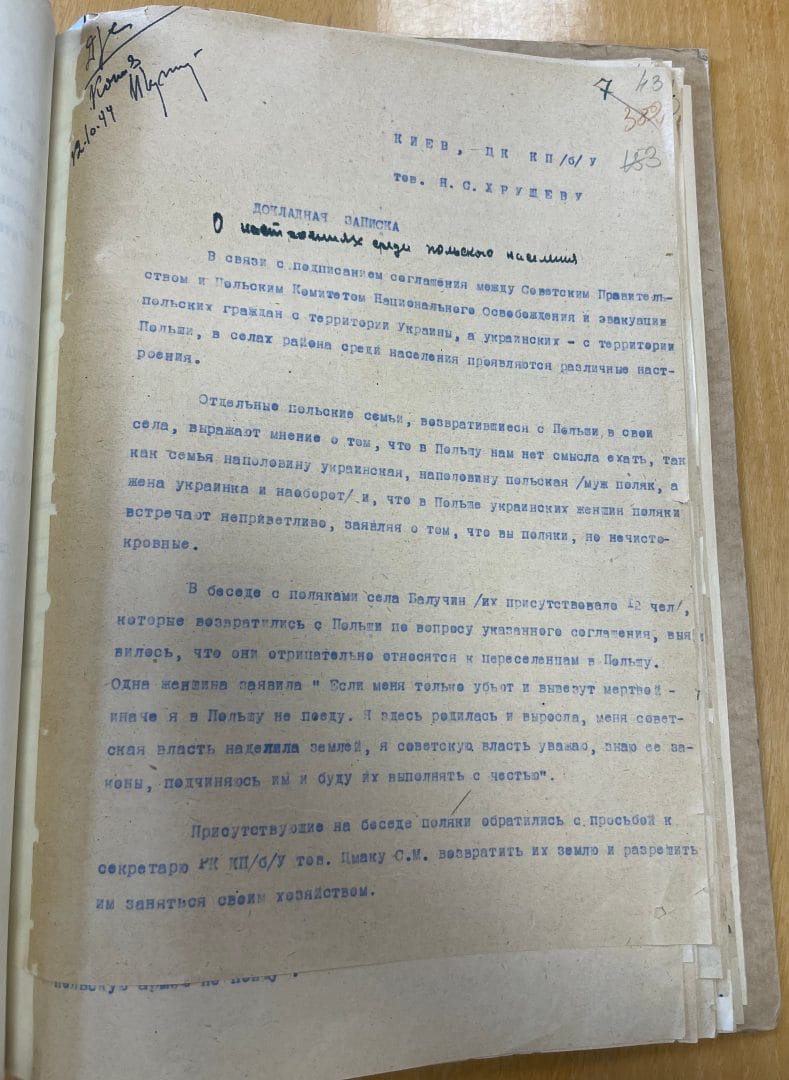

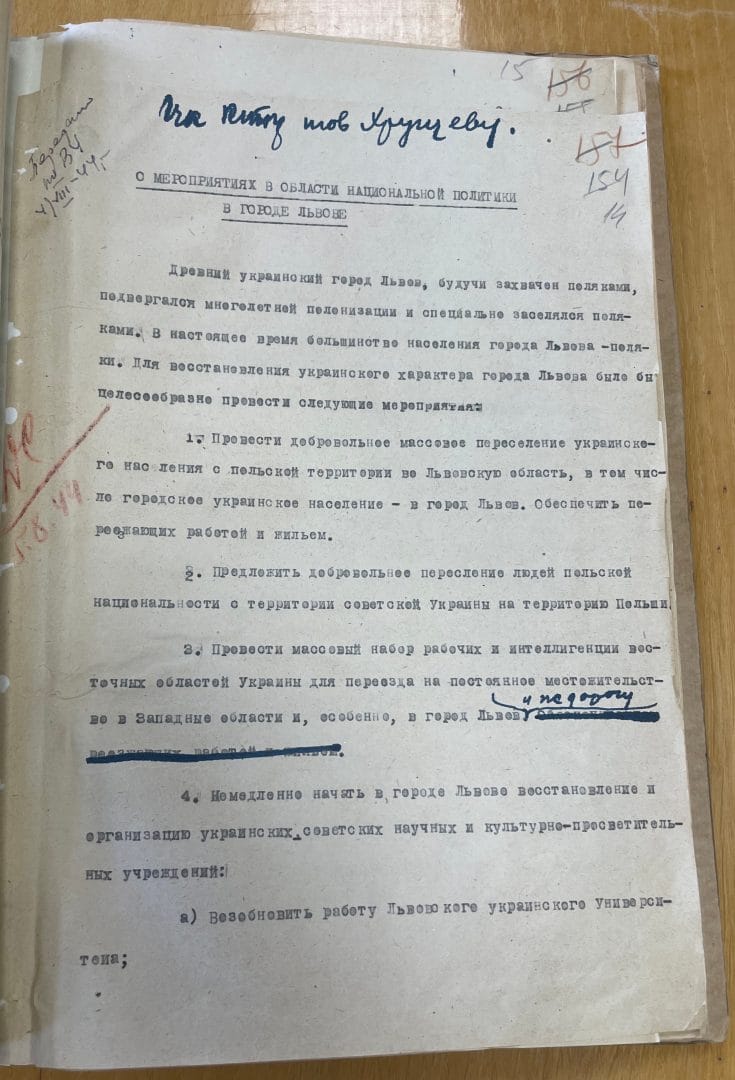

Kiev, Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine

Comrade N.S. Khrushchev

Memo

On the mood among the Polish population (handwritten)

In connection with the signing of an agreement between the Soviet Government and the Polish Committee for National Liberation regarding the evacuation of Polish citizens from the territory of Ukraine and Ukrainian citizens from the territory of Poland, various sentiments are emerging among the rural population in the district’s villages.

Some Polish families who have returned from Poland to their villages express the view that there is no point in moving to Poland, as their families are mixed / half Ukrainian and half Polish (the husband is Polish and the wife is Ukrainian, or vice versa) / and they add that in Poland, Polish people treat Ukrainian women with hostility, saying that although they are Polish, they are not of “pure blood.”

In a conversation / with 12 Poles / from the village of Baluchin who had returned from Poland, regarding the aforementioned agreement, it became clear that they held a negative attitude toward resettlement in Poland. One woman stated: “They will have to kill me and take me away dead—otherwise I will not go to Poland. I was born and raised here, the Soviet authorities gave me land, I respect the Soviet authorities, I know their laws, I obey them, and I will honor them.”

The Poles present at the meeting asked the secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine, Comrade Pmak S.M., to return their land and allow them to engage in farming.

