After declaring independence in 1991, Ukraine inherited from the Soviet Union a centralized economy almost entirely dominated by state ownership. Industry, agriculture, services, and housing were all controlled by the state. The transition to a market economy therefore required large-scale privatization—the transfer of state property into private hands. Although the first steps toward privatization had already begun before the dissolution of the USSR, the foundational law “On Privatization of State Property”—which still defines the principles of privatization today—was adopted in March 1992.

Almost simultaneously, the Verkhovna Rada adopted the Law “On Privatization Certificates,” which introduced a certificate (voucher) model: each citizen received a privatization certificate that could be used to acquire a share in an enterprise. In the following years, an annual State Privatization Program was approved, setting out the objectives, objects, and mechanisms of privatization. To implement these policies, the State Property Fund of Ukraine was established in 1994 as the central executive body responsible for carrying out privatization.

The first stage of privatization focused on the sale of small properties—shops, cafés, and service enterprises. This process was often described as “privatization by labor collectives,” since employees were granted the primary right to purchase their workplace assets. Because most of the population lacked savings, privatization was carried out through vouchers: citizens received certificates that could be exchanged for shares. On this basis, thousands of large enterprises were transformed into joint-stock companies. In practice, however, many people quickly sold their vouchers at minimal prices to financial intermediaries or “privatization funds,” which in turn consolidated control over enterprises. What followed was a massive redistribution of state property into private hands, with enterprise directors frequently emerging as the new owners—though many had little interest in investing in or modernizing production.

Beginning in October 1994, President Leonid Kuchma introduced a policy intended to curb the chaotic course of early privatization by strengthening the government’s role as regulator. In practice, however, this shift facilitated the rise of the oligarchy: access to the privatization of large enterprises was effectively restricted to groups loyal to, or closely connected with, the authorities. This primarily concerned strategic assets—power companies, metallurgical plants, and mines. Such enterprises were frequently sold at below-market prices, through non-transparent procedures that excluded genuine competition.

