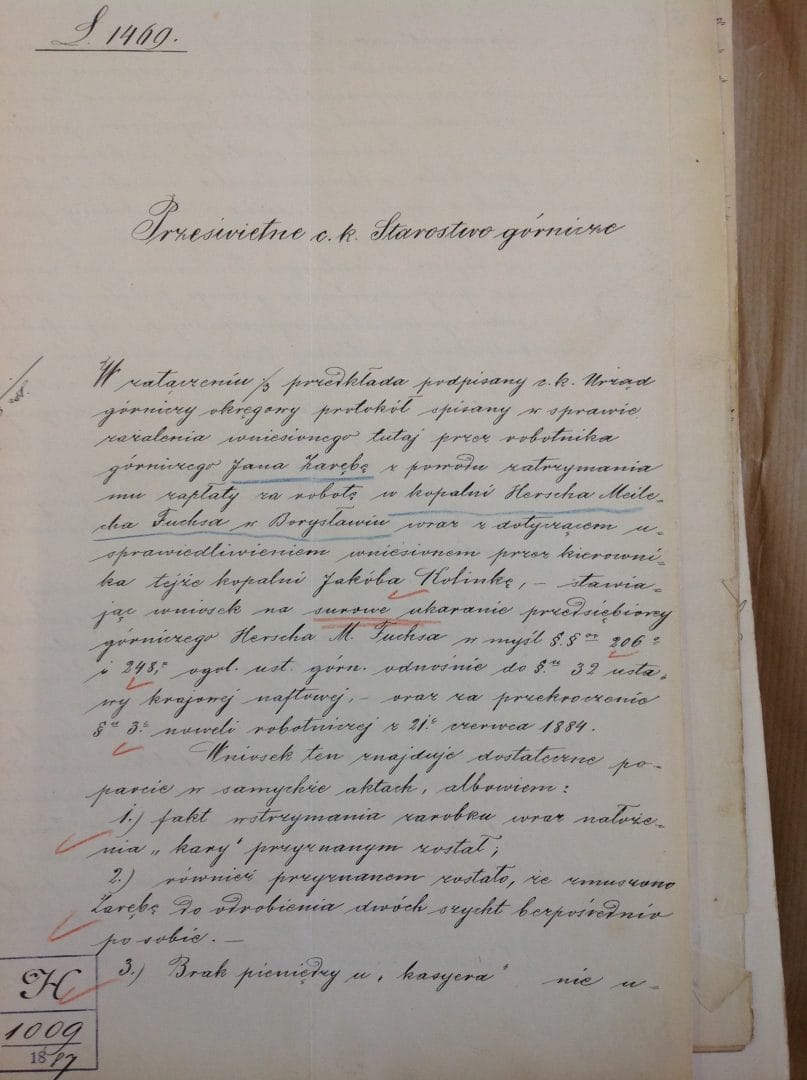

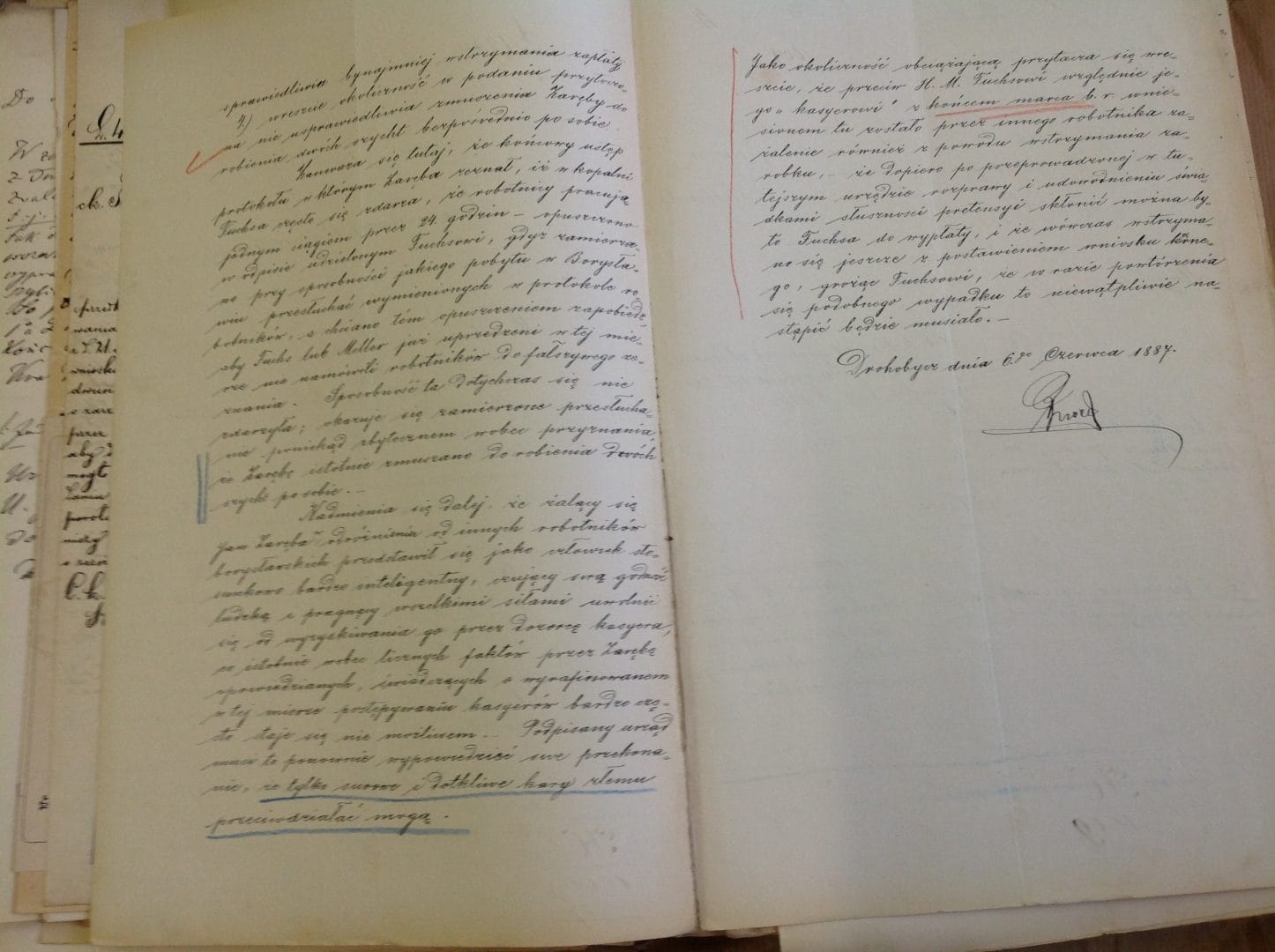

District Mining Office to the Cracow Mining Department, 1887 (National Archives in Krakow, collection 207, file 197)

(translation from Polish by Vladyslava Moskalets)

This protocol concerns the complaint filed by mining worker Jan Zaręba regarding the withholding of his wages for work at the Hersch Mielech Fuchs mine in Boryslav. Alongside this is the response submitted by the mine’s manager, Jakob Kolinka. The protocol puts forward a request for the severe punishment of the mining entrepreneur Hersch M. Fuchs, in accordance with Paragraphs 206 and 248 of the General Mining Law, and with reference to Paragraph 32 of the National Petroleum Law, as well as for violations of Paragraph 3 of the Workers’ Amendment of June 21, 1884.

This conclusion is sufficiently supported by the records themselves, as:

- the seizure of Zaręba’s earnings along with the imposition of a penalty has been admitted,

- it has also been admitted that Zaręba was forced to work two consecutive shifts,

- the claim that there was no money in the cashier’s office does not in any way justify the withholding of payment,

- and finally, the circumstances cited do not justify forcing Zaręba to complete two shychtas (shifts) directly one after the other.

It is noted here that the final paragraph of the protocol—where Zaręba testified that in Fuchs’ mine, it often happens that workers are made to work continuously for 24 hours—was omitted from the copy provided to Fuchs. This omission was deliberate, as the intention was to question the workers listed in the protocol during an upcoming visit to Boryslav, without giving Fuchs or Meller, who had already been warned about this matter, the opportunity to influence the workers and pressure them into giving false testimony.

It is further noted that the complainant, Jan Zaręba, according to reports from other Boryslav workers, is regarded as a relatively intelligent man, conscious of his human dignity and determined to free himself, by any means, from the exploitation by the mine’s cashier and his overseers…

Comment is caming