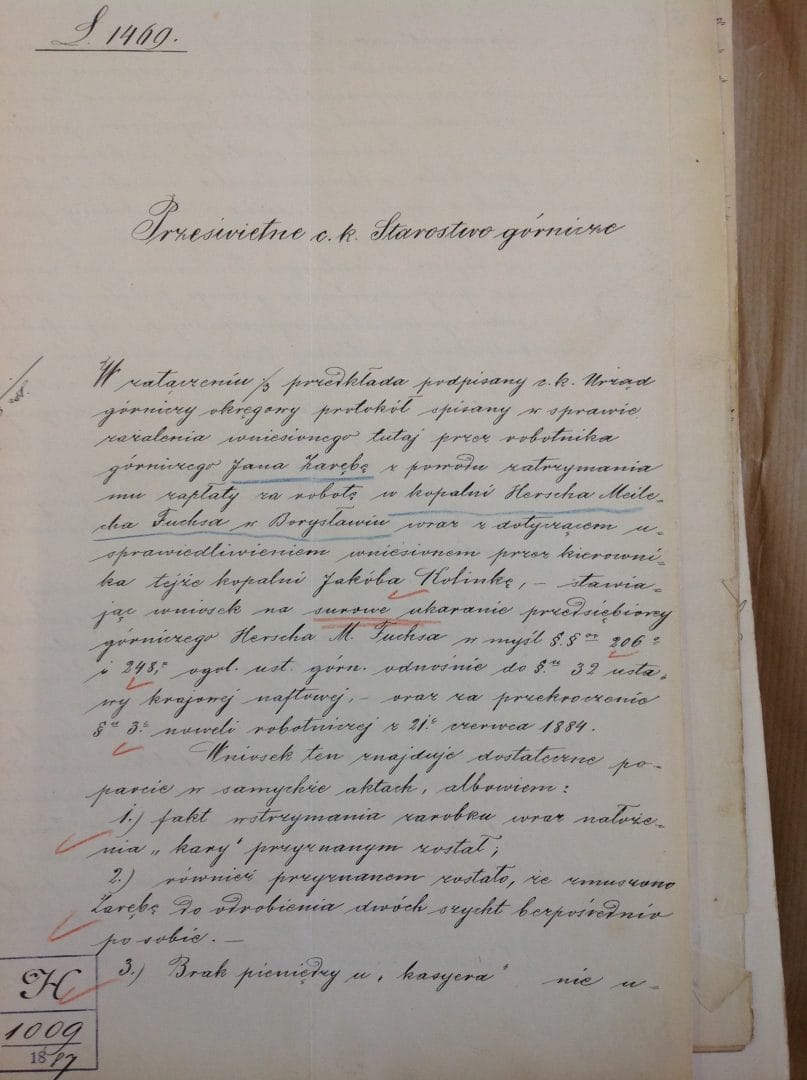

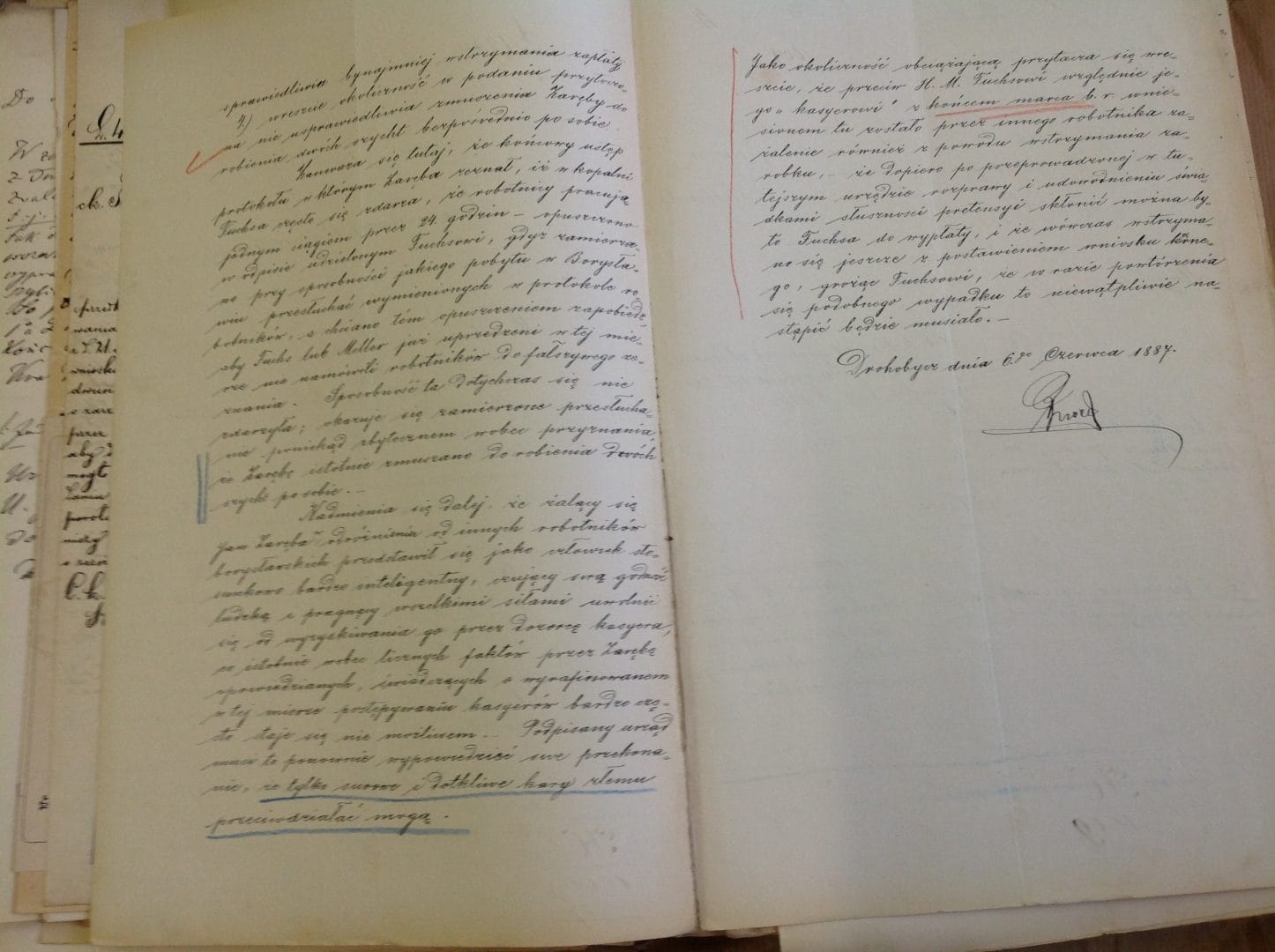

The protocol of the district mining administration to the Krakow starostwo, dating from 1887, investigates a complaint by minerJan Zaręba against entrepreneur Hersch Mielech Fuchs regarding unpaid wages. The mining administration conducted a detailed inquiry at the enterprise to determine whether this case reflected systematic violations of workers’ rights. The administration sided with the miner and even provided the entrepreneur with a separate protocol in which Zaręba outlined these violations. This allowed the administration to conduct a survey among other mine workers, who were often too afraid to speak out due to the threat of dismissal. In this case, the entrepreneur was Jewish and the worker Polish. Another figure indirectly mentioned is the “cashier”—that is, the mine supervisor—a position also commonly held by Jews. Testimonies from inspectors and other observers of Boryslav at the end of the 19th century frequently criticize entrepreneurs and cashiers for failing to comply with labour laws, neglecting mutual aid funds, and exploiting workers. Such criticism often employed anti-Semitic language, since cashiers and entrepreneurs were predominantly Jewish. This protocol demonstrates that workers were aware of and made use of mechanisms to protect their rights, and that the administration provided them with opportunities to challenge the owners.