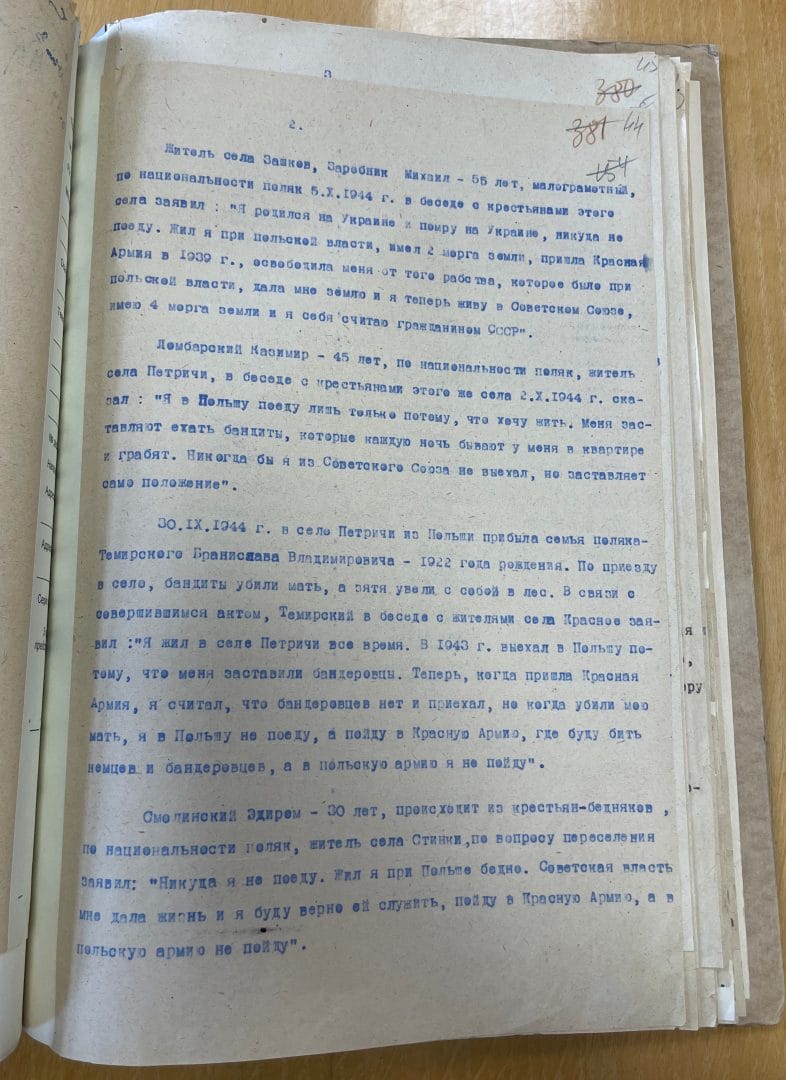

A resident of the village of Zashkov, Zarobnik Mikhail, 55 years old, illiterate, Polish by nationality, on May 5, 1944, said in a conversation with fellow villagers: “I was born in Ukraine, and I will die in Ukraine—I’m not going anywhere. I lived under Polish rule and had two morgens of land. Then the Red Army came in 1939, gave me land, and now I live in the Soviet Union, have four morgens, and consider myself a citizen of the USSR.”

Lombardsky Kazimir, 45 years old, Polish by nationality, a resident of the village of Petrichi, said in a conversation with fellow villagers on February 2, 1944: “I will go to Poland only because I want to live. I’m being forced out by bandits who come to my apartment every night and rob me. I would never have left the Soviet Union, but the situation itself is forcing me to do so.”

On September 30, 1944, a Polish family arrived in the village of Petrichi from Poland. Among them was Bronislav Vladimirovich Temirsky, born in 1922. Upon their arrival, bandits killed his mother and took his son-in-law into the forest. In connection with this incident, Temirsky said in a conversation with residents of the village of Krasnoye: “I lived in the village of Petrichi the whole time. In 1943, I left for Poland because I was forced to by the Banderites. Now that the Red Army has returned, I thought the Bandera followers were gone, so I came back. But when they killed my mother, I decided not to go back to Poland, but to join the Red Army and fight both the Germans and the Bandera followers. I will not join the Polish army.”

On the other hand, some Ukrainians have made anti-Soviet statements, such as:

