher for the trip from the Ukrainian SSR Construction Bank.

Thus, Yakiv is swimming and lounging on the sand, while the Construction Bank foots the bill…

***

Two cars are racing along the Kyiv-Odesa highway.

Ahead, in a Moskvich van with license plate ЩБ 27-44, is Arsentii Hryhorovych Zaichenko, head of the Kyiv City Trade Department’s fruit and vegetable section (photo 6). Just behind him, in a GAZ ЩБ 19-86, is Naum Blumen, head of the planning department of Zhovtnevyi District Food Trade, observing all from the backseat with a newspaper in hand (photo 7).

“What plans are in place to transport trade employees and their families on public funds for their vacations?” I ask.

The head of the planning department doesn’t answer. Clearly, there are no such plans.

“Of course not,” interrupts the driver of the oncoming car.

“And who are you?” I ask.

“I’m the driver. From Lutsk. I just stopped to ask for directions and overheard you talking. Personally, I have no plans to use government cars for personal business. But I do have a mother-in-law who has her own ideas about these things.”

“Any examples?” I ask.

“Examples? Certainly. In Volyn, we have the Zaturivka State Breeding Station. It has a GAZ 69 car. Recently, it made a trip from Volyn to Vinnytsia. Do you know who traveled on that trip? The director’s mother-in-law, Mrs. Lashutka. That’s the first fact. Here’s another one: not long ago in Lutsk, we stopped a Moskvich, ЩШ 47-96, with a red cross on the side. Inside was Oleksiy Fedorovych Kozhurkevych, the head of the clinic, alive and well, on his way to the market… Need more examples?”

“That’s enough,” I said. “But, comrade driver, could you explain why such things happen?”

“Well, for one, some people used to owning cars forget how to use public transportation. Others worry they’ll lose authority if, heaven forbid, a subordinate sees them riding a tram. That’s one thing. And then, of course, there are those who still enjoy a free ride at the state’s expense.”

The driver from Lutsk certainly wasn’t wrong. The only thing he didn’t mention was how to deal with such behavior.

Perhaps it’s time to create a new road sign that says: “No! Don’t board a state vehicle for personal business!”

H. BEZBORODKO

The humorous and satirical magazine Perets, published (albeit intermittently) since 1922, served as a supplementary weapon for the government in its fight against social issues. Its editorial board frequently aligned with various official campaigns, wielding its sharp wit to expose violations, shortcomings, and vices, thereby shaping public attitudes.

Hryhorii Bezborodko, an experienced feuilletonist for Perets, often targeted the “antipodes of Soviet morality,” such as indifference, mismanagement, careerism, and other societal flaws. His report was no coincidence; it aimed to bolster the campaign against the misuse of official vehicles. Despite the 1959 restrictions on the use of state cars, members of the nomenklatura continued to exploit loopholes, necessitating public shaming rather than relying solely on legal enforcement. At its peak circulation of 250,000 copies, a publication in Perets could serve as a powerful catalyst for such public accountability.

The articles in Perets speak volumes about the scale of vehicle misuse among middle-ranking managers—such as department heads, supervisors of industrial artels, motor pool dispatchers, and trust managers—who wielded day-to-day authority and controlled significant resources. The documented cases reveal a pervasive habit of using official vehicles for private errands, a practice so entrenched that it outweighed the inconvenience of traveling in trucks or vans after the 1959 reduction in the official fleet.

The timing of the journalistic investigation was no accident. Conducted on a Saturday afternoon, it strategically eliminated any pretense by the caught officials that their private trips were necessary for business purposes. To heighten the impact of the exposé, the article was accompanied by photographs of the violators, graphically underscoring their breach of “state discipline.”