District Mining Office to the Cracow Mining Department, 1887 (National Archives in Krakow, collection 207, file 197)

(translation from Polish by Vladyslava Moskalets)

This protocol concerns the complaint filed by mining worker Jan Zaręba regarding the withholding of his wages for work at the Hersch Mielech Fuchs mine in Boryslav. Alongside this is the response submitted by the mine’s manager, Jakob Kolinka. The protocol puts forward a request for the severe punishment of the mining entrepreneur Hersch M. Fuchs, in accordance with Paragraphs 206 and 248 of the General Mining Law, and with reference to Paragraph 32 of the National Petroleum Law, as well as for violations of Paragraph 3 of the Workers’ Amendment of June 21, 1884.

This conclusion is sufficiently supported by the records themselves, as:

- the seizure of Zaręba’s earnings along with the imposition of a penalty has been admitted,

- it has also been admitted that Zaręba was forced to work two consecutive shifts,

- the claim that there was no money in the cashier’s office does not in any way justify the withholding of payment,

- and finally, the circumstances cited do not justify forcing Zaręba to complete two shychtas (shifts) directly one after the other.

It is noted here that the final paragraph of the protocol—where Zaręba testified that in Fuchs’ mine, it often happens that workers are made to work continuously for 24 hours—was omitted from the copy provided to Fuchs. This omission was deliberate, as the intention was to question the workers listed in the protocol during an upcoming visit to Boryslav, without giving Fuchs or Meller, who had already been warned about this matter, the opportunity to influence the workers and pressure them into giving false testimony.

It is further noted that the complainant, Jan Zaręba, according to reports from other Boryslav workers, is regarded as a relatively intelligent man, conscious of his human dignity and determined to free himself, by any means, from the exploitation by the mine’s cashier and his overseers…