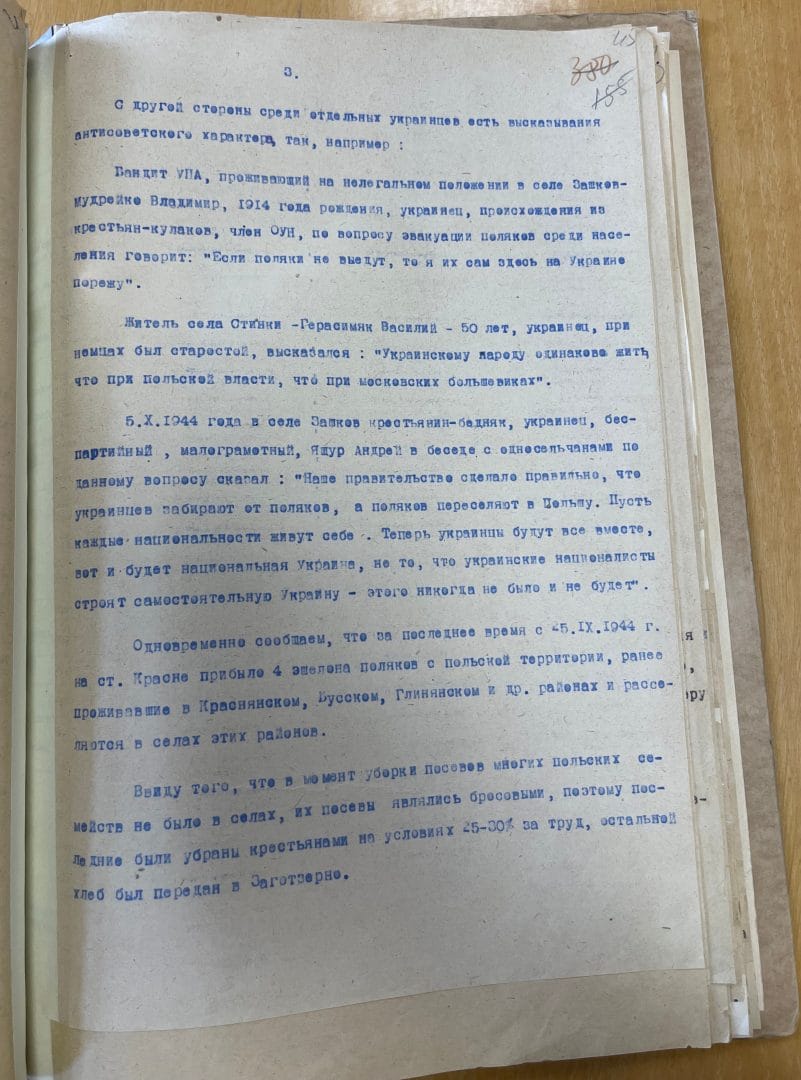

An UPA bandit living illegally in the village of Zashkov, Vladimir Mudreyko, born in 1914, Ukrainian, of peasant-kulak origin and a member of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (OUN), said regarding the evacuation of Poles: “If the Poles don’t leave, I’ll cut them up myself here in Ukraine.”

A resident of the village of Stinki, Vasily Gerasimyak, 50 years old, Ukrainian, who served as village head under the Germans, said: “For the Ukrainian people, living under Polish rule is the same as living under the Moscow Bolsheviks.”

On October 5, 1944, in the village of Zashkov, a poor Ukrainian peasant, non-party member, and illiterate, Andrey Yashchur, said in a conversation with fellow villagers on this issue: “Our government did the right thing by taking Ukrainians away from the Poles and resettling the Poles in Poland. Let each nationality live its own life. Now Ukrainians will all be together, and there will be a national Ukraine—not the kind of independent Ukraine the Ukrainian nationalists are building. That has never existed and never will.”

At the same time, we would like to inform you that since September 25, 1944, four trains carrying Poles from Polish territory have arrived at the Krasnoye station. These individuals had previously lived in the Krasnyansky, Bussky, and Glinyansky districts and are now being resettled in villages within those same districts.

Because many Polish families were absent from their villages during the harvest season, their crops were left unattended and were therefore harvested by local peasants under labor terms of 25–301, with the remaining grain transferred to Zagotzerno.