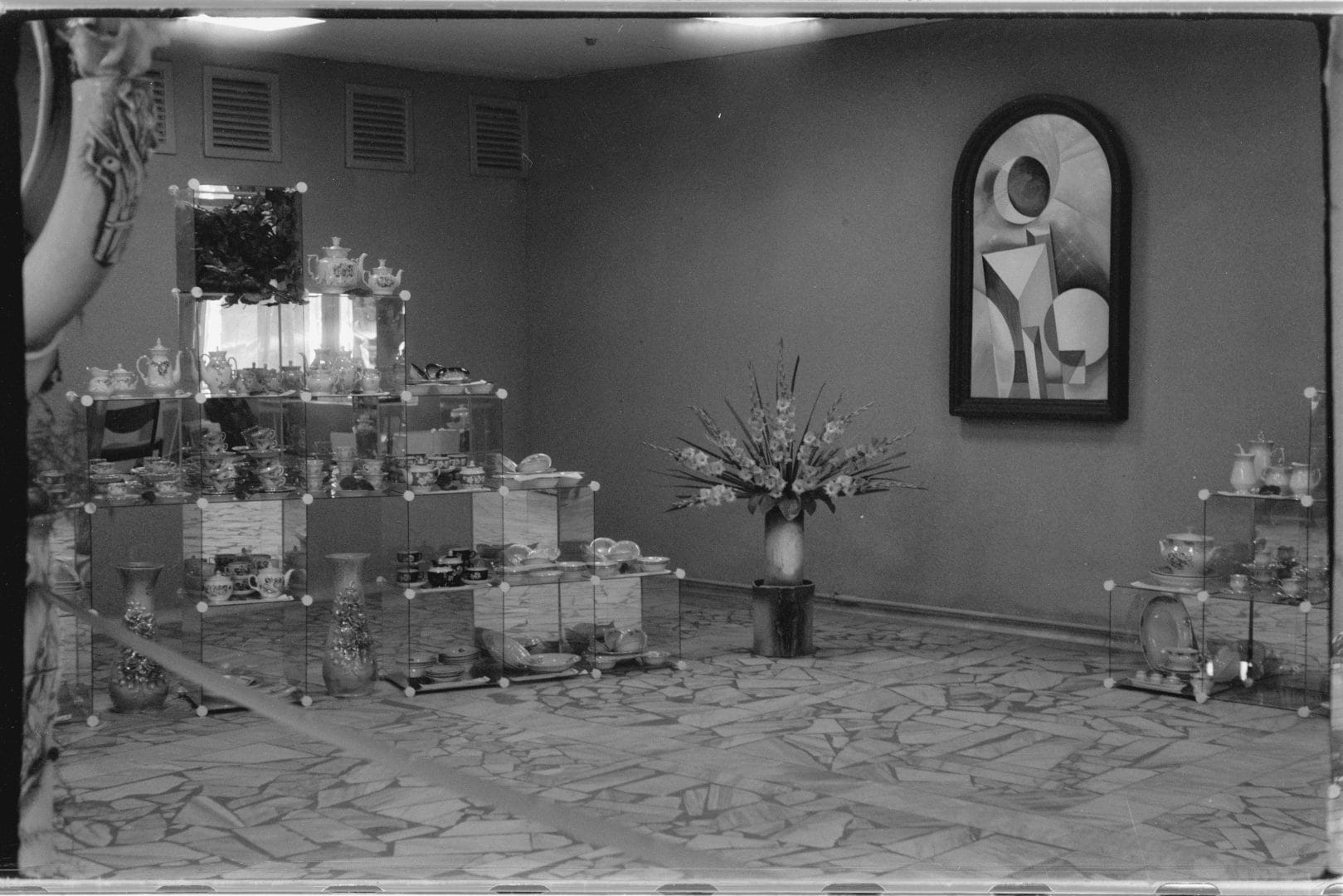

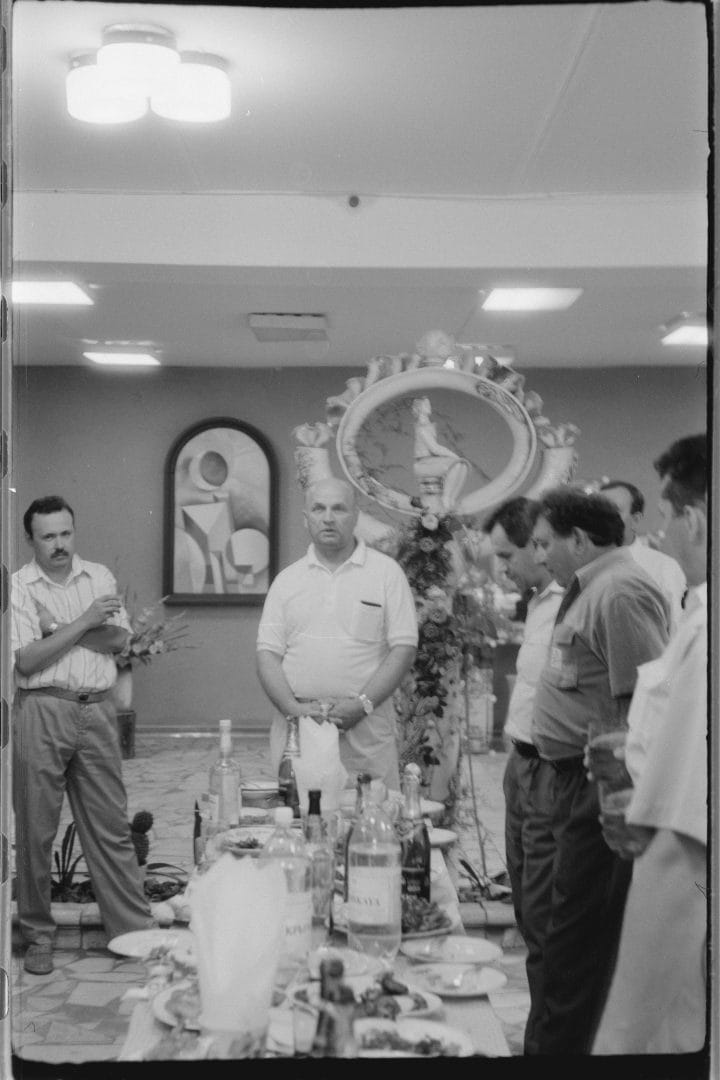

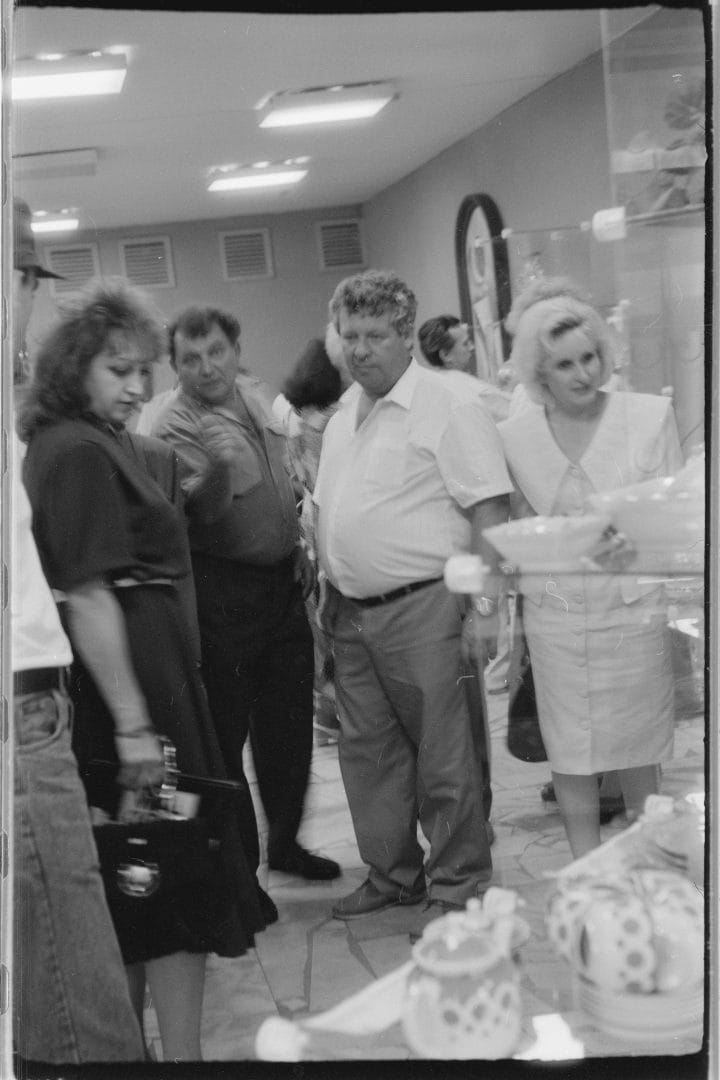

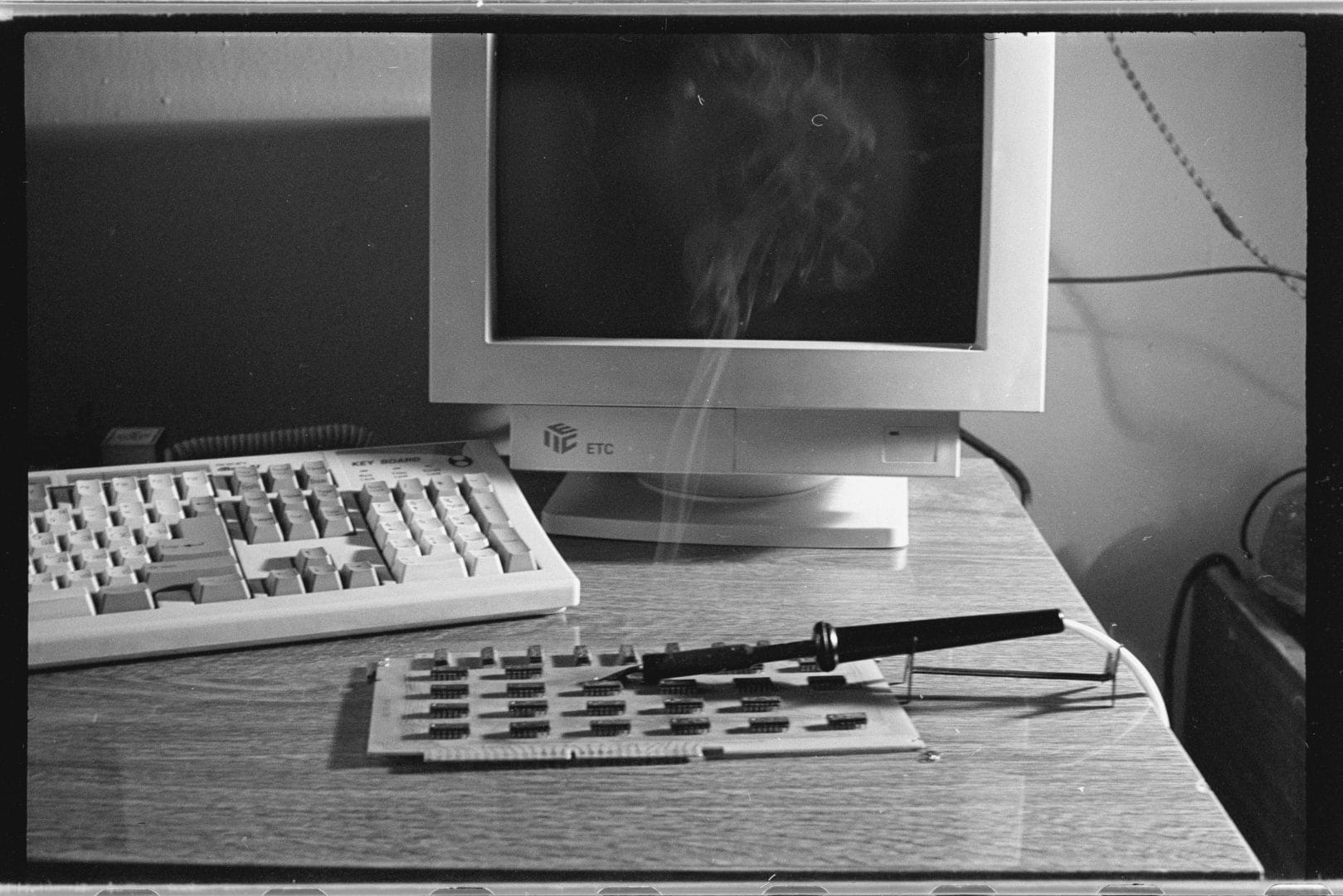

The photographs below, preserved in the archives of the Druzhkivka newspaper Okno (Donetsk oblast, Ukraine), illustrate the early stage of privatization and the subsequent crisis that unfolded at two local enterprises: the Druzhkivka Porcelain Factory and the Remschetmash computer repair and maintenance plant. The first series of images documents the opening of a retail store selling porcelain produced by the Druzhkivka factory. Built in 1971, the factory was privatized in 1993 and reorganized as the collective enterprise Ranok, a commercial and industrial firm.

The photographs, taken on July 26, 1995, capture the ceremonial launch of the factory store.

The photographs presented here from the archives of the newspaper Okno [literally “window” — tr.note] document the creative work of its editorial staff, who sought to critically reflect on the realities of Ukraine’s economic transformation in the 1990s through artistic and allegorical means. Founded in 1994 by local entrepreneurs, the newspaper positioned itself in opposition to the old communist nomenclature, which still retained control over local government bodies and capitalized on the widespread disappointment and confusion following the collapse of the Soviet Union. The founders of Okno were the insurance company ASKO-Donbas Pivnichny (established in 1991) and its affiliated printing company PrimaPress. The emergence of the paper ended the local authorities’ monopoly over the information space, creating a platform for criticism of both the authorities and the Soviet past. With its emphasis on business, culture, and history, Okno was quickly labeled “petty bourgeois” by its opponents.