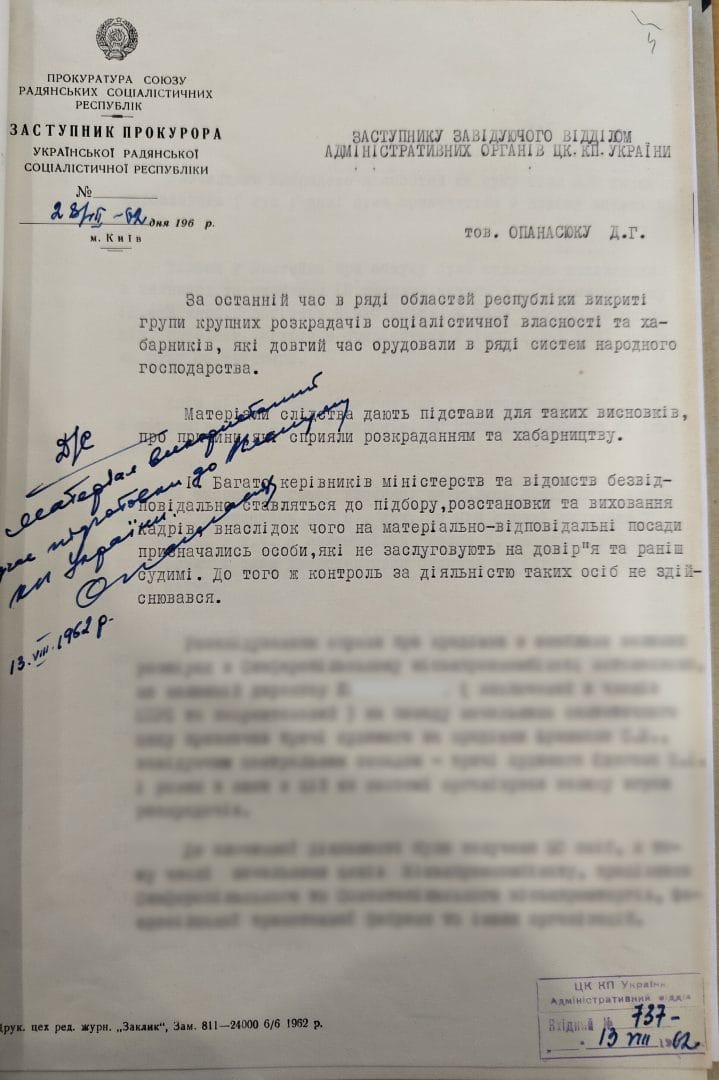

Information from the First Deputy Prosecutor of the Ukrainian SSR, M. Samayev, to the Deputy Head of the Department of Administrative Bodies of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, D. Opanasiuk, on “Exposed Groups of Large-Scale Embezzlers of Socialist Property and Bribe-Takers,” March 28, 1962 (Excerpt)

[…]

Instead of conducting a sharp and ruthless struggle against embezzlers, bribe-takers, and so-called “businessmen,” some employees of Soviet and party organs succumbed to self-interest, accepting handouts from criminals, participating in drinking bouts organized by embezzlers, and, as a result, becoming complicit in criminal activities themselves.

During the investigation into the case of former employees of the Kolomyia Curtain Factory (Stanislav oblast), including H. and others, it was revealed that H. had bribed several officials, engaged in drinking with them, and distributed handouts.

It was established that H. provided free tulle covers, bedspreads, and curtains to the former Deputy Minister of Light Industry of the Ukrainian SSR, Sh. Using the stolen money, H. organized drinking parties to which he invited Sh., the former secretary of the Kolomyia City Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, E., and others.

Evidence also showed that the wife of Y. received six curtains for windows from H. at the reduced price of 25 karbovanets each, while Y. himself accepted a piece of woolen fabric for a suit.

Additionally, H. bribed other officials with gifts. For instance, K., the head of the light industry department of the Stanislav state farm, was provided with custom-made curtains to match the color of each room in his apartment, along with tulle bedspreads, capes, and other products of the factory—all free of charge, as per H.’s instructions.

Moreover, H. supplied free factory products—curtains, bedspreads, carpets—to the chief engineer of the light industry department, B.; the chief accountant, V.; the auditor, Sh.; the former prosecutor of Kolomyia, O.; the former head of the Stanislav oblast financial department, F.; and others.

The investigation determined that H. and his accomplices had embezzled material assets worth 225,000 karbovanets.

Several employees of the curtain factory, interrogated as part of the investigation, testified that long before the case emerged, they had repeatedly reported thefts by H. and others to party and administrative authorities. However, these reports were met with superficial inspections, which failed to expose the perpetrators in time, allowing H. and his associates to inflict substantial losses on the state.