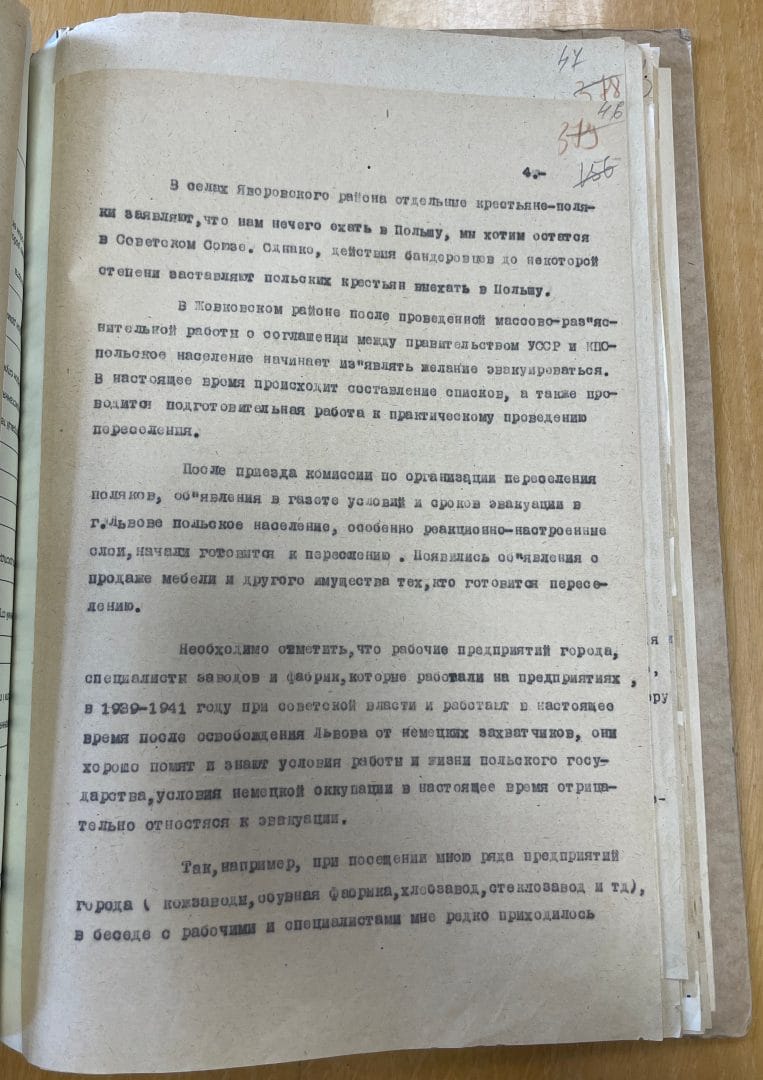

In all matters concerning the Yavorov district, individual Polish peasants state that they see no reason to go to Poland and wish to remain in the Soviet Union. However, the actions of the Banderites do, to some extent, compel Polish peasants to consider leaving for Poland.

In the Zhovkovsky district, following a large-scale information campaign about the agreement between the Soviet government and the KPS, the Polish population has begun to express a desire to evacuate. Lists are currently being compiled, and preparatory work is underway for the practical implementation of the resettlement.

It should be noted that workers from the city’s enterprises—specialists from factories and plants who were employed under Soviet rule in 1939–1941 and who are currently working after the liberation of Lvov from the German occupiers—remember well and are fully aware of the working and living conditions under the Polish state and during the German occupation. As a result, they now have a negative attitude toward evacuation.

For example, during my visits to a number of city enterprises (leather factories, a shoe factory, a bread factory, a glass factory, etc.), in conversations with workers and specialists, I rarely encountered anyone who expressed a desire to go to Poland.