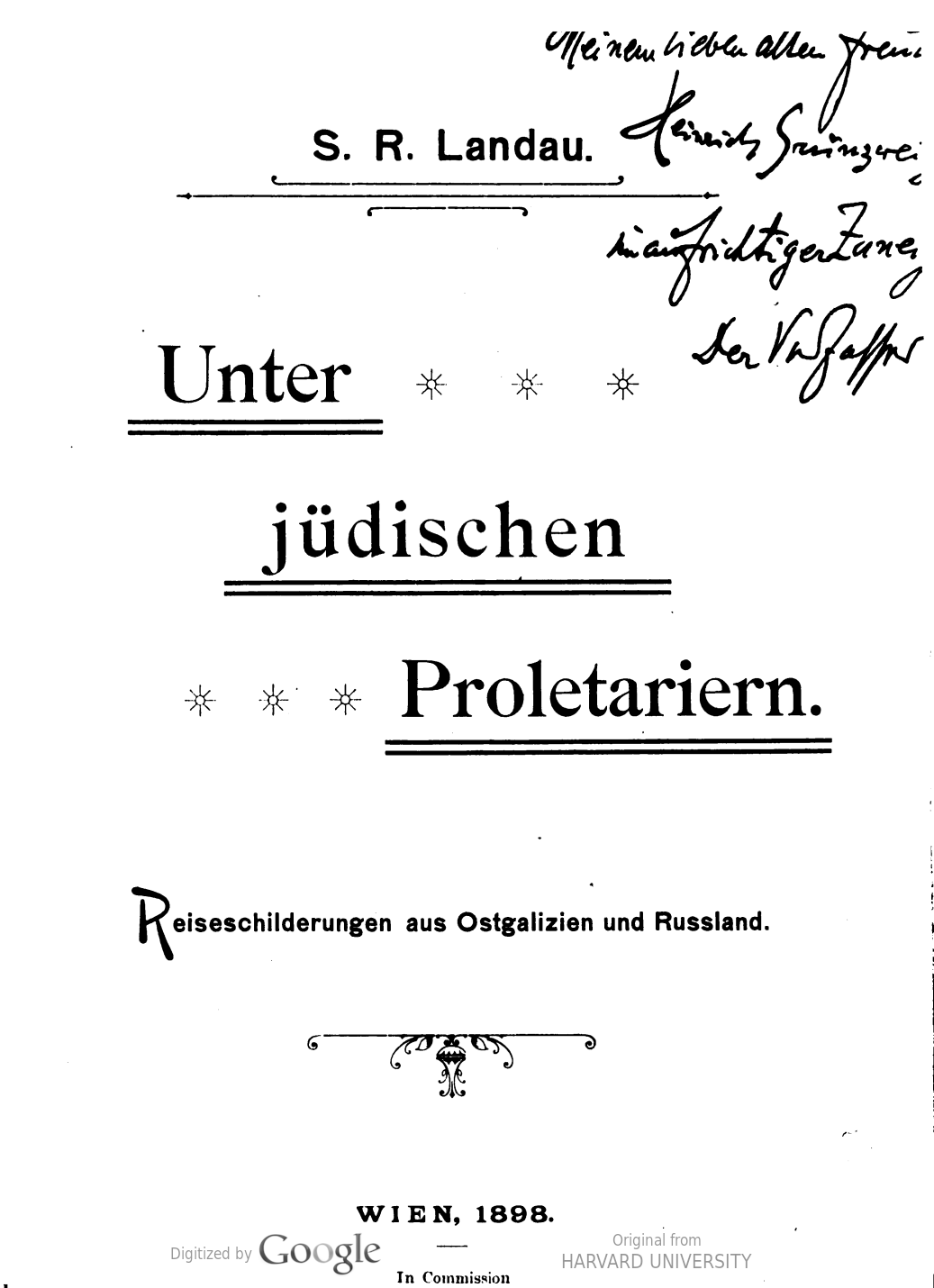

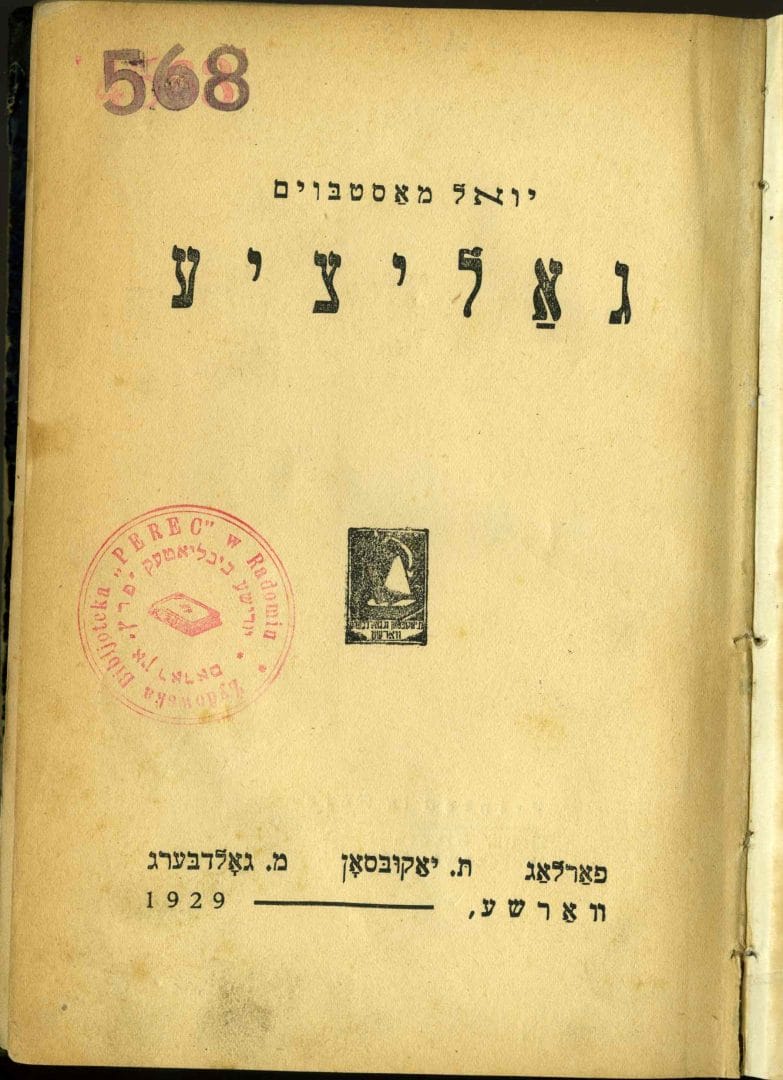

At the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries, oil workers in Boryslav formed a diverse and uneven group that included local Ukrainian peasants, Polish migrant workers from Western Galicia, Jews, and skilled workers from other countries. Some were seasonal labourers who came to work in the mines only when there was no field work in the villages where they permanently resided. Shared origins from the same locality or belonging to the same ethnic or religious group often took precedence over a sense of themselves as a professional group or class. In this respect, the industrial environment in Boryslav resembled the mining industry in new towns such as Yuzivka in south-eastern Ukraine. One feature that distinguished Boryslav was the presence of Jewish workers alongside Jewish entrepreneurs and intermediaries. Jewish workers became an argument for Zionist and socialist activists in favour of the idea that Jews could work “productively”—that is, engage not only in trade but also in physical labour. Yet they often remained “invisible” to Ukrainian or Polish observers. Job search strategies, the dynamics of relationships in the working environment and with mine owners, and the vague structure—after all, workers could also become small entrepreneurs—complicate their description and analysis within the framework of labour history.

