“It had never crossed my mind that I would become Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Council. Traditionally, this position was reserved for a senior party worker—usually the secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, or at the very least, a leader holding a position no lower than first secretary of a oblast party committee, and typically a member of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine. So, when Oleksii Feodosiyovych Vatchenko passed away at the end of 1984, I, then serving as Deputy Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR, never expected to be appointed to this post. It truly never occurred to me—and I say this with complete sincerity.

The flowers on O. Vatchenko’s grave had not yet wilted when the likely candidate from the Ordzhonikidze building (now Bankova Street) was already hurrying to inspect what he assumed would be his future official residence. He dispatched his assistant to the Supreme Soviet to examine the offices and assess the situation, and sent a driver to find out what kind of vehicles were available in the motor pool for the head of the Presidium—what he would be driving. He was even inquiring about salaries and benefits.

At that time, we were preparing for the winter session of the Presidium, which was to consider the draft plan for Ukraine’s socio-economic development for 1985, along with the draft budget. The workload was enormous. Preparatory groups from all Presidium committees were in session, and the Planning and Budget Committee was reviewing the draft documents in full.

I attended all the meetings, carefully listening to the comments and suggestions of the deputies. In the past, O. Vatchenko had reported on the results of considering such issues to the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine. Now it was my turn to do so. Before the Politburo meeting, I requested an appointment with V. Shcherbytskyi and proposed that the election of the Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Council be included on the agenda for the upcoming session.

‘Let’s not rush,’ replied Volodymyr Vasyliovych. ‘You, Valentyna Semenivna, had to work independently when Oleksii Feodosiyovych was ill, and you coped well with the responsibilities. Let’s hold off on this matter for now.’ ‘Well, we’ll wait, we’ll wait,’ I told myself. ‘Although it hasn’t been easy—there’s the additional workload in the Presidium, and now duties in the Politburo as well. Still, I’ll somehow manage until the winter session.’

The winter session proved successful, earning high marks from both the Politburo and Volodymyr Vasyliovych himself. Next came the review of budget proposals and socio-economic development plans for the oblasts, cities, and districts. I travelled extensively, attending sessions at the oblast, city, and district levels.

Days went by, filled with routine, everyday tasks. No one raised the question of electing a Chairman of the Presidium, and no one spoke to me about it. However, V. V. Shcherbytskyi began attending the Presidium meetings of the Supreme Council more frequently and invited me to the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine with various pieces of information. Looking back now, I can see that he was clearly testing me again, observing me more closely. At the time, I had no idea what was going on. Meanwhile, the secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine—who was preparing to take the position of Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of Ukraine—began showing increased interest in the work of the Presidium, the committees of the Supreme Council, the reception of citizens, the consideration of pardon cases, and so forth.

It was 1985. In early March, Volodymyr Vasyliovych led the delegation of the Supreme Council of the USSR to the United States. The trip was extremely demanding. While the Soviet delegation was in the United States, on 11 March, General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union K. U. Chernenko passed away.

An emergency meeting of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was convened in Moscow, at which M. S. Gorbachev was elected General Secretary. V. Shcherbytskyi was urgently recalled from his trip.

12 March 1985 – A call from Moscow. It was Volodymyr Vasyliovych. He congratulated me on my anniversary and on receiving a high state award—the Order of the October Revolution—and said:

‘Today, Valentyna Semenivna, celebrate your anniversary. Tomorrow, you must be in Moscow, at the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.’

‘What happened, Volodymyr Vasyliovych?’

‘Nothing special. I have spoken with M. S. Gorbachev about recommending you for the position of Chair of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of Ukraine. The Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union wants to get to know you better.’

‘Volodymyr Vasyliovych! I beg you not to do this. I am not ready for such a position. If you still trust me, I will continue working where I am now. Moreover, I do not want any complications with the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine. You probably know who among them already sees himself in this role.’

‘Valentyna Semenivna! You have been ready for this position for a long time. Do you think we in the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine don’t know how the Presidium operates? Besides, we cannot turn the Presidium into a nest for pensioners. Talking to members of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine is my concern. Tomorrow, I repeat, you must be at the Central Committee. The matter is settled. Goodbye.’

And he hung up.

I hung up the phone, not knowing what to do. I felt confused and overwhelmed. Perhaps someone else in my place would have been delighted, but I was not happy. It wasn’t fear—no!—but rather the clear understanding of the immense responsibility that would fall on my shoulders and of how many new problems would arise.

Just then, the head of the Secretariat of the Presidium of the Supreme Council came in and said: ‘Valentyna Semenivna, we’re getting calls from ministries, departments, oblast executive committees… They’re asking when they can congratulate you on your anniversary.”

‘What anniversary! The country is in mourning. I have to be in Moscow tomorrow,’ I replied irritably.

Instead of celebrating my anniversary, I began preparing for the trip to Moscow. The train departed that evening. Upon arrival, I was warmly received at the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and invited to meet with Mikhail Gorbachev, General Secretary of the Central Committee of the CPSU. Mikhail Sergeyevich recalled our first meeting at the 14th Congress of the All-Union Leninist Young Communist League. At that time, as the former secretary of the Stavropol Regional Committee of the Komsomol and a member of the Central Committee of the All-Union Leninist Young Communist League, he had been invited to attend the congress. I, the ‘newly elected’ secretary of the Central Committee of the Komsomol of Ukraine, was there as a delegate.