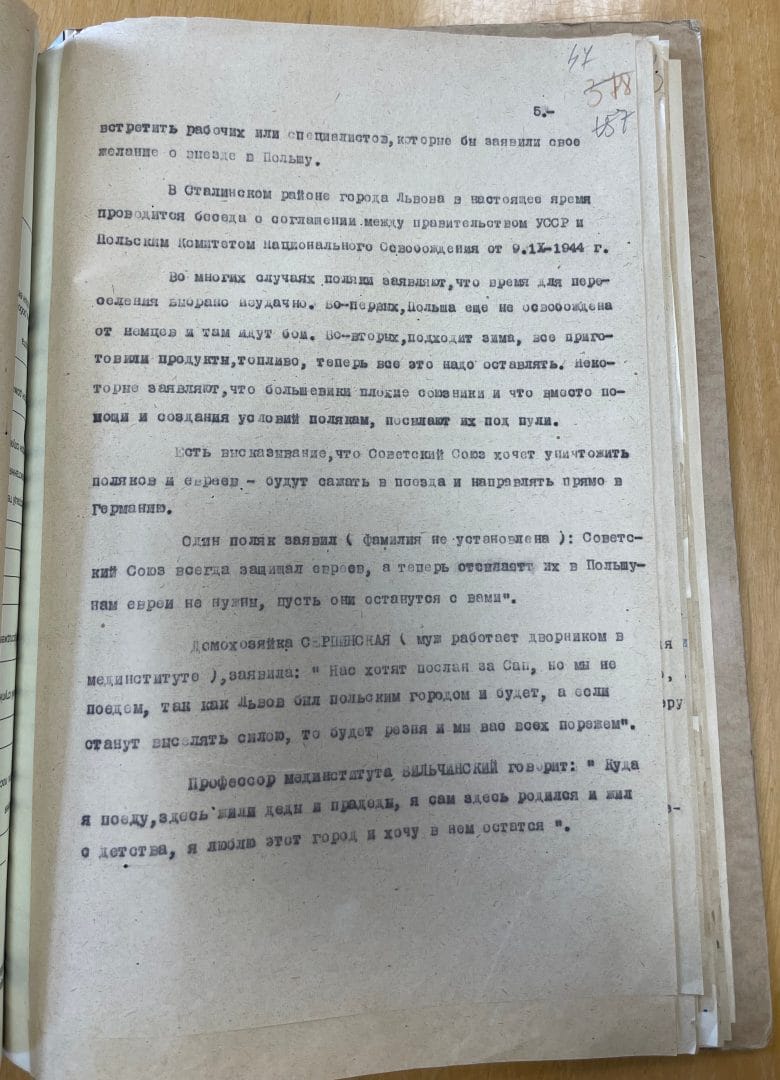

In the Stalin district of Lvov, discussions are currently underway regarding the agreement between the government of the Ukrainian SSR and the Polish Committee of National Liberation dated September 9, 1944.

In many cases, Poles argue that the timing of the resettlement is unfortunate. First, Poland has not yet been fully liberated from the Germans, and fighting is still ongoing there. Second, winter is coming; people have prepared food and fuel, and now they are being forced to leave everything behind. Some claim that the Bolsheviks are poor allies who, instead of supporting the Poles and creating favorable conditions, are sending them to their deaths.

There are also rumors that the Soviet Union intends to destroy the Poles and Jews—that they will be loaded onto trains and sent directly to Germany.