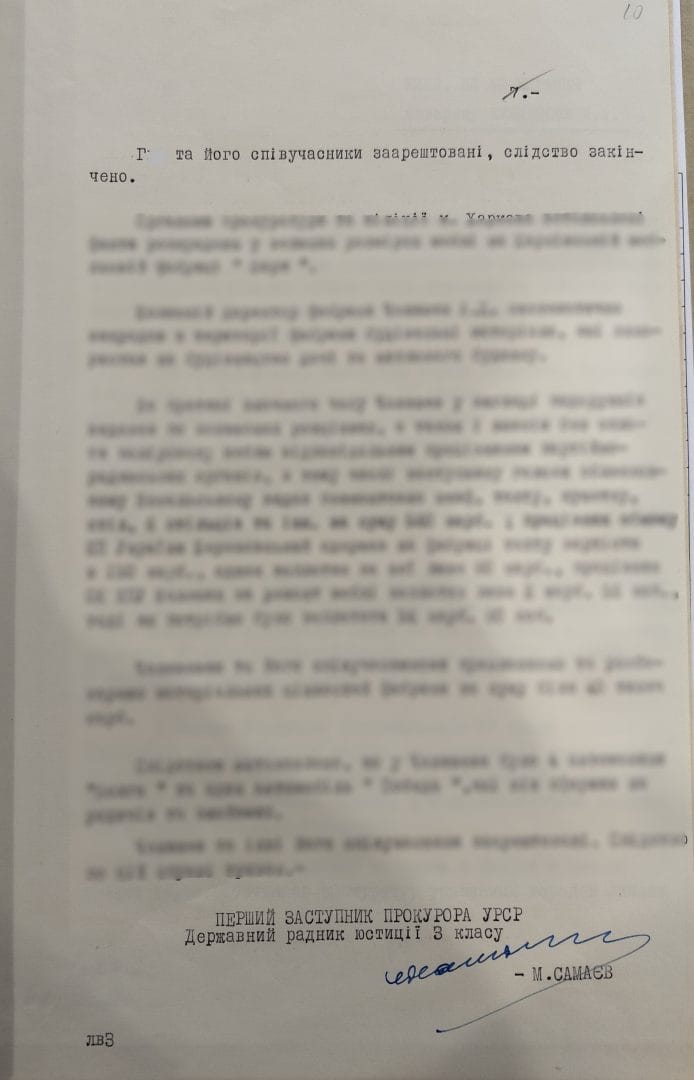

H. and his accomplices were arrested, and the investigation has been completed.

[…]

First Deputy Prosecutor of the Ukrainian SSR

State Counselor of Justice of the 3rd Class M. Samayev

*The names of the defendants in the case were anonymized by the researcher.

In the early 1960s, the Ukrainian prosecutor’s office reported to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine about “exposed groups of large-scale embezzlers of socialist property and bribe-takers who had long been operating within various sectors of the national economy.” The scale of the defendants’ shadow income was staggering: during investigations into four cases, authorities seized hundreds of thousands of rubles, single-story houses, kilograms of gold, dozens of cars, and other assets. Such wealth was enabled by a well-developed “shadow economy.” Despite inflated economic plans, strict resource controls, and rigorous oversight, resourceful producers consistently found ways to generate “surplus” production, which they used to enhance their own comfort and secure patronage. The anti-bribery campaign and crackdown on “plundering the people’s wealth” that unfolded in 1963–1964 achieved notable results.

Particularly striking was the prosecutor’s report to the Central Committee regarding abuses and bribery at the Kolomyia Curtain Factory in the Stanislav oblast (renamed Ivano-Frankivsk in 1962). The report detailed repeated “handouts” (bribes) given to certain city and oblast leaders, including the Deputy Minister of Light Industry of the Ukrainian SSR. Additionally, the theft of “material assets” worth 225,000 rubles—at a time when the average salary was less than 100 rubles—was astounding.

The nature of the bribes was also noteworthy: curtains, tulle, bedspreads, carpets, and “a piece of woolen fabric for a suit.” Although such items may seem trivial today, in the scarcity-driven Soviet economy, these everyday goods held as much value as money itself. Particularly striking were the custom-made “curtains to match the color of each room … of the apartment” of the head of the light industry department of the Stanislav State Farm. This detail reflected not only the official’s access to scarce resources but also a refined aesthetic taste.

Although M. Samayev, the first deputy prosecutor of the Ukrainian SSR, acknowledged the involvement of high-ranking officials in “criminal activity,” he limited himself to a legal assessment of the facts, carefully avoiding any political commentary. The report omitted any mention of accountability for the nomenklatura members implicated in these abuses. Most likely, they were punished “in the party order,” which typically meant a reprimand or, at most, expulsion from the party.