Mikhail Sergeyevich spoke of his Ukrainian roots—his mother was Ukrainian, and Raisa Maksymivna’s father was also Ukrainian. He talked about Ukraine, its role within the USSR, and stressed the tasks facing the Supreme Council of Ukraine in implementing the decisions of the party congress and strengthening the role of the People’s Deputies’ Councils in carrying out socio-economic development plans. He assured me that I had nothing to fear in taking on such a large and responsible position, reminding me of my broad experience in schools, the Komsomol, public organisations, and government institutions. He noted that in my ten years as First Deputy Chair of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR, I had gained substantial experience in law-making, overseeing the activities of state and local authorities in implementing session decisions and complying with legislation. My work in cooperation and communication with people, he added, had also been of great value. He expressed his confidence that the experience I had accumulated would help me meet the complex challenges of state-level work.

At the same time in Kyiv, V. Shcherbytskyi informed the members of the Politburo of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine: ‘Valentyna Semenivna is in Moscow, meeting with Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev. At the next session of the Supreme Council of Ukraine, we will recommend her for the post of Chair of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of the Ukrainian SSR. I hope the session will support us.’

As I was later told, once Shcherbytskyi finished speaking, the room fell silent—just like in Hohol’s The Inspector General. It was clear that some members of the Politburo had not been expecting such an announcement.

Of course, a precedent had been set—the Chair of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR was now a woman! The second-highest position in the state.

The session supported the proposal of the Politburo. The deputies spoke kindly of me, for which I was deeply grateful.

But my mind was already racing ahead, thinking about how best to organise the work of the Supreme Council, the Presidium, and the standing committees so that the results of the highest state authority would be felt at the local level—from the oblast, city, and district to every work collective, family, and individual.”

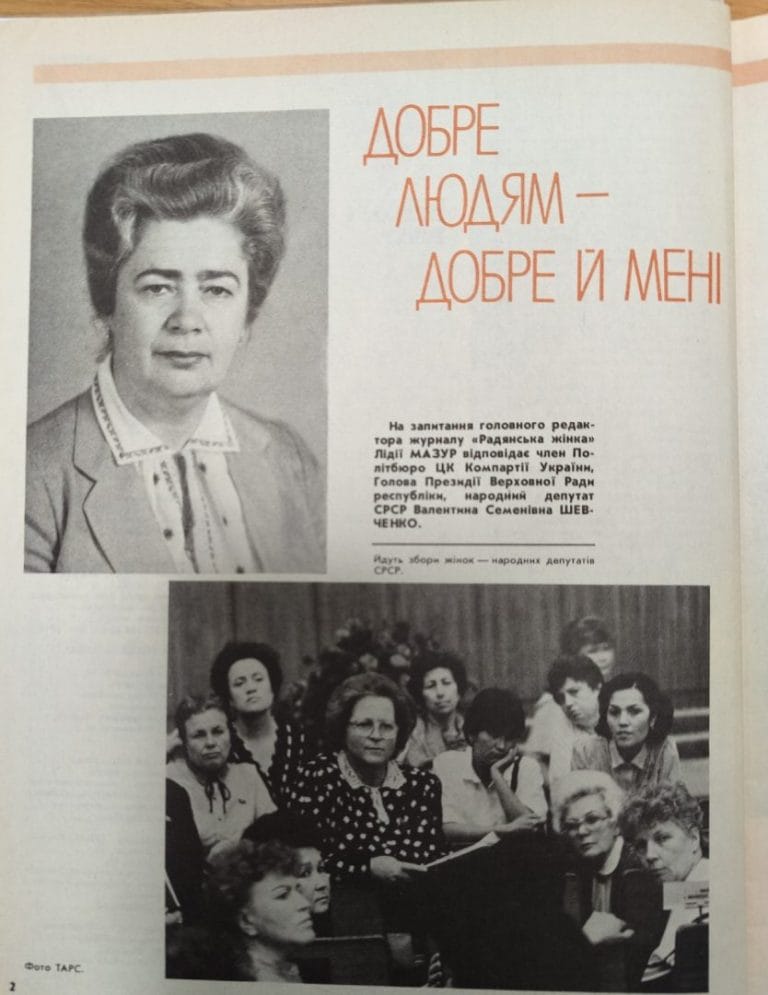

Valentyna Shevchenko (1935–2020) worked as a senior pioneer leader and a secondary school teacher, later holding leadership positions in the Komsomol and party bodies of the Ukrainian SSR. She served as Deputy Minister of Education and as head of the Society for Friendship and Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries. During the Perestroika period, she rose to the position of Chairwoman of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of the Ukrainian SSR. In independent Ukraine, Valentyna Shevchenko led several civic organizations engaged in humanitarian issues.

Her memoirs cover the period from her childhood to the first decade of Ukrainian independence, becoming more detailed as they approach the present. She explained that her motivation for writing them was the interest of young people in Soviet history, about which, as she claimed, “no one has told them the truth and still does not—neither teachers nor the bourgeois mass media.” “In newspapers, on television, and on the radio,” she wrote, “our past is painted in dark colors” (Shevchenko, 2005: 10).

In her memoirs, the author does not explicitly address the issue of women’s underrepresentation in leadership positions in Soviet Ukraine. She draws attention to her gender only twice, both times during her career advancements. The first instance is her appointment in 1960 to a high party post: “I, a 25-year-old woman, was recommended as secretary of the district party committee” (Shevchenko, 2005: 49). The second mention refers to 1985, when she became head of the Presidium of the Supreme Council of the Ukrainian SSR. A fragment of her recollections of this event is provided below.