One Pole (name unknown) stated: “The Soviet Union has always protected Jews, and now it is sending them back to Poland—we don’t need Jews; let them stay with you.”

Housewife SERPINSKAYA (whose husband works as a janitor at a medical institute), said: “They want to send us beyond the San River, but we won’t go, because Lvov was a Polish city and will remain so. If they try to evict us by force, there will be a massacre, and we will cut you all down.”

Professor VILCHINSKY of the medical institute said: “Where would I go? My grandfathers and great-grandfathers lived here, I was born here and have lived here all my life. I love this city and want to stay.”

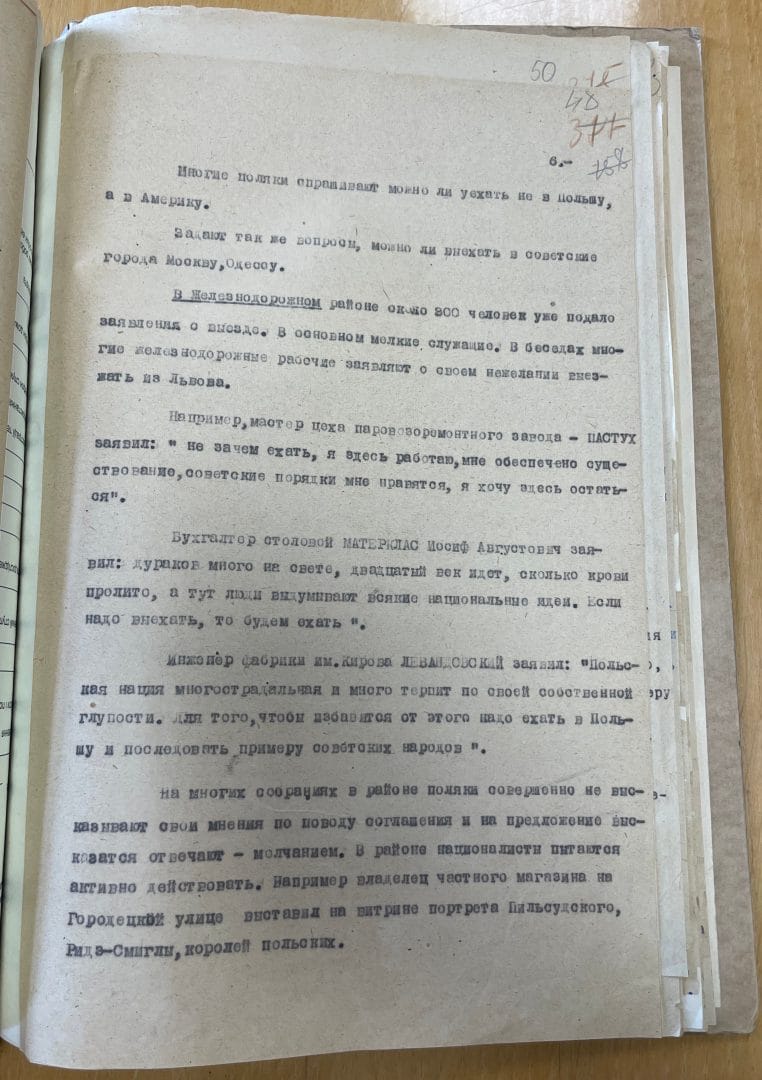

Many Poles are asking whether they can leave not for Poland, but for America.