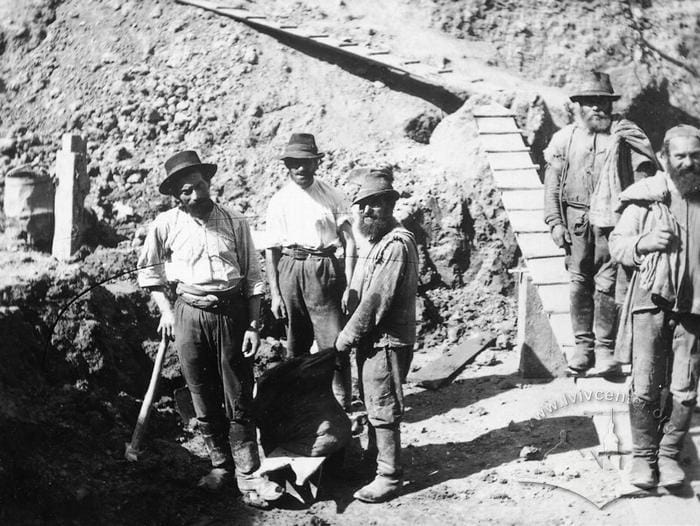

The documents in this collection present several perspectives on the workers of Boryslav: a protocol regarding a worker’s complaint, two reports from the late 19th century and 1928, and photographs from an oil entrepreneur’s album. Each of these sources relates, in some way, to the intersection of ethnic and professional categories, which remained divided throughout the history of the oil industry in Galicia. When we encounter the “voice” of workers—or, less often, female workers—it is always mediated by intellectuals or educated officials, who shape this voice, weaving it into their own narratives of control, modernisation, Zionism, or socialism. The texts are written in different languages—Polish, German, and Yiddish—but they do not reveal which language the Boryslav workers themselves actually spoke. The images of the workers similarly reflect this subjectivity, offering varying perceptions depending on authorship and the purpose of the publication: from capturing a worker’s function within an enterprise to presenting a more emotional portrayal of several workers as a single community.