They are also inquiring if they might relocate to Soviet cities such as Moscow or Odessa.

In the Zheleznodorozhny district, about 300 people have already applied to leave, most of whom are low-level employees. In conversations, many railway workers express that they do not want to leave Lvov.

For example, a master craftsman at the locomotive repair plant PASTUKH said: “There’s no point in leaving. I work here, I have a secure livelihood, I like the Soviet system, and I want to stay.”

Joseph Avgustovich MATERKLAS, the accountant at the canteen, said: “There are many fools in the world. It’s the 20th century, so much blood has been shed, and yet people still come up with all sorts of nationalist ideas. If we have to leave, then we’ll leave.”

LEVANDOVSKY, an engineer at the Kirov Factory, said: “The Polish nation is long-suffering and endures much because of its own foolishness. To overcome this, they need to go to Poland and follow the example of the Soviet peoples.”

At many meetings in the district, Poles choose not to express their opinions about the agreement and respond to requests to speak with silence. Meanwhile, nationalists are attempting to be active in the district. For example, the owner of a private shop on Gorodetskaya Street has displayed portraits of Piłsudski, Rydz-Śmigły, and Polish kings in his shop window.

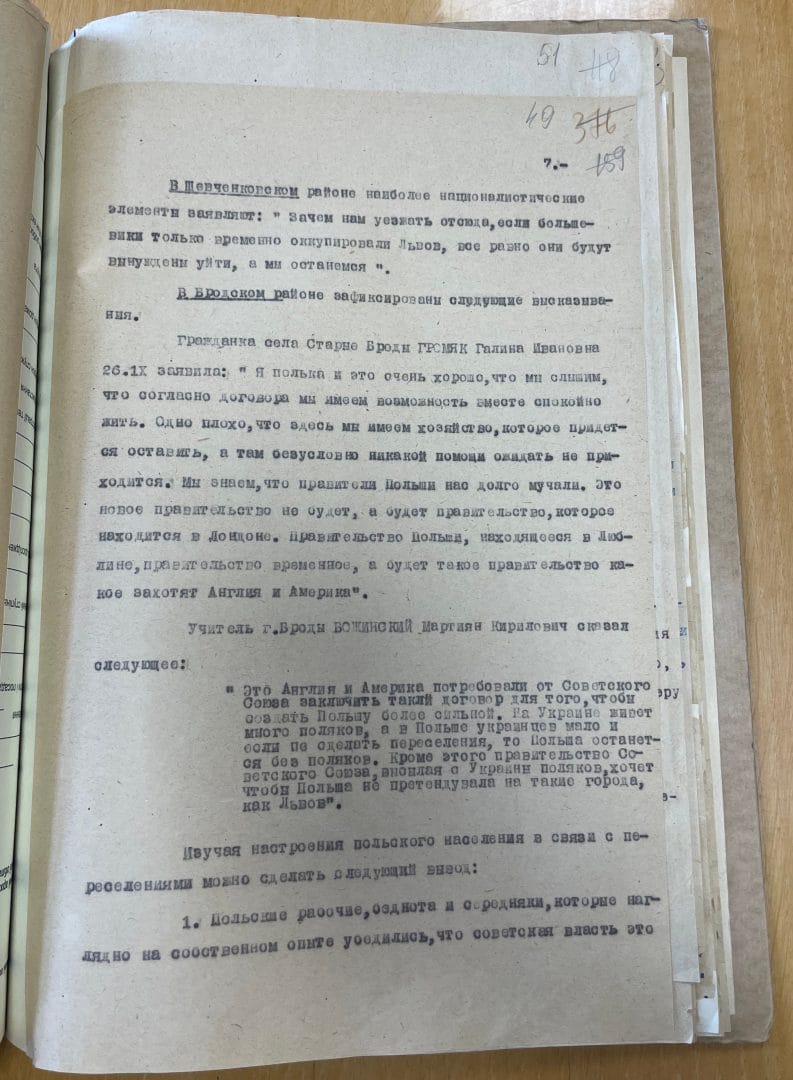

In the Shevchenko district, the most nationalistic elements declare: “Why should we leave if the Bolsheviks have only temporarily occupied Lvov? They will be forced to leave eventually, and we will remain.”

In the Brodsky district, the following statements were recorded.

Galina Ivanovna GROMYAK, a resident of the village of Starye Brody, stated on September 26: “I am Polish, and it is very good that, according to the agreement, we can live together in peace. The only downside is that we have a farm here which we will have to leave, and we certainly cannot expect any help there. We know the Polish rulers have tormented us for a long time. This new government will not last; there will be a government based in London. The Polish government in Lublin is temporary; eventually, there will be a government supported by England and America.”

Teacher Martian BOZHINSKY from Brody said: “It was England and America that insisted the Soviet Union sign this agreement to create a stronger Poland. Many Poles live in Ukraine, but few Ukrainians live in Poland, and if no resettlement occurs, Poland will be left without Poles. Moreover, by expelling Poles from Ukraine, the Soviet government aims to prevent Poland from laying claim to cities such as Lvov.”

Studying the mood of the Polish population in connection with the resettlements, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- Polish workers, the poor, and the middle class—who have seen for themselves that Soviet power is their power, providing them with work and establishing normal cultural conditions for life—mostly express a desire to remain in the Soviet Union.

- A portion of the reactionary Polish population, influenced by the Polish émigré government in London, is attempting to use the resettlement process to stir nationalist feelings among other Poles, to foster dissatisfaction with Soviet authority, and to claim that Soviet power in Lvov and the western regions of Ukraine will not endure, urging Poles not to resettle beyond the San River.

Secretary of the Lvov Oblast Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine

(I. Grushetsky)

October 14, 1944

This report, prepared by the head of the Lviv oblast party committee, and addressed to Nikita Khrushchev on 14 October 1944, offers an official assessment of Polish attitudes in the region one month after the signing of the Polish-Soviet population exchange agreement. Presented as a “report on moods,” it contains a series of quoted remarks attributed to local inhabitants. These very manifold moods highlight the complexity of the population transfer on the ground. Far from a smooth or unanimous process, the implementation of resettlement encountered hesitation, fear, ambivalence, and selective compliance. While the report depicts some readiness to leave, it also underscores that departures were often driven less by ideological conviction than by pragmatic considerations, security, survival, or the hope of better opportunities. In this sense, the document indirectly reveals some of the difficulties Soviet authorities faced in carrying out the resettlement policy. We can learn more about the language and terminology used in the report: the population transfer is described in official terms such as “evacuation” and others, revealing how Soviet authorities framed the operation in neutral or administrative language.

Although it presents itself as a collection of cited testimonies, the report must be approached critically. We do not know how, when, or under what circumstances these remarks were collected, nor whether the cited individuals have actually existed. As with many party files, the content is shaped by the institutional logic of reporting upward: the report documents not simply the “moods” of the population, but what could be written, what was deemed politically relevant, and what narratives would resonate with the leadership in Kyiv and Moscow. In this sense, it tells us less about the actual distribution of opinion among Poles in Lviv and more about the categories through which Soviet officials sought to perceive and manage the situation

Following Ann Laura Stoler’s insights on colonial archives, it should be read not as a transparent window into past realities but as an artifact of the bureaucratic and ideological conditions that shaped what could be recorded, repeated, and transmitted [1]. Its value, therefore, lies not only in the voices it claims to capture but also in the ways it reveals the practices of Soviet rule and the selective construction of local reality in postwar Lviv.

[1] Ann Laura Stoler, ‘Colonial Archives and the Arts of Governance: On the Content in the Form’, in Archives, Documentation, and Institutions of Social Memory: Essays from the Sawyer Seminar, ed. Francis X. Blouin, University of Michigan Press, 2010.